It was a lovely day in Berkeley when Gibor Basri decided to clean out the flowerpots on his second floor balcony, which overlooks a quiet tree-lined street not far from the University of California, where Basri works. Suddenly, two police cars pulled up, and a knot of officers ran into his yard, guns drawn and pointed. When Basri’s wife Jessica opened the door, they said they would rush her to safety because a “hot prowl”—a burglary in action—was in progress. She looked up. “Oh, that’s my husband.”

An astrophysicist, Gibor Basri claims Jamaican and Iraqi heritage and has dark skin. Jessica Broitman, who works as a psychoanalyst, is white. The two have been married for more than 40 years, have a grown son, and chose Berkeley as their home partly because of its reputation for diversity and a liberal attitude. But when someone driving by spotted a dark-skinned man on a porch in a good neighborhood, bias reared its ugly head. They called 911.

The police were quite embarrassed and apologetic, says Jessica. But they had been alerted that something strange was going on. “Yeah,” she shot back, “Something strange was happening, all right. It’s very unusual when my husband does any household chores. Really!”

“We are social creatures and need to be in relationship with others. Yet we find ways to deny our interconnectedness and marginalize each other. ”

john a. powell, researcher and law professor at the University of California, Berkeley

“A lot of people think about black teens and poor black people as victims of bias, but it’s everywhere,” says Basri. Ironically, in addition to his work as a professor, Basri is also the Vice Chancellor for Equity and Inclusion at the University of California, Berkeley, where one of his goals has been to increase the number of African-American students and faculty at the university and to make the campus a more welcoming place for them. “It is hard for someone who has not experienced a sense of pervasive negative stereotyping based on appearance alone to appreciate how incredibly wearing it can be,” says Basri.

And of course it gets worse. A nine-month stretch from late 2014 to mid-2015 saw the following events: the police shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri; the police choking death of Eric Garner on Staten Island; the death of Freddie Gray following harsh treatment while in police custody and the subsequent rioting that rocked Baltimore; and the video showing white fraternity members from The University of Oklahoma singing a racist chant on a school bus. In light of these, bias has become a critically important topic. In unprecedented remarks following the first two incidents and the ensuing protests, FBI Director James B. Comey acknowledged the “widespread existence of unconscious bias.” He said, “There is a disconnect between police agencies and many citizens—predominantly in communities of color. We simply must find ways to see each other more clearly.”

Whether it’s called unconscious bias, implicit bias, or “gut instinct,” bias influences the way every one of us sees and treats other people every day. It’s well-documented that gender equality in the workplace is deeply affected by bias. It’s what makes the world of scientific research and the tech industry run on man power. It’s one reason why orchestras used to be overwhelmingly male.

“We are social creatures and need to be in relationship with others,” says john a. powell, a law professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and a prominent researcher on race and human society. “Yet we have ways of denying our interconnectedness, different ways of marginalizing each other. A lot of times we do things we aren’t consciously aware of. It causes suffering all around,” adds powell, author of Racing to Justice. “Perhaps most damaging of all, bias can be internalized and make the subjects feel and perform as if the biases about them are true, both on tests and in the workplace, studies by Claude Steele have shown. It’s what he calls ‘stereotype threat.’”

Part of Our Makeup

Though bias seems like bad news all around, it’s a basic human trait. It’s part of our wiring for survival, explains psychiatrist and professor Daniel Siegel, codirector of the UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center. Bias helped early humans evaluate strangers quickly and determine who belonged in the cave and who didn’t. Those who made the right call went on to survive and reproduce, and so the trait was passed along. A cave dweller who guessed wrong might be killed.

“The human brain has been called an ‘anticipation machine,’” says Siegel. “It learns from the past to anticipate the future. Past experiences become perceptual filters that shape how you actually see or hear or understand what’s going on in the present moment.” Often this goes on beneath awareness.

