On February 14, 2018, Annika and Mitch Dworet were waiting to pick up their two sons at their high school in Parkland, Florida, when they got a call from Alex, 15: He told his mother he was in the back of an ambulance—he had been shot.

Annika took off for the hospital where Alex was taken, with the immediate hope that since he had been able to call her, he wasn’t in dire straits; it turned out that a bullet had grazed his head. But as a crowd of parents quickly gathered at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, with word spreading that a number of students had been killed, Mitch, still at the high school, repeatedly called his older son: Nick wasn’t answering his cell. Where was he?

The Dworets wouldn’t get the news until 3 a.m., the last family taken into a private office by the FBI: Nick, captain of the swim team, with an athletic scholarship secured to the University of Indianapolis, who was so in love with his girlfriend he had exchanged homemade hearts with her on this Valentine’s Day—he was dead. Sixteen other students had also been murdered by a 19-year-old former Stoneman student in one of the worst mass shootings ever at a school in the United States.

In the days after Nick’s murder, the Dworets’ house was full of family, friends, and neighbors bringing them food. “Without that, I probably wouldn’t have gotten out of bed or taken a shower,” Mitch, 62, says.

Mitch was a longtime restaurant manager and a realtor; Annika, 52, a pediatric ER nurse. They had shared with both sons a passion for sports— running and biking—and Nick found a calling in swimming; he dreamed of representing Sweden, his mother’s native country, in the Olympics one day. It had been a close, active family, fractured in a way that was not only sudden but incomprehensible. And the trauma of their loss threatened to swallow them.

The Dworets needed to be alone, too, though being alone was possibly worse.

The family’s pain sometimes isolated them from each other. Mitch remembers, especially right after Nick’s death, “thinking about something and I’d just cry. And Annika’s not in the same place at that moment or vice versa. And it took us about three months to realize, wow, we have our son Alex in the other room who is in just as much trauma as we are.” Or more—Alex had been wounded, had lost his brother, and witnessed terrible violence happening to others.

The family soon got into therapy, which helped some, but for the better part of two years they had no real way of coping, and the level of trauma they were feeling was a dangerous place to be. Annika, describing the state of exhaustion, depression, and anxiety she was in, cuts to the chase: “To stay in that would be destructive, and I had to find something to get out of that, or I could stay in it forever. And that would be really bad.”

