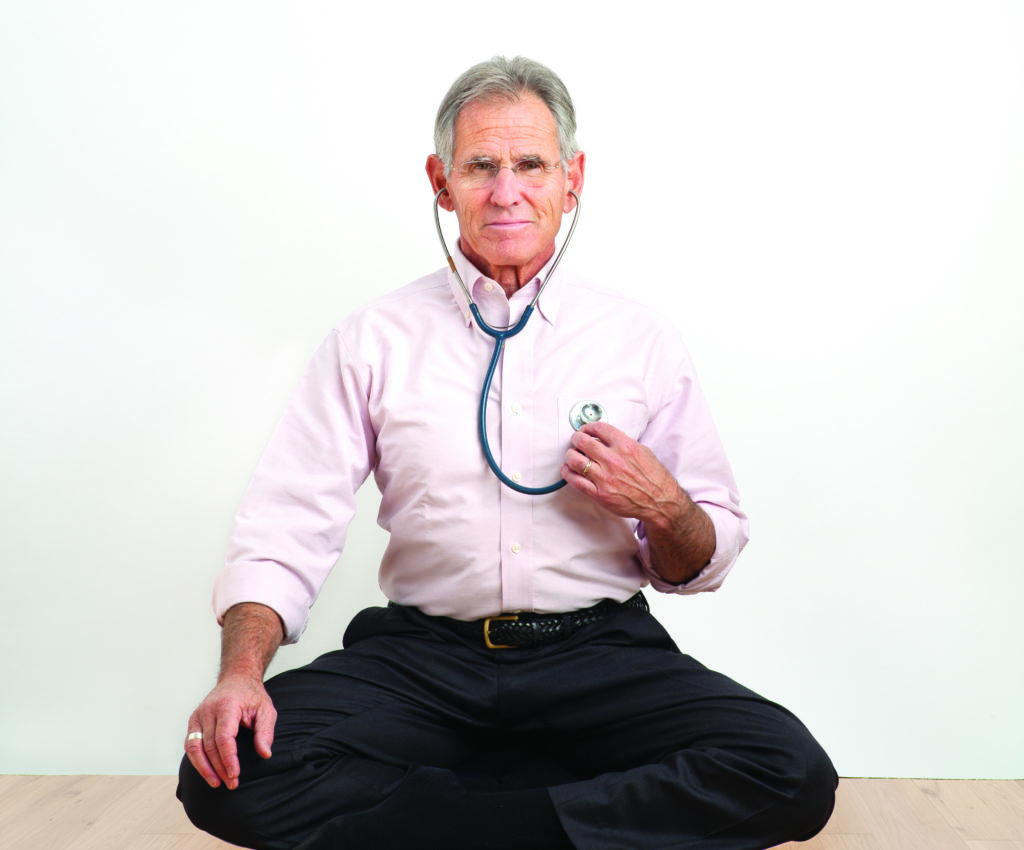

Who is Jon Kabat-Zinn?

In 1979, Dr. Jon Kabat-Zinn, a microbiologist working at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester (UMass Medical School), MA, started a modest eight-week program called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction—inviting patients to take some time for self-care down in the hospital’s basement. More than forty years later, MBSR is taught the world over and has become the gold standard for applying mindfulness to the stresses of everyday life and for researching whether mindfulness practice can improve mental and physical health.

Kabat-Zinn is also the founder of the Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society at UMass Medical School. He is author of Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness; Wherever You Go, There You Are; Coming to Our Senses; and Mindfulness for Beginners. He trains, teaches, and lectures throughout the world on applications of mindfulness and is Professor of Medicine Emeritus at UMass Medical School.

Kabat-Zinn has emphasized that mindfulness is not a mental trick. Rather it is a basic human inheritance that is essential to life. We need to be optimally aware of who we are, where we are, and how we are in order to survive individually and as communities, and even as a species, in Kabat-Zinn’s view.

Jon Kabat-Zinn MasterClass

Jon Kabat-Zinn speaks with Mindful’s founding editor Barry Boyce about his new MasterClass, and how it’s really about non-mastery.

Barry: Let’s start off with a very basic question: is mindfulness a state of mind, a fundamental capability, a practice, et cetera? In a time when the word gets used an awful lot—a lot more than back in 1979. What do you think’s most important to emphasize about mindfulness, what it is and why it’s important?

Jon: Well, it’s both a formal meditative practice that has a lot of different dimensions and aspects to it, it requires some kind of commitment of time and energy to actually stop and drop into the only moment that we ever have to be alive in. We’re usually blasting through to get to some better moment at some future time when we get stuff off our desk or, whatever it is, off our to do list. So one, is that mindfulness is a whole repertoire of formal meditative practices aimed at cultivating moment-to-moment nonjudgmental awareness. And nonjudgmental, by the way, does not mean that you won’t have any likes or dislikes or that you’ll be completely neutral about everything. Nonjudgmental really means that you’ll become aware of how judgmental you are and then not judge that and see if you [can let go], for a few moments at least, the restraining order that filters everything through our likes and dislikes or wants or aversion. So that’s already quite an exercise, quite an undertaking to cultivate that kind of attention and that kind of awareness and learn how to reside inside it.

Then another aspect of mindfulness is pure awareness, is not just formal meditation practice, but in some sense living life in every moment that we have it to live.

So that means bringing one’s formal meditation practice out into the world and letting life become both the meditation teacher and the practice, moment by moment, no matter what arises. Which makes it very challenging because so many things can arise in life that create real hurdles and problems and stress and emotional pain and physical pain and everything else. So, this is a major undertaking.