“Some would say you are on automatic, you don’t do this on purpose,” says Siegel. “But at its farthest reach, bias may lead humans to systematically destroy people in the outgroup.” The Holocaust and other genocides reveal this extreme, says Siegel, when the compassion circuitry turns off. Bias can be reinforced by what Siegel calls “priming.” If the fear of death is present, we are primed to treat people in the outgroup with more hostility, people in our ingroup with more kindness. The point is not to get rid of bias altogether—an impossible mission—but to get to know what biases we hold, acknowledge the damaging aspects, and learn to see, and do, things differently. Sometimes there is a practical fix. Once a bias in favor of male musicians was identified, for instance, some orchestras solved the problem by having musicians audition behind a screen, so all that was known of them was the sound coming from their instruments.

In other cases, getting beyond bias—as much as we can—involves getting acquainted with what’s inside our brains. “Mindfulness in general allows a person to become more aware of what is arising, and to embrace it for what it is,” says Siegel. “It’s an excellent strategy for recognizing and softening the harmful effects of unconscious bias—that and learning to be at ease with uncertainty. “For the human brain, being uncertain can often be interpreted as danger,” says Siegel. “With mindfulness training, the brain can learn to rest in uncertainty without freaking out.”

At a recent conference on bringing mindfulness into schools at the University of California, San Diego, a systems change consultant who focuses on equity issues, Sheryl Petty, formerly of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, talked about how ingrained habits of bias can be in societies. She went on to say how as a meditation practitioner she appreciates how mindfulness can help us get past minimizing differences to accepting, adapting to, and integrating differences into our life and worldview (referring to stages on intercultural development models developed by Milton Bennett and Mitchell Hammer). But, she pointed out, there’s lots of work to be done. The people who have specialized in equity issues and diversity training over many decades have deepened our understanding of the historical, systemic factors that cause us to treat people unequally. But they “often may not know or say much about inner work and awareness practices, like mindfulness, and their role in systemic change.” Conversely, mindfulness teachers focusing on bias are not as steeped as they could be in an understanding of the systemic factors and might gloss them over. It would be great, she suggests, if these two groups started talking to each other.

We Do Not Know

Breaking through bias is possible when we truly open ourselves to someone else’s experience, says Vinny Ferraro, who runs mindfulness programs for youth and adults. Ferraro, who looks you in the eye, talks straight, and radiates compassion, grew up on the streets selling drugs. His father was incarcerated, his mother died young, and he himself was locked up and suffered from addiction before reversing his trajectory with the help of meditation. Now both a practitioner and highly respected teacher of mindfulness, Ferraro says, “The beginning of the conversation is if we can imagine at least for a minute that we do not know what is going on for other people, to suspend our belief that our truth is the only/whole truth, and to realize that all beings see through a lens of their own conditioning. Or, as the saying goes, ‘The only way illusion works is if we mistake it for reality.’”

“If we all got real, basically we would all fall in love with each other. I have seen that time and time again.”

Vinny Ferraro, longtime meditator and senior trainer with Mindful Schools

In 2001, Ferraro started working with a groundbreaking program called Challenge Day in Oakland, California, public schools. The event gathered high school students together and had them form small groups, with kids they didn’t usually hang out with. In an exercise called “If You Really Knew Me,” all were encouraged to share one true thing about themselves with the group. Once kids opened up and began to really see each other, feel each other’s experiences, the walls came down, says Ferraro. “If we all got real, basically we would all fall in love with each other. I have seen that time and time again,” he says softly, emotion rising in his voice. “If you get real with kids, they get real right back.” Ferraro has worked with more than 100,000 young people, including incarcerated youth. Today he is a meditation teacher with Against the Stream in San Francisco and a senior trainer at Mindful Schools, a nonprofit where instruction in mindfulness extends not just to at-risk youth, but to the adults who work with them—teachers, correction officers, social workers, parents.

“We should all be educating ourselves and waking up to the places we’ve gone to sleep so that the weight of our conditioning doesn’t land on the people it has always landed on,” says Ferraro. “One guy who experienced bias said it was like a thousand little paper cuts, all the time. As a straight white man, I can do what I can to reflect on this. The problem with waking up the world is that people don’t know they are sleeping! Mindfulness makes it possible to wake up.”

