Summary

Modern life’s constant stressors, from notifications to global challenges, can push us into crisis mode, risking burnout. This article, aligned with Mindful’s mission of accessible, science-backed mindfulness, offers compassionate, practical steps to manage stress with self-kindness, fostering calm and resilience in an inclusive, secular way.

Understanding Stress

Hans Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome outlines 3 stages

- Alarm (fight, flight, freeze)

- Resistance (adapting to stressors)

- Exhaustion (burnout from chronic stress). Chronic stressors, like work or social media, trigger physiological and psychological reactions, impacting sleep, health, and focus.

Signs of Burnout

Watch for emotional exhaustion (feeling drained), depersonalization (cynical attitudes), and low personal accomplishment (feeling incompetent). Symptoms like irritability, poor sleep, or physical aches signal the need for action, possibly with professional support.

Strategies to Manage Stress:

- List Stressors: Identify acute/chronic and internal/external stressors to externalize and manage them.

- Assess Changeability: Reframe unchangeable stressors as learning opportunities or shift your perspective.

- Take Small Steps: Address stressors with small, positive actions, setting clear start and end times.

- Build Support: Leverage internal strengths and external resources like friends or activities for support.

- Track Uplifting Moments: Note activities that nourish you, like mindful breathing or small rituals, to build resilience.

- Embrace Change: Recognize that stressors are temporary, creating space for calm.

Web of Reactivity Exercise: Log thoughts, emotions, sensations, and impulses during stress. Pause to breathe, observe, or act mindfully to disrupt stress spirals, fostering clarity and ease.

These steps empower everyone to navigate stress with curiosity and compassion, promoting well-being without relying on spiritual or unscientific approaches.

Modern life seems to offer endless moments of stress. Perhaps you wake up in the morning to the sound of your phone’s alarm blaring, sending a hit of adrenaline through your system. Then, you might get another hit as you scroll through your news feed and learn about the latest global or local disaster. These days, it can feel as if there are threats everywhere, real or imagined, and the body and mind react accordingly in any number of ways. Your heart may speed up or you may feel sweaty, hyperfocused, or simply avoid whatever happens to be unpleasant in the moment.

We may have thought that technology would make our lives easier. But instead we are inundated with packets of data, much of it irrelevant. Facebook tells us what our long-lost friends are doing on vacation. Google reminds us of a holiday potluck we are supposed to attend. We can endorse professionals on LinkedIn so they will endorse us. And Twitter—well, who knows what’s going on with Twitter? Meanwhile, a device on our wrist reports that last night, we had 45 minutes of “restless sleep.” Email has become, in the words of a friend of mine, “a To-Do list that you didn’t create.” And the plethora of apps at your fingertips that help you, say, navigate IKEA more effectively provide minimal payoff.

Our inability to step out of the information flow—such as at work where we may be required to stay plugged in or can’t seem to get away physically or psychologically from our phones at any time—has a direct effect on our health and well-being. Namely, and not surprisingly to many of us, an increase in stress reactivity.

The Three Stages of Stress

There are many definitions of stress, and one is from the original father of stress research, Hans Selye: the nonspecific adaptation response of the body to any demand or problem. He described a process of how we respond to stress called the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS). It consists of three stages: Alarm, Resistance, and

Exhaustion.

- Alarm involves a number of physiological reactions—hormonal, neurological, cardiovascular, and so on—and psychological reactions, as we move into a fight, flight, or freeze response for survival.

- Resistance may be viewed as the physiological and psychological attempt to adapt to and overcome the effects of the stressor. This is all well and good if the stressor resolves. If not, the stress hormone cortisol can continue to be produced, resulting in poor sleep, increased illness, anxiety, or poor cognitive functioning.

- Exhaustion may follow when a stressor becomes chronic, either from ongoing exposure or ineffectual and repeated attempts to deal with it. We become overwhelmed.

The Warning Signs of Burnout

Fortunately, most of us now live without the threat of saber-toothed tigers—but we instead face long commutes, harsh emails, an unforgiving economy, climate change, COVID-19, and constant reminders via social media about how well others are doing in comparison to ourselves. These stressors result in the same internal reactions as when we are confronted with something life-threatening.