What it is not is a particular state that, if you were really good at meditating, you’d be there and then you could get back to it whenever you wanted. And that’s your home base that never deviates. If you try to approach it that way, you’ll always be striving to get to some special state that you’re imagining is what mindfulness is all about and actually missing how special the condition of this present moment is, no matter what. One example being—if you’re listening to this with your ears, the miracle of hearing—that’s non-trivial. And how we actually decode vibrations that come into the ears and set that tympanic membrane—the ear drum—going and then ultimately getting resolved in the auditory cortex. What we’re talking about is a miracle here and that’s just hearing. So, then there’s seeing, feeling, tasting, touching and all of the different domains in which human intelligence arises, including thoughts and emotions. And what we’re doing is we’re embracing it all in awareness so that we can actually navigate moments with as much clarity, equanimity and balance as possible, and not merely to be balanced for ourselves, but for the sake of being in deep connection with what’s actually happening. And since we’re social beings, that includes all of the different ways that we’re folded into our families, into our history, into our society, into every aspect, including the planetary aspect of how we are in relationship to nature, Mother Nature and the future that we’re bequeathing to our future generations.

Barry: I want to get to that aspect of things a bit later on in our discussion. Just to go back to some of the things you were saying—you’ve been talking about mindfulness as an undertaking, and not a state but, is there a natural capability there that we’re cultivating, that’s already available to everybody?

Jon: Well, you’re right on target because, of course, you’ve been practicing for decades yourself. And there’s no one right way to practice, by the way. So there are lots of different doors into this room of mindfulness and lots of different traditions that are grounded in mindfulness. The doorways may look different, but the room to a first approximation is the same. So, part of it is that you’re willing to actually drop into the present moment, as I said, and apprehend the actuality of it. To do that requires a certain kind of grounding in being—and we’re so into doing and getting someplace else that we’re not actually that in touch with being in the present moment unless things are exactly the way we want them to be. So, the approach is to really befriend yourself and see if you can actually take up residence in the domain of being, by resting in awareness which you don’t have to acquire, you’re born with the capacity for awareness. What we are acquiring with mindfulness as a formal practice is access into this core aspect of our humanity, which, you know, I sometimes say could be the final common pathway actually of what makes us humans as the species Homo sapiens sapiens. And this awareness doesn’t get that much air time in school, at least until recently. Now it’s changing. But actually recognize that aside from thinking, which is a fantastic form of intelligence, and then there’s emotional intelligence and social intelligence, the core intelligence may be awareness itself, which is very poorly understood scientifically. But the fact is that everybody already has it, so that means there’s nothing you have to acquire.

Befriend yourself and see if you can actually take up residence in the domain of being, by resting in awareness which you don’t have to acquire, you’re born with the capacity for awareness.

Jon Kabat-Zinn

What we’re doing in the formal meditation practice is in some sense sweeping things out of the way so that we have access, we’re clearing the brush, so to speak, that’s kind of occluding our capacity to really rest in awareness, to inhabit the field of awareness. And the best place to start is with the body, the body is the first foundation of mindfulness.

So, can we bring awareness to our body with a certain kind of openness and acceptance that doesn’t have us falling into liking and disliking what’s going on with the body, but learning how to in some sense take up residency in awareness of the body? And then that’s kind of like a platform for everything else in human experience, because there’s a lot more going on than merely the body.

Present-Moment Awareness and the Body

Barry: Let’s talk about the body a little bit. Is it possible to over identify with the body? We have a lot of body neuroses. So how do you counteract that in the practice?

Jon: Very simply, Barry, you ask questions about who’s claiming that it’s my body. And that turns out to be a very interesting inquiry because we say things like, “I’m breathing,” but we know that we’re so unreliable. Plus, the fact that we’re asleep for a lot of the time means that if it were up to us to be breathing, we would have died a long time ago. So although we say, conventionally speaking, “I’m breathing,” it is much more complicated than that. We don’t know who’s actually making that claim and it’s the same for, “I have a body” or “I like my body,” or “I detest my body” or “I liked my body 35 years ago, but I don’t like it now because…” and then all of that is actually just very, very simply called thinking. That all those things are not the truth. And now that we’re in this domain, in the world where the truth itself is whatever you think it is, because with what’s going on in the world, people live in their own truth bubbles. So, one of the really profound, liberating aspects of the practice of mindfulness is actually recognizing thoughts, and then realizing that they may be true to a degree, but then none of them are actually absolutely true and a lot of them are based on preferences and on selfing, a kind of “I like this, I don’t like that. I want this. I don’t want that.” And when you bring awareness to it, then all of a sudden you see that those are like weather patterns in the sky of the mind. They’re not the truth about anything. And then in that very moment, you’re freed up from your own biases. You’re freed up from your own thought patterns that identify you in one way and identify other people in another way and very often disregard our common humanity and the fact that we are 99.7% genetically speaking in terms of our DNA, the same all over the planet. And of course, this creates enormous problems of one kind or another. So, just to finish off this piece, it’s very important that people understand and this is one of the main things that I emphasize in the MasterClass program is that it’s not about trying to get anywhere else. It’s allowing ourselves to be where we actually are. And so from that point of view, and I emphasize this a lot—crazy as it may sound, there’s no place to go, there’s no better moment than now. There’s nothing to do. There’s no special something that you need to attain and when you gift yourself that kind of moment, all of a sudden, it doesn’t take very long, you actually realize that you’re at home and being at home, you have a vast repertoire of thoughts, emotions, sensations in the body, feelings about this, that and everything. But none of that’s you. So, then you can actually navigate that domain in a way that has some degree of wisdom in it, some degree of kindness and compassion in it, because you don’t have to be in an adversarial relationship with the world, even though there’s a huge amount of suffering in the world, so therefore we can actually contribute to relieving that suffering, not just our own, but globally.

One of the really profound, liberating aspects of the practice of mindfulness is actually recognizing thoughts, and then realizing that they may be true to a degree, but then none of them are actually absolutely true.

Jon Kabat-Zinn

Barry: So this paradox, really, of not trying to get anywhere, I mean, we show up in the first place to practice meditation because we have some sense that we’d like to do something about something or other. At the same time, as you’re pointing out, if you’re trying to get some place, the preoccupation becomes about getting to be some place else…

Jon: Which is a big mistake, because if you get off on the wrong foot, 30 years down the road, even if you’re practicing meditation, you’ll still be on the wrong foot in a certain way and deluded about some core aspects of what’s being invited to be embodied in the present moment.