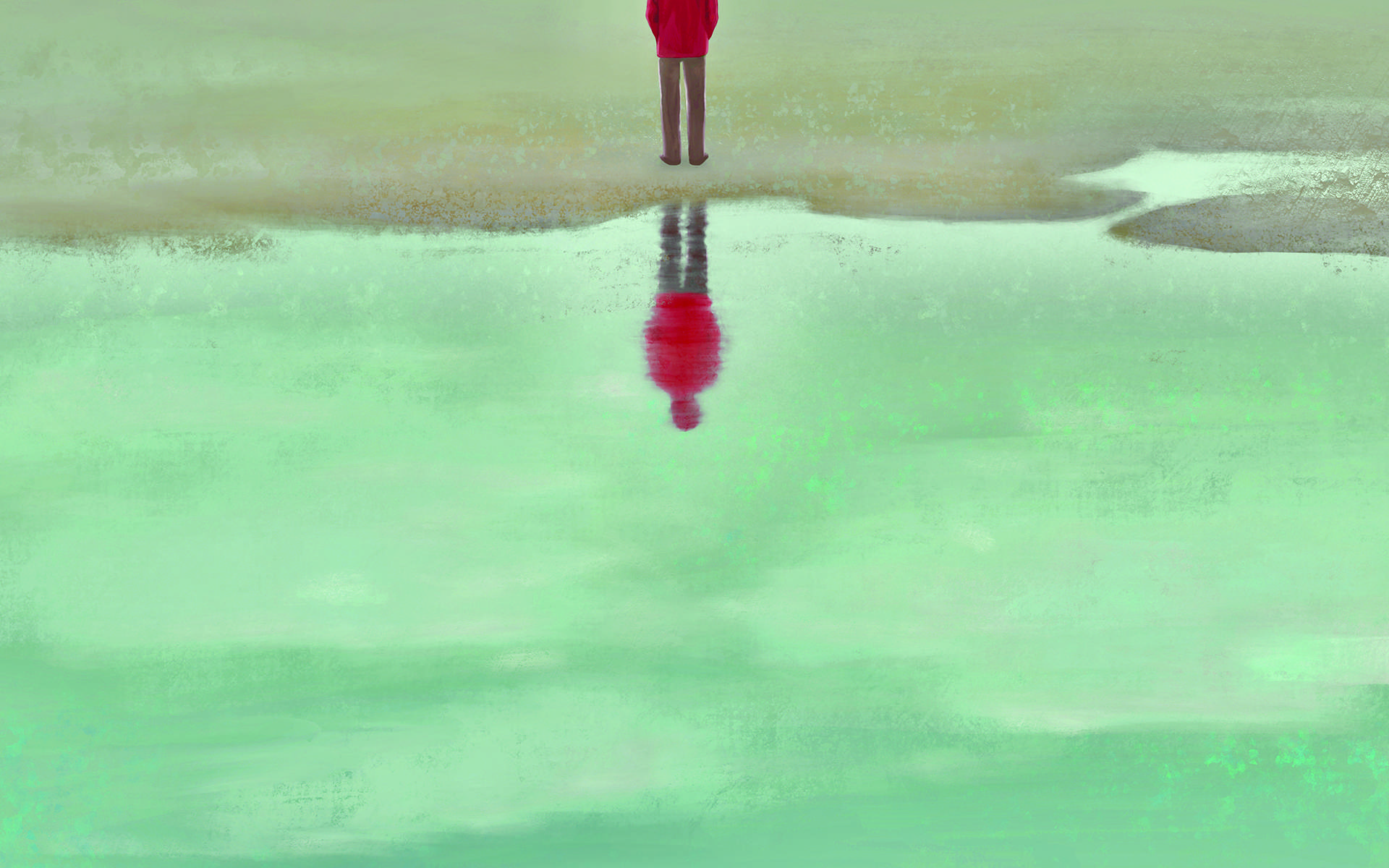

“You go down the rabbit hole of grief, and it’s very lonely,” says Mitch, who had gone into a vortex of his own scattered thinking after Nick’s murder: “It’s a feeling of desperation—I’m desperate to see my son again. I’m desperate to get back to moments of happiness that I used to have, but I can’t get it back because I can’t get Nick back. And then it goes in different avenues: Oh my God, what happened to Nick? The violence—the violence of what he went through. And I miss him and I…I won’t be able to ever hear his voice or see him again, and I won’t be able to experience a future. And I start thinking about what would have been, or what he would look like. He was just going to be 18.”

Mitch unraveled, again and again, into a place of deep despair. There seemed to be no way out.

The Journey Through Pain

In Chicago, Brenda Mitchell had been traveling a similar path of unremittent pain for more than a decade.

Brenda, 66, can speak calmly now about losing her son Kenneth, who was gunned down outside a bar in suburban Chicago in 2005. He was 31. “Never in a million years would I imagine Kenneth would be the one to die from an act of gun violence,” she wrote in an online piece for Moms Demand Action, which describes itself as “a grassroots movement of Americans fighting for public safety measures that can protect people from gun violence.”

Kenneth was the first grandchild in a close African-American family, a role model for his cousins and siblings. Kenneth had two young sons and a third on the way, and he was the family member, Brenda says, who would organize a barbecue if they had not gathered for some time. Kenneth was manager of a golf center in University Park, a Chicago suburb, and the weekend he was killed he was about to host a Super Bowl party. Kenneth had gone out the night before to a sports bar to play darts with friends.

As he was leaving the bar, an argument broke out between two men; he tried to intervene as a peacemaker, Brenda says. But a friend of one of the men went to his van, got a gun, and opened fire, killing Kenneth.

“A week earlier he had taken his brother to the airport for his third tour of duty in a conflict in the Middle East,” Brenda says. “And this tour was his last tour in Afghanistan, only to lose Kenneth a week later in a free country.”