When we are faced with a stressor, regardless of whether it is positive or negative, it involves a change to which we must adjust: the new baby, job, relationship, death, or sickness, to name a few. Stress itself may not be the issue but rather how chronic and severe it tends to be, our relationship to it, and what we do when stress shows up. Humans must necessarily adapt psychologically, socially, biologically, and environmentally. And we are nothing if not problem solvers. But even too much problem-solving can result in burnout.

And while burnout may feel inevitable for many of us in our current context, there are symptoms of burnout to watch for, according to The Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual, used by researchers as a measure for long-term occupational stress.

You may experience emotional exhaustion—a feeling of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by work or life. This is common for people in the helping professions when they reach a point where they feel no longer able to give of themselves.

Our inability to step out of the information flow has a direct effect on our health and well-being.

Depersonalization is characterized by a negative, cynical attitude, or treating others as objects. We can begin to see others as deserving of their problems. This view is particularly tied to emotional exhaustion.

The third symptom to watch for is a sense of low personal accomplishment, marked by feelings of incompetence, inefficiency, and inadequacy, in which you feel unhappy and dissatisfied with yourself and your performance. This can lead to “learned helplessness” and “chronic bitterness.”

You may notice that you feel disenchanted, that you struggle to get out of bed, or to focus once you’re at work. You may have a short fuse with colleagues and clients, feel sapped of energy to follow through on projects or concentrate on one task. Your sleep and appetite may be affected. You may use substances to avoid feelings, or experience physical symptoms like headaches and backaches. Sometimes it can be difficult to differentiate burnout from depression, so getting help from a mental health professional may be in order.

All of this of course may affect both your work and personal life, making you miserable, affecting relationships, and decreasing productivity.

Here Are Small Steps to Less Stress

Regardless of the cause of your stress, there are a number of steps you can take to manage it. Begin by bringing kind attention to your experience, and extend compassion to yourself as you tend to your stress. And then consider these strategies:

1) Make a list of your personal stressors.

Susan Woods, a well-known mindfulness teacher, suggests we think of them in terms of those that are acute or chronic and internal or external. Realize that these categories may overlap. One can have an acute or chronic problem. For example, an exacerbation of ongoing back pain due to an injury, or a stressor that may be both external and internal; an example would be a stomach pain due to a conflict you’re having with a spouse. Writing them down can help you deconstruct them, making them less overwhelming and more manageable by externalizing them. We don’t have to be them; we can simply have them. And remember: Stressors are finite.

2) Determine which stressors you can change and which ones you can’t.

Once you identify a stressor that can’t be changed, ask yourself how you might bring a change in attitude or perspective to it. Can you see it differently? Can you accept it? Can a problem become a learning opportunity or a challenge to overcome? Can a task become something that gives you a sense of accomplishment?

3) Do one small thing.

Can you come up with a small, manageable way of beginning to address the stressor or your reaction? Make sure the action you are going to take is stated in positive and concrete terms—think about what you are going to do rather than what you won’t do. Set a time to start and to finish. Don’t try to do too much. Remember, small steps are key.

4) Build a support network.

Can you identify your inner and outer resources for getting support and managing stress? For example, if you are feeling burned out from work, consider making a list of your internal resources. What are your strengths? Make a list of people, places, activities, or things that could be external supports. Maybe you need an exercise buddy, a friend to vent to regularly, or do an online search for a meetup that might fill a need.

5) Monitor and write down those times when you feel even a little bit better.

How can we build and protect our inner resources, our internal supports? Monitoring what uplifts you can reveal clues as to what your inner resources are. Maybe there are small activities you find nourishing that you’ve stopped doing, like that cappuccino and podcast you used to enjoy first thing in the morning, or simply taking a few deep breaths when feeling overwhelmed. Remember: The breath is always with you. Start small and schedule! Trying to do too much will likely result in you not doing anything except wanting to pull the covers over your head in a state of overwhelm. Above all, try to be kind to yourself.

6) Finally, don’t forget that everything changes.

Nothing lasts. And since change is inevitable, we can remind ourselves of this and get a little breathing room if nothing else until the stress storm passes.