A Non-Master MasterClass

Barry: So this is called MasterClass. How does mastery fit in in the context of meditation?

Jon: I don’t want to give too much away, but MasterClass has its own kind of culture and everybody who offers a MasterClass, if you’ve watched any of these, says, “hi, my name is so-and-so and this is my MasterClass.” And I found that I was not able to do that. I did not want to do that because my own particular orientation towards this is that it’s not about mastery, it’s about being good enough. For what? For whatever it takes for you to live the life that’s yours, to live with a degree of happiness, kindness, a sense of belonging, a sense of meaning and purpose. So I say, when I’m introducing the MasterClass, I say, you know, hi, my name is Jon Kabat-Zinn and this is my non-master class. So, I’m inviting anybody who wants to engage with me in this series of 20 sessions to actually drop into exactly what we’re talking about, not trying to get to some better place where you’ll be a master of stress or of pain or of emotional imbalance or anything like that, but to simply trust that you’re more or less OK as you are and the more you pour energy into what’s right with you, as opposed to simply focusing on what’s wrong with you and trying hopelessly to improve yourself, the more you can actually recognize and then embody your beauty and your wholeness right in this moment, which is what meditation practice has been about for thousands of years.

Barry: While you are not claiming the title of master, which I understand, but you do have a legacy or two, of course, one of them being Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). While you’ve been very careful about creating a protocol and guidelines and guardrails there, you’ve also avoided being strictly canonical that there’s absolutely one way to teach this, there’s absolutely one way to talk about this.

Jon: Thank you for recognizing that.

Barry: Why is that important to you, Jon?

Jon: Holy cow. I mean, that’s phenomenally important to me because mindfulness is really based on a certain kind of liberated wisdom that has never been more important in the world than it is now. And the more we get caught up in dualisms of one kind or another, as I was suggesting—and one of them would be, I’m not good enough, I’m going to strive to be the greatest meditator or the most mindful person I can be. So if you’re teaching MBSR and you’re conveying that kind of thing to people with chronic pain, chronic stress, chronic diseases like cancer and heart disease you’re not teaching mindfulness, you’re teaching some kind of acquisitive capitalistic attempt to get on top of some problem solving in one way or another. Whereas the liberative dimension of meditation practice is to start where you are and be fully present and apprehend the interior and the outer landscape of what’s available. In any moment that you drop underneath your thinking, for instance, without trying to suppress it or make it go away or pursue it—which we’re totally conditioned to do—then in a very real way, you’re free in that moment. You’re still breathing, still alive. You may have this going on or that going on in your life, but now you have a way to be in a wiser relationship to it. And the part of you that’s resting in awareness or that’s inhabiting the space of awareness, there’s nothing wrong with you and there never has been.

Mindfulness is really based on a certain kind of liberated wisdom that has never been more important in the world than it is now.

Jon Kabat-Zinn

And so that’s a way to take hold of your life. Now, that’s the core of MBSR. How you get people who have not grown up in a meditative tradition so that they come to MBSR through the love of these ancient meditative practices, but with a way of reconfiguring them so that they make common sense to virtually anybody and don’t have the sense that you’re trying to convert somebody to some kind of religious perspective or philosophy or anything like that, that’s a very tall order. And I’ve always trusted that in a certain way beyond a certain point, no matter how much we train MBSR teachers, this is not a trainable skill.

Yes, you need a whole repertoire of trainable capacities to walk into a classroom with 30 or 40 people who are suffering from unimaginable things that you would never want to have yourself. How are you going to hold the space for their wholeness, when you yourself know that you’re not always so whole? So, my faith is, and it’s been confirmed hundreds of thousands of times over the past 40 plus years, as you’re alluding to, of MBSR, that when we give people the basic core curriculum of MBSR and they understand it from the inside through their own meditation practice, and they stay with the curriculum, which is kind of like the space in which those eight weeks unfold and they bring their own meditation practice to it—they will know how to teach it. They will know how to be in wise relationship with what arises spontaneously in the classroom that you can’t prepare for. And if you do sort of prepare in a certain way that is scripted, then when someone comes up with something profoundly painful and you respond to it with a scripted response that’s not in the present moment, every single person in the room will know that you’re basically simulating, you’re faking something. You’re not being authentic yourself, but you’re inviting everybody else to be authentic. So, I think it’s actually impossible to be an MBSR teacher…and that’s why I love it so much. Because it basically asks people to devote themselves to the meditation practice in some way that what they’re teaching is their own understanding of being and allowing everybody else to find their own way in, and good enough is good enough. We’re not talking about mastery. We’re not talking about achieving some mindful state or some state of utter global compassion where we’re saints walking around in human bodies, but that we’re humans actually recognizing how beautiful the opportunity is to live life from moment to moment.

Barry: Yeah, that’s quite beautiful. I think if it were more oriented towards being a self-improvement program then the teacher or trainer would be understood as trying to manufacture an experience or an endpoint for somebody rather than embodying something together, exploring together with people, using the curriculum and the set up as a container for that activity, as opposed to, “OK, here’s where you need to be, here’s the outcome.” You know, there’s a certain amount of uncertainty.

Jon: You’ve got that exactly right. And if you’re not comfortable as a teacher with that uncertainty, basically you’re painting by the numbers and people will recognize that immediately, that you’re basically following some script, but you’re not living it. So therefore it’s not alive. And the interesting thing is that people love to teach this, and I don’t really observe too many people teaching MBSR, but I can tell how good the teaching is by what their students say and how their students are.

When people say this has completely transformed my life, they’re not kidding around because they’ve in some sense liberated themselves from old scripts or narrative about who they were or what they were capable of, where their life was supposed to go. And they are now working with the real life material of authenticity embodied…authenticity and a profound sense of interconnectedness. So this is a way to actually stop for a moment and remember and reconnect with what life is really about and not get caught in all the little seizures that we might have when things are not going our way or when we’re feeling stressed.