And after that? “Just see if you can approach every moment with kindness. Know what that does? It allows you to live in a kind world!”

“Compassion to ourselves, to everyone around us, that’s a core part of mindfulness training,” says Janice Marturano, a former Vice President and deputy general counsel for General Mills. Long known for the manufacture of Cheerios and other quintessential American products, the company is now known for introducing yoga mats and mindfulness to its Minneapolis headquarters. That began after Marturano discovered the connection between mindfulness meditation and leadership development for herself and benefitted so much that she decided to share the discovery with her coworkers. Today, General Mills has a meditation room as do a growing number of other US companies.

Nearly five years ago, Marturano left General Mills and moved home to New Jersey to found the Institute for Mindful Leadership, wrote a book called Finding the Space to Lead, and now brings mindfulness to organizations all over the world. Working with implicit bias is one focus of Big City Pause, a one-day workshop the institute inaugurated in May in New York City. “We all need to be able to work with people of different experiences,” says Marturano. In her early days as a young lawyer in a New York law firm, she recalls, “I encountered male partners who simply refused to work with women associates.” Today her aim goes beyond ideas of gender and racial equality. “What we need for our world and for our families is to be able to notice our unconscious bias,” says Marturano, “to be able to work with people of different experiences—not only to work with, but to embrace different experiences. It’s about opening up to the richness of being a citizen of the world,” she says. “We have to start with the idea that there is one planet and one human race and all the rest is insignificant.”

Color Insight

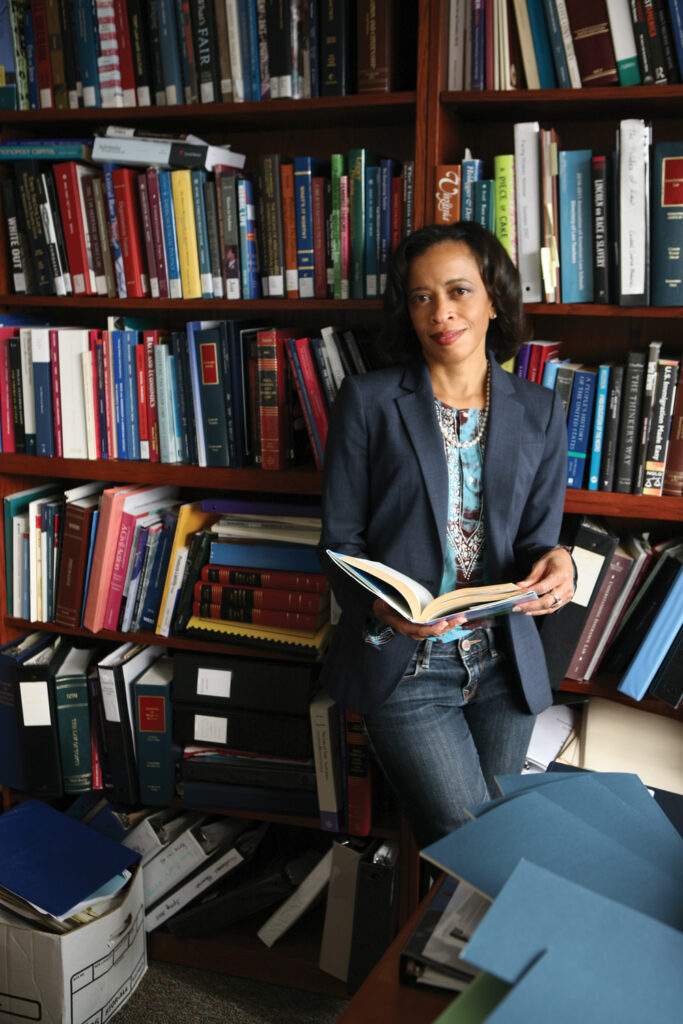

“Bias cuts off opportunities for people. If we are concerned about justice, we have to be concerned about bias,” says Rhonda Magee. For 17 years, she has taught law, including a number of classes about race and the law, at the University of San Francisco. “I am an African-American woman,” says Magee, “and there’s a way in which we never really know how we are being perceived by others in the world. Race-related bias has been a specific challenge to our legal system. And if bias is happening in the criminal area and in law, it’s happening anywhere and everywhere. I’m excited about the ways mindfulness practice can minimize bias.”