The trauma of gun violence disproportionately impacts people of color, especially African-Americans, in the United States; homicide is the leading cause of death for Black males up to 44 years old. According to a CDC analysis, Black men and boys ages 15 to 34 accounted for 37% of gun homicides in 2019 in the United States, though that age group comprises just 2% of the country’s population.

For a long time after Kenneth’s murder, Brenda tried to carry on, denying her pain. Last spring, she spoke at a Zoom conference on how mindfulness can help people who have lost a loved one to gun violence. “I was in a doctor’s office and she was recommending that I don’t go back to work,” Brenda said, remembering how she felt a full decade after her son’s killing, “and I actually had on a new outfit to go to a new job. I had to realize that I was broken and I was fragile. And I stopped in that moment to realize that I no longer saw myself—I couldn’t see me anymore. Everybody talked about a new norm, but I didn’t know how to get there.”

I no longer saw myself—those are chilling words; Brenda had lost not just her son but something even more basic: who she was. She had raised her two young grandsons and was working a demanding job in human resources in health care while also serving as a pastor of her church. Her own health was at dire risk; Brenda’s blood pressure soared to 250 over 110. She took her doctor’s advice, going on disability instead of starting the new job.

But Brenda was still a long way from reclaiming her life—or herself.

Where Do You Store Your Trauma?

Trauma is a psychological, emotional response to a deeply disturbing or distressing experience or event. People who experience trauma may feel unsafe, with a reduced capacity for regulating their emotions and navigating relationships. Trauma can shake our sense of self and cause lasting harm to our ability to live a full life.

The good news is, healing from trauma is possible.

Fadel Zeidan is an associate professor of anesthesiology at the University of California San Diego. He wanted to better understand the efficacy of trauma-informed mindfulness—specifically, how mindfulness might relate to the trauma of losing a loved one to gun violence. In early 2021 he had an opportunity to conduct a study of gun violence victims as they went through an intensive eight-week course in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) training. Those taking part in the study would also become trainers themselves and the new trainers could then teach others to become trainers too. The research was ambitious and far-reaching.

Zeidan has been studying mindfulness for more than two decades; he wrote his undergraduate honors thesis at UNC Charlotte on how one 20-minute session of mindfulness meditation reduces anxiety. But back then, he didn’t see how it could be studied objectively or empirically, and Zeidan was advised by many professors not to go down that path. “The study of mindfulness was considered woo-woo at the time,” he says. “As scientists we were very aware of what happened with the Transcendental Meditation movement in the ’70s and how it’s important to not bias data based on one’s own subjective experience.”

Despite the academic risk, Zeidan was hooked. He published research on mindfulness in graduate school, and then brain imaging began bringing science into the field in a new way, or at least the possibility of it. Zeidan didn’t hesitate: His postdoc fellowship zeroed in on brain imaging and mindfulness, and he would publish the first paper on the meditating brain, in the Journal of Neuroscience.

A Palestinian refugee, Zeidan is passionate about examining the horror of gun violence in America and the role he thinks mindfulness could play in helping those who have lost loved ones. While many studies (besides Zeidan’s) on how mindfulness impacts the brain have been published in the past decade, no researcher has drilled down into how mindfulness might affect the life-altering state Mitch and Annika Dworet and Brenda Mitchell found themselves in, the trauma of loss on that level. The most relevant data we have, according to the University of Utah’s Eric Garland, who has published more papers on mindfulness than any other researcher, are studies on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In Zeidan’s new study, 22 participants from Survivors Empowered, a national organization serving as a resource for those who have suffered loss through gun violence, were trained for eight weeks in MBSR via Zoom (Brenda Mitchell was one of the 22). They experienced changes quickly at a scale that Zeidan found impressive: 37% reported reduced symptoms of trauma; 52% a reduction in symptoms of PTSD (“a 52% reduction in post-traumatic stress symptoms on the scale that we used is really profound and incredibly encouraging,” he says); 52% were less depressed; sleep disturbance was reduced by 26%; and overall life satisfaction improved by 16%. “Some participants were able to close their eyes and not see their kids or their lost loved ones,” Zeidan says. “That was really striking to me.”