And this is applicable, by the way, not just to middle class or privileged people who have everything and now they need to put mindfulness on top of it. I mean, this is basically a core human faculty that virtually anybody can make use of, no matter what their circumstances, no matter what their situation, because it is an invitation to actually bring the entirety of your being into the present moment for the benefit of optimizing well-being and minimizing harm both to yourself and to others.

Barry: You know, when somebody says, that changed my life, it’s that script that folks may have held onto for a long time, that they’re beginning to feel liberated from. But ironically, it’s not necessarily that meditation gives them a shiny new script. It’s like you have the confidence that you might be able to get by without a script.

Jon: Yeah, the script of No Script, so to speak. The awareness can hold all sorts of narrative stories that we build up about ourselves. But this loops back to something you brought up earlier, and that is the question of not just who’s breathing, whose body, but who’s writing these scripts? And who says they’re true in any kind of profound way? And then when you recognize that your awareness isn’t limited or imprisoned by the scripts, the scripts, you could say, liberate themselves. They no longer have that kind of power to keep us locked up in a prison that we create for ourselves—this narrative that I’m too old or I’m too this or I’m not enough—and ask instead for us to question who’s talking. What are these personal pronouns about, this I, me, and mine.

And again, let me just say that because people might be wondering, well, why the hell would I do a MasterClass? Since it feels like a certain kind of elitist, privileged kind of thing. And the reason I did it is because, first of all, I was really touched by the person who invented this and his commitment to actually making this available to people who would never have the wherewithal or the interest in subscribing to the sort of glitterati of the MasterClass. And so we’re making every attempt to actually reach a whole range of different kinds of people. We’re trying to figure out how to do that. And it’s really a collective effort. It’s not just me, but the whole orientation is around that. But that is what I tried to do in these 20 lessons in MasterClass is actually just visit every aspect of what you and I are talking about now in terms of the depth of the meditation practice, but how easy and understandable it is to actually enter into these waters and then just see what happens and let the practice do you rather than you doing the practice. Because that feels like, oh, just one more thing I have to add to my already too stressful, too busy, too preoccupied day. It’s not about mastery, but more about inhabiting the full dimensionality of your being when you let go of not just the narratives, but the generator of the narrative. So, who’s generating those narratives? I, me, and mine… the personal pronouns.

Healing the World

Barry: You know, one of the later segments in your MasterClass series I notice is called Healing the World, and your book Coming to Our Senses has been a favorite of mine. It laid out a kind of a social mission emerging from mindfulness, is that what you are treating in the Healing the World segment?

Jon: Very much. You know, again, none of these are comprehensive, but they’re all pointers to something, mindfulness is not simply about sitting on a cushion and experiencing oneness with the universe. But it’s actually recognizing the enormity of that greed, hatred, delusion and suffering the ocean of which we are swimming in. And the profound repercussions of it that we’re seeing played out in the world of politics around the world, but in particular in the United States at this moment, and how to heal from some of those wounds—but then how to not repeat them either, which means it’s not just a matter of these people being in power, those people not being in power or being more or less in favor of these social programs or those social programs.

Mindfulness is not simply about sitting on a cushion and experiencing oneness with the universe. But it’s actually recognizing the enormity of that greed, hatred, delusion and suffering the ocean of which we are swimming in.

Jon Kabat-Zinn

But a question of what is the nature of the human mind and the human species. How can we learn to live together? The kinds of weapons we have and the kinds of effects we’re having on global warming, we just can’t keep this up. Humanity itself is the autoimmune disease of planet Earth in a certain way. And if we don’t live our way into the name Linnaeus gave us as a species, Homo sapiens sapiens, which means basically the species that is aware and is aware that it’s aware from the Latin Sapere, which means to taste or to know—we may not make it as a species or we may create a world in very short order where the suffering on our children, never mind our grandchildren or future generations, will be so immense and we will not be able to blame it on anybody else, it would be self-generated. So, there’s never been a more important moment in the history of humanity as far as I’m concerned, for us to actually wake up to our true nature. And if there were anything more powerful in that regard or adequate for that enormity of undertaking than mindfulness, I would not be teaching mindfulness. I meant MBSR from the beginning to be a political act. It wasn’t just another therapy that we would introduce into medicine or psychology. That was a skillful means for actually demonstrating proof of its value or concept and developing a science of mindfulness to the point where it would move out into the world in ways where we might actually begin to, on a population-wide level, on a global level, challenge ourselves to not fall into a kind of lethal, us-ing and them-ing, no matter how much we disagreed with other people. But to actually inquire about our commonality in a way that would minimize harm on every level that harm could unfold and maximize well-being and happiness and safety, because that’s what health really is. Whether you’re talking about mental health, physical health or the health of a nation or now the very real health of a planet. So that’s what it was about from the very beginning. And Coming to Our Senses was really my attempt back in the early 2000s to frame this so that it’s understood that this is not merely a stress reduction approach for your own simple well-being, but that it had profound repercussions simply because of the interconnectedness of things and, if you will, the law of impermanence.

Barry: Well, it’s kind of a public health approach writ large.

Jon: Totally.

Barry: And, you know, in that regard, many people who would come to a practice of mindfulness feel profoundly unhealed or unhealthy themselves and feel like perhaps how could I even think about healing the world when I’m such a mess myself? Is it necessary to heal oneself first? Is it sequential like that? OK, I have to get healed first, and then I can begin to think about healing others and the world or, how do you understand the continuity from one’s own healing to a larger kind of healing?

Jon: I think there are probably a lot of different ways and different people will all approach it differently. I do think that to the degree that one is in touch with one’s own suffering, one can use that to recognize suffering in others, and even if you don’t actually do anything. If you are beginning to feel the suffering of others, that’s kind of not just empathy, but it’s compassion, if something is moving in you that’s actually moving you. And so from that point of view, the more we cultivate this combination of formal meditation practice ourselves to fine tune the instrument and then life itself being the meditation practice, and in some sense a radical act of sanity and love. Then we can actually begin to see that how we be in the world already makes changes, small, incremental changes, but profound, especially when they’re embodied.

