The human body is a complex machine, working ceaselessly—often without our conscious effort—to maintain balance and support life. Our hearts, lungs, kidneys, intestines, liver, skin, brain, every organ in the body, are in constant flux and activity from the moment we are born. In short, the human body is a miracle.

In recent years, a topic of growing importance is understanding what genetic mechanisms underlie psychological and physical health. This is critical in helping us understand whether mind-body interventions (MBIs) such as mindfulness can reverse the molecular effects of chronic stress, and whether MBIs can contribute to disease prevention.

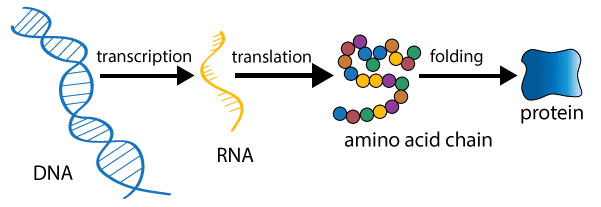

Scientists have recently taken a step further in studying the biological mechanisms of MBIs by analyzing gene expression—a humble process that happens inside each and every one of our cells, by which DNA sequences are transcribed and translated into proteins. Researchers are asking questions like: Can MBIs like meditation influence our gene expression? Does this make molecular changes to our physical health? If yes, what are these molecular changes specifically and how do they benefit us?

This past summer, a meta-analysis in Frontiers of Immunology looked at changes in gene expression induced by meditation and related practices. The authors, from Coventry University’s Brain, Belief and Behaviour Lab and Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour, examined 18 different gene-expression studies. These included MBI techniques spanning mindfulness, yoga, Tai Chi, Qigong, relaxation response, and breath regulation. The verdict was clear: Yes, meditation practice is indeed capable of reversing the effects of chronic stress, down to the level of our genes. (Yet, it should be noted that this research is still in its infancy and mindfulness is not a replacement for medicine nor will your mindfulness practice prevent disease.) Before we look at the study results, let’s take a brief look at the science of gene expression.

What is Gene expression?

Gene expression is the process by which DNA sequences are “expressed” into proteins. Different sections of DNA code for different amino-acids (the building blocks of proteins). These DNA sections are essentially copied and translated into proteins, which are needed for cellular functioning.

How quickly or slowly a DNA sequence gets copied and translated into its corresponding protein depends on something called the Transcription Factor. Some transcription factors drive up the rate of DNA transcription—they increase the process of gene expression. Other transcription factors may slow down the rate of DNA transcription—they decrease the rate of gene expression.

How chronic stress + unregulated gene expression = disease

In the complex world of gene expression, there are many things that can slow down or speed up the rate of DNA sequences being translated into proteins. Let’s take a simple example: Stress. Many of us have heard of the ‘fight or flight’ response, which is triggered by stressful or threatening events. When this happens, adrenaline and noradrenaline is secreted in our bodies. This increases the production of transcription factors that ramp up gene expression of pro-inflammatory DNA, thereby initiating inflammation in different parts of our bodies.

In the example of stress, the transcription factor that causes inflammation has a fancy name: Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NF-kB). Incidentally, scientists are also very interested in the NF-kB when it comes to understanding how mindfulness, yoga and other MBIs can decrease inflammation, and possibly reduce the risk of certain diseases

So, now, we are beginning to draw the map that depicts the relationship between psychological adversities, gene expression and disease risk, and pinpoint exactly where mindfulness practices are working to alleviate our mental and physical symptoms

Stress and inflammation are actually adaptive processes that have evolved to protect us from threatening or challenging events. When stress is very severe, or when it never stops and we don’t have good coping mechanisms, it becomes a health risk. Chronic stress not only affects our brain by altering connectivity and function, but also affects us on a genetic level. Scientists call this genetic change CTRA (conserved transcriptional response to adversity), which is another fancy way of describing “the inability to recover from a stressful event because it was too prolonged or too intense, and has now led to chronic inflammation.”

CTRA is commonly observed in people exposed to different types of adversaries, such as bereavement, cancer diagnosis, trauma, and even low socioeconomic status. CTRA causes chronic inflammation, which increases the risk for some types of cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, asthma, arthritis, cardiovascular diseases and psychiatric disorders (e.g. depression, PTSD). CTRA also lowers the body’s antiviral and antibody-related functions, and increases susceptibility to some viral infections. In sum, when we add chronic stress and inflammation together, there is a high risk of inflammation-related disease, infection, accelerated biological aging and early mortality.

MBIs as regulators of healthy gene expression (or: meditation as a regulator of the regulators)

In the large meta-analysis mentioned above, where they looked at 18 different DNA studies to find the key link between meditation practices and changes in gene expression, they found exactly this: a consistent and persisting result whereby 81% of the studies found that MBIs can reduce the levels of NFKB, therefore reversing the effects of gene expression of inflammation caused by chronic stress. MBIs in these studies included mindfulness, yoga, Tai Chi, Qigong, relaxation response and breath regulation. Some of these practices were physical and others sedentary. The studies also used different experimental designs, targeted different age-groups as well as different populations (including patients with irritable bowel syndrome, late-life insomnia, breast cancer or fatigue, and caregivers of Alzheimer’s or dementia patients).

So, now, we are beginning to draw the map that depicts the relationship between psychological adversities, gene expression and disease risk, and pinpoint exactly where mindfulness practices are working to alleviate our mental and physical symptoms—on an emotional and feeling level, on a brain and cognitive level, and on a genetic, molecular and immune system level.

As our wealth of psychological and biological knowledge about mindfulness practices increase, these help us understand the mechanisms at work. With time and practice we may become more attuned to the needs of our physical and mental wellbeing, and trusting that these practices can offer benefit in a deep way, down to the level of our DNA.