Rhonda Magee has taught law for 17 years. The issue of bias, she says, is inextricably linked to the issue of justice. As an African-American woman and longtime meditator, she has experienced discrimination firsthand, and has felt the positive affects of mindfulness on her ability to cope with bias. Photograph by Todd Rafalovich

Magee’s own longtime practice of mindfulness has helped her cope with the bias that affects her, both as a woman and a member of a racial minority. She tells of showing up in casual clothes one Saturday at a car dealership to buy a car, only to be roundly ignored by all the sales people, as well as by the manager; or of walking through a downtown store trailed by security people. “For those of us who are impacted by our race and our gender, these things have a cumulative effect, partly psychological, partly material and economic, she says. “Yet I am sure if you asked many of these sales people, ‘Do you have a bias against black women?’ they would say, ‘Of course not.’

“I think it is a really hard issue,” Magee admits, “But I feel heartened that we are talking about this more and people’s awareness is being raised.” Mindfulness reduces how we automatically process things, she says, and creates more spaciousness in the way we receive information. “In my teaching I have been basically trying to raise law students’ awareness of the ways race can infect the justice system and ways by which we try to seek justice. I think there is a specific need to incorporate mindfulness in a way that moves from color-blindness to what I call ‘color insight,’ which is an ongoing awareness of the many ways that race, color, and culture impact us in our interactions with others.” Magee grounds her teachings about race and law in mindfulness-based practices that help people develop “color insight.”

The practice of mindfulness can open our hearts, says Magee. “The piece I have been practicing with is to infuse this all with deep compassion for ourselves and others.”

Photograph by Mark Mahaney

All the technology in the world—cameras on police officers, etc.—won’t help until we work with police officers themselves.”

Richard Goerling, lieutenant with the Hillsboro Police Department in Oregon

Compassion for oneself and others is also on police officer Richard Goerling’s mind. Eight years ago, Goerling, a veteran cop ahead of the curve, began a personal mindfulness practice—to relieve stress, and get to know himself better. “It really became this deep introspective journey,” says Goerling, a lieutenant with the Hillsboro Police Department in Oregon. “And the more I practiced, the more self-awareness I cultivated.

“It’s natural to develop a coping mechanism that reinforces our biases and makes them worse,” says Goerling, who, like others in his profession, has seen public trust in the police plummet. Implicit bias, says Goerling, is “the dirty little secret” in police departments. “Mindfulness is the one skill I have come across in my 20 years of law enforcement that promises to improve the individual and radically change the performance of the police officer and radically change the relationship of the police officer to the community,” he says.

Goerling has set up the Pacific Institute in Oregon to train police officers, based on the eight-week Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR) pioneered by Jon Kabat-Zinn at Massachusetts General. “All of the technology in the world—cameras on police officers, etc.—won’t help until we work with the police officers themselves, until we begin to offer programs that make them resilient, empathic, and compassionate—and still battle ready,” says Goerling, who now speaks to police departments around the globe. “We need to understand our perceptions of the world and how we bring our biases into the judgments we make about other people.”

If Goerling had his way, every police department everywhere would have such a program. “It’s about transforming the culture from the inside out,” he says. “On both sides of the badge there is deep suffering.”

And there is mindfulness on both sides of that badge, and with that may come unseen possibilities, even when things seem dire.