And then if large numbers of people take this on, which they are more and more, globally, all around the world, then all of a sudden we will be able to make a difference. And this is happening already. There are initiatives in the UK and in France and in Holland and in the Scandinavian countries where mindfulness is now moving into government, it’s into moving into politics. The vice premier of Belgium, who is also a physician, talking about her mindfulness practice and how it helps her relate to the political challenges that she’s dealing with in Brussels, related to not just Belgium, but to the entire EU, the health of Europe, so to speak. And while that might sound like the far side of the lunatic fringe to bring meditation into the mainstream. Well, you know, I think that the 40 plus years of MBSR, and all the other mindfulness based programs that are developed along similar lines to deal with other aspects of life, have reached the point where there is a certain critical mass or critical momentum, where this no longer seems like the lunatic fringe. It feels like in some sense, a lifeline that’s being thrown to humanity.

And it’s like, “hey… do you want to wake up now or do you want to fall into some kind of horror hell realm that’s going to be very, very hard to back away from, beyond a certain point?” So mindfulness of the world or healing the body politic, as I put it, is as absolutely important as healing the body. And just like our body is made of trillions and trillions of cells, the body politic is made up of trillions and trillions of cells. And the more that we recognize that each one of us is a cell of the body politic, the more healthy we are and the more we take care of the other cells in our neighborhood and maybe in all the various kinds of ways in which the different tissues are connected. We don’t go to war with each other and create an autoimmune disease of planet Earth just when we have the potential for profound healing.

Barry: Well, thank you, Jon. I mean, we’ve gone all the way from mindfulness of the body to mindfulness of the body in a very, very big way. It’s always a pleasure to spend time with you and hang out. I know that our readers will enjoy that and that this MasterClass, non-master class will reach a lot of folks and do a lot of good.

Jon: Well, thank you, Barry. It’s always my pleasure to talk with you and to be in touch with the broad audience of people who care about mindfulness and are part of the Mindful family. And so I just want to say in closing to everybody who’s been reading that every single one of us is important in this. It’s not like you’re listening to some master who’s putting out the way things are. You are in some sense, to whatever degree you care to take on this karmic assignment, the master of not only your own life, but your own relationships with others and with reality. And this is a really profound love affair with what’s deepest and best in all of us as humans. And there’s no one right way to do it. And there are no heroes or heroines on white horses that are going to rescue humanity. This is up to every cell of the body politic to, in some sense, connect with what’s most beautiful in yourself. And if that’s what meditation practice is, which is from my point of view, exactly what it is, then getting your ass on the cushion, so to speak, for the formal tuning of the instrument, and the reclaiming of your possibilities becomes a radical act of sanity and love rather than just one more thing I have to fit into my already too stressful and busy day. So, thanks.

Barry: Thank you, Jon. And till next time, be well.

Jon: You too.

What is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MSBR)?

MBSR was built on the conviction that the insights, wisdom, and compassion of the meditative traditions were equal in import and magnitude to the great discoveries about human life made in the West. If there’s an instruction manual for being human, then Western science and medicine have supplied one part of it, and the contemplative traditions have supplied another, the part that has to do with discovering and cultivating our deep interior resources.

Kabat-Zinn’s hope was that by starting a stress-reduction clinic based on relatively intensive training in mindfulness meditation and yoga—and their applications in everyday living—we could document how these practices might have a profound effect on the health and well-being of individuals. The larger purpose was to effect a kind of public-health intervention that would ultimately move the bell curve of the entire society.

The 8-Week MBSR Program

The eight weeks of the MBSR curriculum offer a reliable protocol that is used in many studies of the effects of mindfulness meditation practice. People who have taught it a lot have seen that it has an integrity of its own. If they try to switch things around—a little more of this, a little less of that, take this out, put this in—they find it isn’t as effective, Kabat-Zinn says.

Yet it’s only a framework. It’s only as effective as what the teacher brings to it and how they “holds the space,” as we say. It simply will not work if it is scripted or formulaic. If the teacher doesn’t feel competent in one of the elements, say yoga, it doesn’t work if they bring in an outside expert. They have to get the training and embody it themselves.

In an interview with Mindful, Kabat-Zinn said, “As a teacher, you are trying to convey something that can’t be conveyed in words. Mindfulness is also heartfulness—you need poetry as much as prose. What truly makes mindfulness training work is love. If the teacher holding the class is profoundly in love with what they are doing and with the people in the class in a fundamental way, it will work. If they are not, it will peter out.”

The Foundational Science of Mindfulness-Based Interventions

Mindfulness meditation studies were coming out of Kabat-Zinn’s Stress Reduction Clinic as early as 1982. Since that time, more than 25,000 people have completed his groundbreaking multi-week program, which came to be known as MBSR, learning to build their capacity to respond to stress, pain, and even chronic illness.

Kabat-Zinn applied the basic principles of mindfulness meditation to patients in a medical setting and his work developing the MBSR program proved effective in helping alleviate the suffering of previously debilitating medical conditions such as chronic pain. It also served as fertile ground for a systematic set of research investigations in collaboration with one of the founders of the field of affective neuroscience, Richard Davidson of the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

The Future of Mindfulness

In 2015, Kabat-Zinn spoke to Mindful about the future of mindfulness for a four-part video series.

You Are Not Your Thoughts

Watch the Full Video:

Mindfulness is the basic human ability to be fully present, aware of where we are and what we’re doing, and not overly reactive or overwhelmed by what’s going on around us. “And then I sometimes add, in the service of self-understanding and wisdom,” says Kabat-Zinn.

“We all take ourselves too seriously because we believe that there’s someone to take seriously. That me. We become the star of our own movie. The story of me, starring, of course, me! And everyone else becomes a bit player in our movie. And then we forget that it’s a fabrication. It’s a construction. And that it’s not a movie and that there’s no you that you can actually find if you were to peel back.”

Are you your name? Are you your age? Are you your thoughts? Are you your opinions? Are you your genetic inheritance?

Even your genes, if you meditate, or eat differently, they’re going to be expressed by the hundreds differently. So, you’re not even your genetic inheritance. So, who are you?

And here’s where the rubber really meets the road: The question is much more important than the dimestore answers that we come up with.