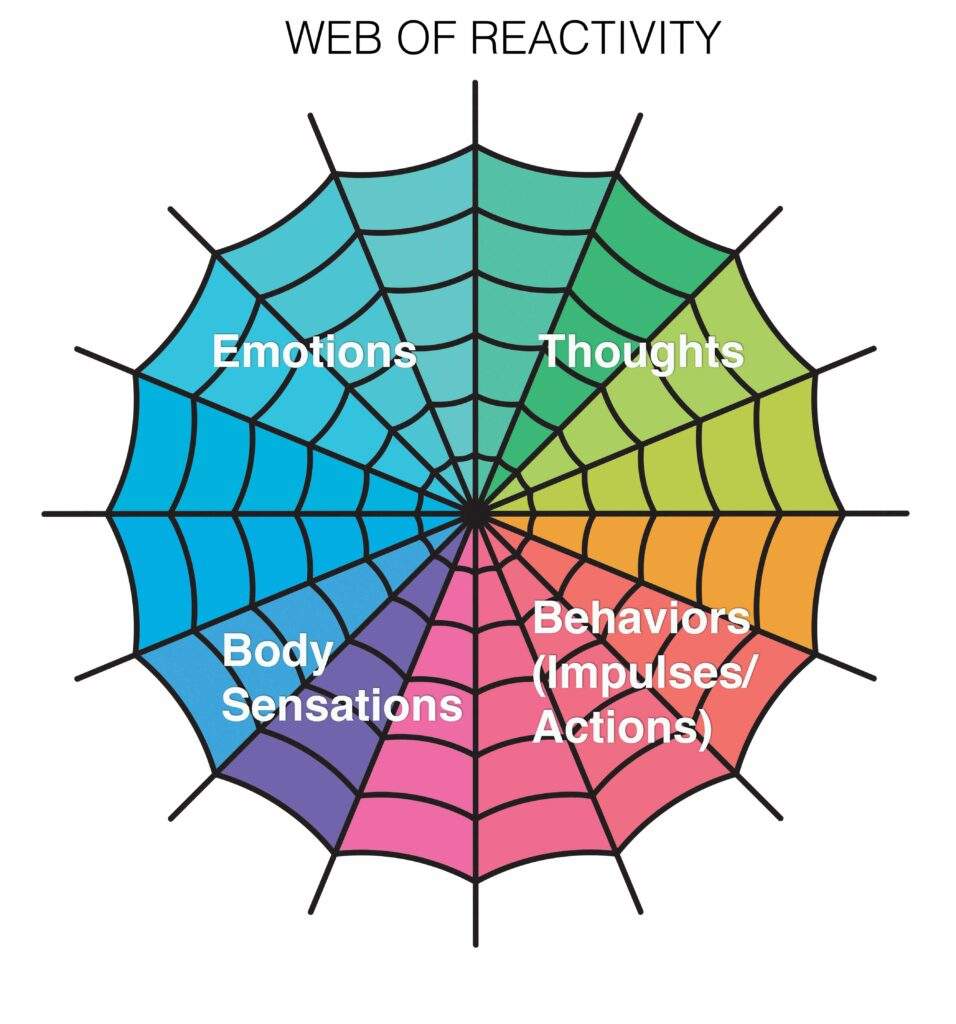

Caught in the Web

When we’re stressed, we often click into automatic and habitual reactions to what’s stressing us. Mary Elliott and Evan Collins created an exercise using the Web of Reactivity to help us become more mindful of our triggers—and our thoughts, emotions, body sensations, behaviors, and impulses to act—when we are stressed. Try this practical approach:

- Write down your thoughts, emotions, body sensations, behaviors, and impulses to act during stressful moments. Describe the situation (where, when, who, what). List your initial “automatic” thoughts. Take note of your emotions/moods in one word, or as many as you like. List where you felt these emotions in your body. List your actions/impulse to act.

- After you make a list, ask yourself where and how you might bring mindfulness to these reactions. Perhaps stopping and taking a breath, bringing attention to body sensations, or bringing curiosity to the experience may disrupt the tendency to cascade into a stress spiral. Also, consider whether the situation needs addressing through action, and if yes, how.

read more

A Simple Inquiry Practice to Unwind from Stress

The act of questioning the thoughts that shape our reality (especially when they create stress, anger, or frustration) opens the door to living a life with more compassion, ease, and openness to new possibilities. Read More

This Kind of Movement Can Be the Key to Healing Burnout

Coping with any degree of burnout can leave us feeling stuck. Sometimes, what we need to begin healing and to rediscover joy is to (literally) move our way through it. Read More