At the same time, he cautions restraint. The results are preliminary, and it’s a very small, self-reporting study. Full-scale studies with control groups need to be done; changes to the physiology of mindfulness practitioners will be the home run of scientific corroboration. Still, Zeidan’s study has teased the possibilities; the Hemera Foundation granted $100,000 in fall 2021 for Zeidan’s laboratory to continue his work on how survivors of gun violence might benefit from mindfulness. And larger studies could measure what’s happening with the body, to find out whether the dramatic preliminary evidence of significant changes is confirmed.

One of the organizers of Zeidan’s study, Beth Mulligan, who is a long-time teacher of mindfulness, lays out how MBSR, the most widely taught mindfulness program in the world, can give direct help to people in the throes of trauma.

When the pull of the trauma threatens to take over, Mitch breathes. He listens. He stays with himself. He notices.

MBSR training starts, she says, by teaching the body scan. It’s not a relaxation technique, but a way to get tuned in to the sensations of one’s body, especially increased heart and respiratory rates, all the different ways we feel stress. “And we build on that resource of knowing the body,” Mulligan says, “so that when the fight or flight response hits, you recognize it much, much sooner.”

Triggers can come from anywhere: a car backfiring, or a shooting in another city on the news, or simply out of nowhere when one is sitting quietly on the couch and a flashback pops up—what Mitch Dworet calls going down the rabbit hole of reliving the trauma of Nick’s murder—and that’s when the practice of mindfulness can come into play.

“Because every time you relive what happened, your body responds like it’s happening now,” Mulligan says. “But you start to see that you have choices over what happens next.” She describes a quick route back to the present moment: Feel the sensations of breath, the rhythm of your chest going up and down, feel your feet on the ground, where your hands are, perhaps you look around the room and notice that the room is safe, that you have a roof over your head. Simplicity is the point here, in coming back from what’s threatening to overcome your mind. “And that calms down the whole nervous system.”

Seeing where the mind goes and coming back to the present moment, seeing where the mind goes and coming back—practicing that skill endlessly can make it possible to live with life-changing trauma.

Sharing the Practice So Others Can Heal

A little less than two years after Nick was killed, Mitch Dworet went to an event for the local community, an introduction to mindfulness conducted by two meditation teachers, Shelly Tygielski and Sharon Salzberg, in late November 2019; Jon Kabat-Zinn, the founder of MBSR, was also a teacher there.

Just being in public after the murder of Nick was hard—Mitch often found being around other people frightening, as if trouble loomed everywhere. And he had no idea if mindfulness could help. But something clicked there for him during a loving-kindness meditation: He felt calm. He felt safe, even in a roomful of people. Then Mitch went to one of Shelly’s Sunday morning meditations on the beach in nearby Hollywood; about 50 people were there, but, again, Mitch felt safe. He sat in the sand and let himself be guided in meditation, focusing on his breath. He listened to the ocean rolling in. “And I was very comfortable with that,” Mitch says. He had begun to discover a new tool.

Mitch mentions how Shelly “showed up for me”—he means it literally, in her warmth and friendship, but it’s also a sort of metaphor for connection to the moment, what mindfulness, with a great deal of practice, began to give Mitch: A way to be present, a way to show up to the here and now instead of going down the rabbit hole of past trauma.

Mitch mentions how Shelly “showed up for me”—he means it literally, in her warmth and friendship, but it’s also a sort of metaphor for connection to the moment, what mindfulness, with a great deal of practice, began to give Mitch: A way to be present, a way to show up to the here and now instead of going down the rabbit hole of past trauma.

Annika—who, like her husband, possesses an openness borne of deep sensitivy—started joining Mitch in the group meditation sessions at the beach, but the process was slower for her. “Every time I closed my eyes and went to that still place, I had such horrible, horrible thoughts in my mind that I had to stop,” she says. “It was much too overwhelming.” Mindfulness can take a great deal of practice— no matter where you’re starting from. Slowly, in small increments, it became useful for Annika too.