So, then we can notice this phenomenon called “selfing.” How much of our time we are running the narrative of “I” “Me” and “Mine” which is now being identified with certain regions of the brain that do that narrative default mode kind of thing. And then mindfulness MBSR has been shown to light up other areas, more lateral areas, where there’s no more story of “me.”

Why Nonjudgment is Part of Mindfulness Practice

Watch the Full Video:

Kabat-Zinn adds to his definition of mindfulness by describing it as “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, nonjudgmentally.” Nonjudgmentally is the key word here. He says it adds an element of discernment of thoughts: an ability to see the whole picture, conceptually and non-conceptually. “It’s about knowing what’s on your mind,” he says. And knowing that you can have a wise relationship with unpleasant thoughts that may be rooted in greed, or delusion.

It’s a Mindfulness Revolution—But it’s Only the Beginning

Watch the Full Video:

The Mindfulness Revolution isn’t going to happen all at once, Kabat-Zinn says. But he argues that bringing mindfulness into the mainstream of society has the potential to help humanity find a way to “not let our self-destructive and other destructive impulses wind up doing unimaginable levels of harm.”

Ultimately, mindfulness can help break down the “us versus them” mentality that dominates the global political scene—and we cannot become mindful nations without this key shift. It comes back to the fact that mindfulness isn’t mindfulness without “heartfulness,” Kabat-Zinn says.

The Beginning of Mindful Nations

Watch the Full Video:

Kabat-Zinn speaks about his trip to UK Parliament, and how the concept of a mindful nation is being adapted in the UK, as well as in the US by Congressman Tim Ryan.

Mindfulness Meditations Guided by Jon Kabat-Zinn

A Guided Meditation on Observing Thoughts, Nonjudgmentally

A Guided Meditation on Observing Thoughts—Jon Kabat-Zinn

A Guided Meditation for Resting In Awareness

A Meditation for Resting in Awareness—Jon Kabat-Zinn

This Loving-Kindness Meditation is a Radical Act of Love

A Loving-Kindness Meditation For Deep Healing—Jon Kabat-Zinn

A Full Body Scan Meditation

With steady, loving attention, we can calm the mind, notice sensations in the body, and bring awareness to the present moment.

Jon Kabat-Zinn in Mindful Magazine

In the February 2014 issue of Mindful magazine, we talked to the health and well-being pioneer about why mindfulness has attracted so much attention and why it will continue to do so.

Mindful: Did you ever think the work that started in a modest clinic in a spare room of a hospital in Central Massachusetts would become so influential?

Jon Kabat-Zinn: In a word, yes. I never thought of this work as a small thing. I don’t think of myself as a big deal, but I always thought of this work as a very big deal. It wasn’t just about thinking that meditation had a modest contribution to make to Western medicine. MBSR was built on the conviction that the insights, wisdom, and compassion of the meditative traditions were equal in import and magnitude to the great discoveries about human life we’ve made in the West. If there’s an instruction manual for being human, then Western science and medicine have supplied one part of it, and the contemplative traditions have supplied another, the part that has to do with discovering and cultivating our deep interior resources.

My hope was that by starting a stress-reduction clinic based on relatively intensive training in mindfulness meditation and yoga—and their applications in everyday living—we could document how these practices might have a profound effect on the health and well-being of individuals. The larger purpose was to effect a kind of public-health intervention that would ultimately move the bell curve of the entire society.

Mindful: And it grew to the point where we now talk about mindfulness-based interventions in all sorts of areas—depression, childbirth, education, addiction, to name just a few.

JKZ: We didn’t have a specific blueprint, but I am very gratified that so many developments have been happening on so many different fronts. It’s really a matter of planting seeds. You never really know what will sprout from these seeds and how they will spread. That’s the beauty of it. It’s based on not-knowing—approaching the world inquisitively, with a fresh mind.

If we had come in with a plan, with an ideology, with all the answers, I think it would have remained small. Instead, those of us involved in this work have paid close attention to just a few essential elements. One is that mindfulness is not a special state you achieve through a trick or a technique. It is a way of being. I have a lot of faith that if people just learn how to be in the present through simple mindfulness meditation, then the practice does the work of transformation and healing. We do not need to do it for them. People are so creative and intrinsically intelligent that given a chance, they perceive the truth within their own experience. “When I get attached to something, I suffer,” they realize, “and when I don’t get attached, I don’t.”

Mindful: The benefits of mindfulness go far beyond stress reduction. Why did you call your program that, and are you still satisfied with your choice?

JKZ: I wanted it to speak to universal experience. Everybody can relate to stress. It’s a common English word and a common experience. The science on stress is proving that it was a good choice. We find out more every day about the negative effects of stress on the body, on the immune system, on aging, and so on. Likewise, there is a correspondingly strong interest in how we can develop resiliency in the face of stress, which is a benefit of mindfulness practice.

Mindful: You often say that mindfulness is not about attaining benefits or fixing problems—that it’s about discovering there is more right with us than wrong with us. Yet a “stress-reduction” program can seem very benefit-oriented.

JKZ: That is an unavoidable paradox. There are tremendous benefits that arise from mindfulness practice, but it works precisely because we don’t try to attain benefit. Instead, we befriend ourselves as we are. We learn how to drop in on ourselves, visit, and hang out in awareness.

It’s essential when you’re teaching mindfulness to remember this and embody it in your own way of being. People come to a mindfulness course because they’re in pain or angry or depressed or afraid. The one thing they want is to get somewhere else, so the teacher needs to continually convey that mindfulness is not about getting anywhere. The teacher’s own practice and way of holding him- or herself communicates that, and because people are intelligent and inherently mindful, they resonate with it. At that point, it becomes ordinary common sense. People often say, “I always figured meditation was something weird and mystical. If only I had known what it really is I would have started years ago.”

Mindful: Your interest is not just working with medically defied pain, but with all of life—“the full catastrophe,” in that colorful phrase you borrowed from Zorba the Greek.