Photograph by Mark Mahaney

On a spring day in late April, when the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray while in police custody caused angry residents in Baltimore to riot, the founders of the Holistic Life Foundation, Ali and Atman Smith and Andy Gonzalez, were not surprised. These three, who started working with young people in the inner city in 2001, are a picture of unity within diversity. Their personalities diverge widely, and they argue and cajole regularly, yet they speak with one voice and work off the same page of the playbook. “We know the trauma these folks have grown up with and the anger that can cause,” says Atman, “and that’s why we’ve been working here for so long, to get these young ones to find their own inner resilience through yoga and mindfulness,” he says, “so they can be part of making this city an environment you can thrive in.” Andy added that, “You know what? The people who have trained with us have been out there cleaning up after the mess and raising the spirits of the community. They are sad about the destruction, but they are answering the wake-up call.”

On the Saturday following the riots, the group sponsored “B-More Love: Group Meditation to Increase Peace and Unity in Baltimore City” in the heart of their neighborhood, which is right where the riots began. “We need to boost up the love vibes,” Ali says, “and get some people together who don’t look like each other to solve the problem. Get them to be mindful together. Too much separation in Baltimore right now.”

In the Heat of the Moment

Take a journey through bias with awareness and kindness with Vinny Ferraro

The path of mindfulness, awareness, kindness, and compassion will take us as deep as we’re willing to go. Not only can it help us to relieve our stress, but it can arouse in us the courage to pull back the curtain and honestly face our patterns and conditioning, tracing them back to unconscious stories that shape how we see the world, and the other people in it.

It can be helpful to notice our preconceptions and stories in the quiet of a meditation session, but it can also be powerful to notice our biases on the spot, in the heat of the moment, and switch things up. Here are some steps to consider.

1. When you notice habits overtaking you, bring out the compass

Based on some old information, you find yourself trapped in a habit pattern. You’re prejudging a person, people, or a situation, and it’s all attached to a story you’re holding onto: These people always…

When lost like this, you need to find out where you are, what’s really happening in your mind as it interprets what’s in front of you. Do you feel uncomfortable, awkward, nervous? Are you reacting more to the story about the situation than the present circumstances? Are you disengaging and distancing yourself from what’s right there?

2. Get the lay of the land

It’s good to familiarize yourself with the territory, the terrain of what you’re uncovering in your mind. Consciously explore yourself and your patterns particular to these conditions: Every time I see this, I think this…

When you can see the lens you’re looking through, you can see the stories that have been running you and the reason you’ve lost touch with the living, breathing people in front of you.

3. Venture into uncharted territory

Acknowledge the story or stories that are governing your responses. Question them. Being doggedly honest is the key here, no matter what comes up. Ask yourself:

What is informing this story? Why would I think that?

This happened and what I made that out to mean is…

The culture or the system I’ve grown up in may play a role in shaping my stories, but is there anything going on that I can own?

4. Surrender the safe territory of what you think you know

Having taken a fresh look at what’s going on, it’s time to consider the possibility that you are not seeing the whole picture. Now that you’re loosening your grip on your version of things, ask yourself whether you like what you’re contributing to the present moment, both internally (in your mind) and externally (in your actions).

If you allow yourself to stay stuck on your original habit pattern, and have the same old reaction, you won’t really notice the impact you’re having on others. You will feel what your story tells you to feel.

Better to feel the vulnerability of not being right—or at least not quite so certain. Not knowing is tenderhearted.

5. Find a bigger map

Our map of the world and our place in it is so often too small. Our stories have shrunk what is a very big and wild place and left out a lot of tribes and a lot of terrain.

Reflect on and update your GPS. Connect and realign with your actual beliefs and values, the ones you hold deep down. Educate yourself, break the old cycles, cut a new groove.

Following this kind of process in the middle of things may seem difficult, but it really doesn’t take long to examine and dislodge our story, and we can do it over and over again. It may slow things down a bit, but that’s not so bad.

And remember the old saloon wisdom: “If you sit down to gamble and you don’t see the sucker, it’s probably you.” Where our biases are concerned, if we don’t see what the big problem is, we may be a part of it.