She would learn to bring mindfulness into ordinary life, to practice mindful eating, mindful walking, even taking mindful showers. She learned to stay within the moment, and within herself. Now she often goes to sleep with a guided meditation playing in her headphones. It’s mindfulness as a way of life: Out of the trauma the Dworets have suffered, the value of what the practice offers has emerged.

It would be absurd to think that they’ve found a way out of grief. The grief is permanent. They lost their son. Alex, now 18, lost his brother. The loss of Nick is part of who they are now. As Mitch puts it, “There’s not an end to this.”

Alex, Annika says, is doing OK, as he continues to see a trauma therapist. The practice of mindfulness, he’s decided, is not for him. Last fall he started training to become a mechanic.

Learning to be present in the moment, through mindfulness, hashelped Mitch as a father, he says: “I wanted to show up for Alex and be a better listener instead of thinking forward or back.” It happens in small, typical family moments, he says, just hanging out on the couch, talking about, say, cars—Alex’s passion. Mitch has learned to slow himself down and listen rather than telling Alex what to do or how to think. Instead, he tries to hear what his son is saying.

It’s a day-by-day practice.

One morning late last summer, Mitch Dworet got up early, as the sun was just rising, before it was hot in Parkland, and went out into his yard. He sat and meditated, resting his attention on his breath, on the sounds of birds beginning to sing in the dawn light. As he sometimes does now, Mitch placed his attention on an intention for the day: That day, it was patience. He sometimes feels angry over how long it has taken to bring Nick’s killer to justice. But he doesn’t want to go down that rabbit hole, to live in that rage, to go back to the chaotic emotional hell he had so much trouble coping with in the aftermath of his son’s murder.

Instead, when the pull of the trauma threatens to take over, Mitch breathes. He listens. He stays with himself. He notices. And with patience. With breath. He knows he’ll keep tapping into that simple way back to the moment, and to himself, at vulnerable times throughout the day, and during every day to come.

Choose to Live

For Brenda Mitchell, mindfulness meditation opened the door she had closed on herself after her son Kenneth’s murder.

In 2019, Brenda would go to a big mindfulness retreat near Boston, organized by Shelly Tygielski and Sharon Salzberg, that included survivors and family members of victims from shootings in ten cities. “Let me just tell you, it was five days with no outside contact, no phone, no TV, no nothing,” Brenda remembers, laughing now at the sacrifice she thought she was making. “The only person I could listen to was me.”

“I had to create a new narrative for myself and choose to live.”

Brenda Mitchell

What she learned at the retreat was both simple and profound. When she feels vulnerable, or, as she describes it, “when I find myself in a position, I pause and I breathe. I take a vacation with myself, for three minutes, whatever it takes me to just bring myself back and center myself. Mentally, I’m focused on absolutely nothing. I let my head go back and it just takes me to a place.”

After confronting her pain in therapy, Brenda says meditation allows her to remain with herself when grief threatens to derail her. It can seem, on first blush, to be a contradiction: The recognition of her pain over Kenneth’s murder, finally feeling her pain, led to her healing; the denial of it was literally killing her.

As she says, “I kept trying to get back to normal and there’s no such thing as normal for me. And so what I learned in the process is that I had to create a new narrative for myself and choose to live.”

Mindfulness allowed Brenda to heal “from the inside out as opposed to the outside in” she says. “Mindfulness helped me see me again. It told me that my brain belonged to me.

read more

Healing the Trauma of Gun Violence

How one couple who lost their daughter to gun violence is using mindfulness training to help themselves and others move forward.

Read More

A Trauma-Informed Meditation to Uncover the Potential for Healing

MBSR teacher John Taylor offers a five-step meditation for finding a greater sense of peace and freedom after trauma.

Read More

Grief is Love with No Place to Go

Parkland parent Fred Guttenberg’s book Find the Helpers implores us to find hope and purpose in the face of loss.

Read More

Healing in the Deep Ocean of Grief

Grief can hold our heads beneath the waves, but, as Bryan Welch writes, its tides can also open us to compassion for ourselves and others, showing us the value of a broken heart.

Read More