JKZ: People say, “I came to this program to deal with my pain. I didn’t realize it was about my whole life!” There was a professor I knew from my MIT days who needed a bone-marrow transplant, and he showed up at the clinic in Worcester. He said, “I want to learn how to be in relationship with my mind, so that when I’m in isolation in the transplant unit, I can survive it.” After a few MBSR classes, he said, “I feel more comfortable with these people I’ve just met than I do with the colleagues in my department.” When he asked himself why, he concluded, “This is the community of the afflicted, and we acknowledge the affliction. The faculty is also the community of the afflicted, but we don’t acknowledge our affliction at all.” Later, he was riding the subway and realized we are all “the community of the afflicted.” It made him feel extraordinarily free.

Mindful: If the real benefits take place in the heart and in our very way of being, why does the scientific work matter so much?

JKZ: David Black of the Mindfulness Research Guide has been gathering information on the number of scientific and medical papers per year on mindfulness, and the resulting graph is pretty telling. Something that was not on the research map at all a few decades ago is a prime area of interest now. These studies provide the evidence of effectiveness you need to be respected and adopted in key institutions in health care, education, social policy, and so on.

But ultimately we do science to understand the nature of the universe—and the nature of the one who wants to understand the nature of the universe. Research that helps us understand the capabilities of the brain and how to improve them is vitally important to how we can live well, as individuals and as a society.

The brain science has become very rigorous. A lot of credit obviously goes to Richie Davidson, in his lab at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds. Their work is unique in that it focuses on both basic science and translational research, which takes place in real-life settings such as Madison’s public schools. Research on how the brain can be trained ventures into areas we wouldn’t have dreamed of years ago. For example, one of the center’s really interesting projects, funded by the Gates Foundation, is to study the effects of computer games that train children in attention and pro-social behaviors, such as recognizing others’ emotions.

Many young scientists are now taking up this field, many with the support of the Mind & Life Institute’s Varela Grants and summer research institute, where contemplative practice is integrated into a scientific meeting. Young neuroscientists and behavioral scientists are building their careers in what’s now called contemplative neuroscience. Ten years ago that may well have been a career-ending choice.

One of the Varela researchers whose work I admire is Paul Condon of Northeastern University. His group designed a study to determine what different results might arise from training in mindfulness meditation and training in meditation that emphasizes compassion. In the study, participants received eight weeks of either mindfulness or compassion training or no training at all. Afterward, the researchers set up a scenario in which a study participant was directed to sit in a waiting room with only three chairs, two of which were occupied. After a minute, a fourth person entered on crutches wincing and sighing, and the two people originally in the room pretended not to notice.

The study measured how many participants would, during a two-minute period, overcome the bystander effect—if others are ignoring something, so should I—and offer their seat to the person on crutches. The people trained in mindfulness and the people trained in compassion were both fie times more likely to give up their seat as the people in the control group. There was no difference between training in mindfulness and training in compassion.

This raises some very interesting questions, and to my mind it underscores the fact that mindfulness is compassion and vice versa. Certainly, in MBSR, where people bring every kind of pain imaginable, compassion is naturally part of the atmosphere.

Mindful: When mindfulness reaches into our institutions of higher learning, it can have broad societal effects. Where else do you see mindfulness leading to bigger changes?

JKZ: Many well-known businesses and business leaders have been bringing mindfulness into their work and leadership, and I’ve had the opportunity to meet many of them, including at the Wisdom 2.0 conference every year. Some politicians, economists, and policymakers have started practicing mindfulness and bringing it into their work. It’s not many now, but the ones who are doing it are very passionate about it. Congressman Tim Ryan, whom I met five years ago when he did a mindfulness retreat with me, has become a strong advocate for mindfulness in health care, schools, the military, and particularly for veterans. He believes that programs that develop our innate human capacity to be mindful can make a profound difference for a relatively modest investment.

When I was in England recently, I spent a whole day in Parliament and visited with Prime Minister Cameron’s advisors at 10 Downing Street. Chris Ruane, a Member of Parliament from a very poor district in North Wales, has been instrumental in bringing mindfulness into public schools there, and he’s encouraging his colleagues to consider other ways to bring mindfulness into public policy.

I also gave the keynote at a daylong conference in London called Mindfulness in Schools. What I saw there brought me to tears. Here were seven-year-olds addressing 900 people, and they were completely self-possessed talking about their mindfulness practice and what it was doing for them. You could tell it was unrehearsed. They just spontaneously said what mindfulness meant to them.

Mindful: With all of this interest from so many different quarters, are there enough qualified people to serve the growing need for mindfulness teachers?

JKZ: The price of success is that more and more people want something. But of course, mindfulness is not a something. As I said in the beginning, it’s a way of being, and you usually discover it through someone who embodies it to some degree.

Interest in mindfulness generally, and in MBSR and other mindfulness-based programs, is spreading around the world at a lightning pace. So in addition to sowing seeds we need orchards, where we are growing things in a more structured and planned way. That has not been my emphasis, but fortunately there are people paying a lot of attention to that. At the Center for Mindfulness and in professional training programs all over the world, under Saki Santorelli’s excellent direction, people are learning how to teach mindfulness in a way that allows open discovery. The program certifies that they have been well trained, but of course we can’t certify that anyone is a good teacher. Each student will always have to judge that for him- or herself.

In the future, there will need to be many different kinds of mindfulness teachers and guides for many different contexts. What’s needed for educators will differ from what’s needed for health professionals and inner city youth. Let many flowers bloom.

The spread of mindfulness into more areas of our life is a multigenerational undertaking. One of the greatest challenges is how we will work with the digital revolution and the alternate reality it has created. Many of us are spending more time online than offline. We need to navigate this mindfully or it will eat us up. The technology itself is a source of endless possibilities but also endless distraction. We’re now very good at writing code—but how good are we at knowing ourselves, loving ourselves, and making a good world together with our fellow human beings?

Why You Should Listen to Your Body

Kabat-Zinn explores the relationship between mindfulness and body awareness, and the benefits of giving the body our full attention. In these excerpts from the April 2019 issue of Mindful magazine, he offers insight on how mindfulness practice enhances our very understanding of how we inhabit our own body as we make our way through life.

Body of Knowledge

We know that it is possible to lose the felt sense of the body or parts of it through traumatic injury. In spinal cord injuries, the nerves communicating between the body and the brain can be severely injured or severed completely. In such situations, as a rule, the person is paralyzed as well as being unable to feel his or her body in those areas controlled by the spinal nerves below the break. Both the sensory and the motor pathways between brain and body and body and brain are affected. The actor Christopher Reeve, who died in 2004, sustained such an injury to his neck when he was thrown from a horse.

A number of years ago, the neurologist Oliver Sacks, who died in 2015, described meeting a young woman who had lost only the sensory dimension of bodily experience due to an unusual and very rare polyneuritis (inflammation) of the sensory roots of her spinal and cranial nerves. This inflammation, unfortunately, extended throughout the woman’s nervous system. It was caused, in all likelihood and quite horrifically, by treatment with an antibiotic administered prophylactically in the hospital in advance of routine surgery for gallstones.

All this woman, whom Sacks called Christina, was left being able to feel was light touch. She could sense the breeze on her skin riding in an open convertible and she could sense temperature and pain, but even these she could only experience to an attenuated degree. She had lost all sense of having a body, of being in her body, of what is technically called proprioception, which Sacks calls “that vital sixth sense without which a body must remain unreal, unpossessed.” Christina had no muscle or tendon or joint sense whatsoever, and no words to describe her condition. Poignantly, in the same way that we see with people who lack sight or hearing, she could only use analogies derived from her other senses to describe her experiences. “I feel my body is blind and deaf to itself… It has no sense of itself.” In Sacks’s words, “she goes out when she can, she loves open cars, where she can feel the wind on her body and face (superficial sensation, light touch, is only slightly impaired).” “It’s wonderful,” she says. “I feel the wind on my arms and face, and then I know, faintly, I have arms and a face. It’s not the real thing, but it’s something—it lifts this horrible dead veil for a while.”

Lost Identity

Along with the loss of her sense of proprioception came the loss of what Sacks calls the fundamental mooring of identity—that embodied sense of being, of having a corporeal identity. “For Christina there is this general feeling—this ‘deficiency in the egoistic sentiment of individuality’—which has become less with accommodation, with the passage of time.”

Amazingly, she found her senses of sight and hearing assisting her with reclaiming some degree of external control over the positioning of her body and its ability to vocalize, but all her movements have to be carried out with extreme deliberateness and conscious attention. All the same, “there is this specific, organically based, feeling of disembodiedness, which remains as severe, and uncanny, as the day she first felt it.” Unlike those who are paralyzed by transections high up in the spinal cord and who also lose proprioception, “Christina, though ‘bodiless,’ is up and about.”

Make no mistake about it. Just as the loss of knowing who you are in sufferers of Alzheimer’s disease is in no way some kind of shortcut to selflessness, the loss of this proprioceptive mooring is not liberating in any sense of the word. It is not enlightenment, nor a dissolving of ego, nor the letting go of an overwrought attachment to the body. It is a pathological, utterly destructive process that robs the individual of what Sacks calls “the start and basis of all knowledge and certainty,” quoting the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. We have no words to describe the feelings we might be left with in the face of such a loss because the loss of the felt sense of the body, especially when the body can still move, is inconceivable to us.

From Oblivion to Body Awareness

“Those aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity. (One is unable to notice something because it is always before one’s eyes.) The real foundations of his enquiry do not strike a man at all.”

These are Wittgenstein’s words, with which Sacks opens his story about that “sixth sense” we so don’t know we have, so much is it in evidence, namely the felt sense of the body in space. It is so allied with our physicality, our physical “presence,” our sense of the body as proper to us and therefore as our own, that we fail to notice it or appreciate its centrality in our construction of the world and who we (think we) are. When we practice the body scan, our awareness includes that very sense of proprioception that Sacks is describing and that Christina tragically lost, the felt sense of having a body and, within the universe of the body as one seamless whole, the felt sense of all its various regions, which we can isolate in our minds to a degree, zero in on, and “inhabit.” When we practice the body scan, we are reclaiming the vibrancy of the body as it is from the cloud of unawareness that stems from its being taken for granted, so familiar is it to us. Without trying to change anything, we are investing it with our attention and therefore, with an embodied sense of appreciation and our love. We are explorers of this mysterious, ever-changing body-universe that simultaneously is us in such a profound way and isn’t us in an equally profound way.

Connecting to Your Core Being

And when some sort of healing is longed for and remains a possibility, however remote it might seem, a willingness to reclaim the body from the oblivion of taken-for-grantedness or from narcissistic self-obsession is paramount. Working at it every day, we reconnect with the very source of our humanity, with our elemental core of being.

When awareness embraces the senses it enlivens them. We have all felt that at times, moments of extraordinary vividness. In the case of proprioception, when we truly give ourselves over to listening to the body in a disciplined and loving way and persevere at it for days, weeks, months, and years as a discipline and a love affair in and of itself, even if we don’t hear much at first, there is no telling what might occur. But one thing is sure. As best it can, the body is listening back, and responding in its own mysterious and profoundly enlivening and illuminating ways.

From The Healing Power of Mindfulness: A New Way of Being, by Jon Kabat-Zinn, published by Hachette. Copyright © 2018 by Jon Kabat-Zinn

more from jon kabat-zinn

A Meditation for Resting In Awareness

Explore this 30-minute guided meditation from Jon Kabat-Zinn to expand your sense of awareness.

Read More

The Healing Power of Mindfulness

Mindfulness: what it does, how to do it, why it works—A discussion with a distinguished panel of experts.

Read More

The Best Mindfulness Books This Year

Founding editor Barry Boyce reviews the standout books we shared in Mindful magazine this year.

Read More

How to Manage Stress with Mindfulness and Meditation

Mindfulness meditation can help interrupt the stress cycle to allow space to respond instead of react. Discover our best tips and practices to equip you with tools to navigate stress.

Read More