Why Mindfulness Belongs in the Classroom

Research shows that mindfulness skills improve memory, organizational skills, reading and math scores, all while giving kids the tools they need to handle toxic stress. Read More

On a cold March afternoon, the hallways were abuzz with chatter and giggles at Chatsworth Elementary School in Larchmont, New York. As the kindergarteners from Liz Slade’s class ambled into their classroom from lunch and recess and put their jackets and lunch boxes into their cubbies, Slade asked, “Can today’s mindful leader please come up front and begin?”

Isabella, a 6-year-old wearing a heart-clad gray shirt and polka-dot leggings, quietly took a cross-legged seat on the classroom rug facing her peers. With her palms facing up and resting on each knee, she began to tap her thumbs on each of her fingers, simultaneously repeating the words “I-am-calm-now” with each tap. Without hesitation, each of Isabella’s classmates, along with their teacher, followed their mindful leader, tapping their thumbs and saying “I am calm now,” gently lowering their voices after each repetition until the room grew quiet. Slade then asked her students to slowly make their way to their tables and take out their “feelings” journal.

“They are learning the experience of settling their body,” said Slade. “What used to be a wild time now becomes a charming, sweet moment when we all take a pause and come back to being present.”

Chatsworth is one of thousands of schools across the country that is bringing mindfulness into the classroom. Growing numbers of teachers, parents, and children are reaping the benefits that learning mindfulness—defined by Jon Kabat-Zinn as “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally”—can bring, including reduced levels of stress and anxiety, increased focus and self-regulation, and improved academic performance and sleep, among others.

Children today are faced with an unprecedented amount of stress and anxiety—25% of 13- to 18-year-olds will experience an anxiety disorder according to the National Institutes of Mental Health.

With heightened academic pressure trickling down to kids as early as kindergarten, resulting in less time for play and the arts, children today are faced with an unprecedented amount of stress and anxiety—25% of 13- to 18-year-olds will experience an anxiety disorder according to the National Institutes of Mental Health. Such early stress levels can negatively impact learning, memory, behavior, and both physical and mental health, according to theAmerican Academy of Pediatrics. Escalating stress and pressure continue into middle and high school—a survey of 22,000 high school students conducted by the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence found that, on average, students reported feeling negative emotions, such as stress, fatigue, and boredom, 75% of the time. An antidote to all this stress has never been needed more. Enter mindfulness.

Research shows that mindfulness skills improve memory, organizational skills, reading and math scores, all while giving kids the tools they need to handle toxic stress. Read More

While the implementation of school-based mindfulness programs for children in grades K through 12—such as Inner Resilience, Mindful Schools, Learning to Breathe, and MindUp to name just a few—is becoming more popular, empirical research proving the benefits of mindfulness is only beginning to emerge and more rigorous research will be needed over the coming decades. “We know very little about which programs work and what works for whom and under what conditions,” said Kimberly Schonert-Reichl, Ph.D., co-author with Robert Roeser of the recently published Handbook of Mindfulness in Education: Integrating Theory and Research into Practice, and a professor and researcher at the University of British Columbia. A 2015 study by Schonert-Reichl looked at the effectiveness of a 12-week social and emotional learning (SEL) program that included mindfulness training. Ninety-nine 4th and 5thgraders were divided into two groups: one received MindUp’s weekly SEL curriculum and the other a social responsibility program already used in Canadian public schools. After analyzing measures, which included behavioral assessments, cortisol levels, feedback from their peers regarding sociability, and academic scores of math grades, the results revealed dramatic differences. Compared to the students who learned the social responsibility program, those trained in mindfulness scored higher in math, had 24% more social behaviors, and were 20% less aggressive. The group trained in mindfulness excelled above the other group in the areas of attention, memory, emotional regulation, optimism, stress levels, mindfulness, and empathy.

Compared to the students who learned the social responsibility program, those trained in mindfulness scored higher in math, had 24% more social behaviors, and were 20% less aggressive.

Although in its early stages, research on the effects of school-based mindfulness programs is being fueled by three decades of studies on adults, which shows promise for its psychological and physiological benefits. Researchers are turning their focus to children and teens to figure out what, when, how much, and from whom the teaching of mindfulness works best. “We don’t have conclusive evidence at this point about the benefits or impacts of mindfulness on youth,” said Lisa Flook, Ph.D., associate scientist at the Center for Healthy Minds, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. “We do see the promise of interventions and trainings on outcomes related to grades, wellbeing, and emotional regulation.” In other words, the research looking at the benefits of mindfulness in education is pointing toward the positive.

“Mindfulness is a powerful tool that supports children in calming themselves, focusing their attention, and interacting effectively with others, all critical skills for functioning well in school and in life,” said Amy Saltzman, M.D., director of the Association for Mindfulness in Education, and director of Still Quiet Place. “Incorporating mindfulness into education has been linked to improving academic and social and emotional learning. Also, mindfulness strengthens some underlying development processes—such as focus, resilience, and self-soothing—that will help kids in the long run.”

No one sees the value of a child’s impulse control and focused awareness as clearly as a teacher. Liz Slade, who’s been integrating mindfulness into her classroom for the last eight years, once observed a student walk up to a tall structure of blocks being built by a few of her classmates. “I watched this little girl raise her foot to kick the blocks, take a breath and then walk away,” she said. “The kids can learn to notice distraction, self-regulate, and ask themselves, ‘What do I need?’”

Slade came to mindfulness on her own about 10 years ago, and after seeing the benefits in her own life, she started experimenting in the classroom with practices that used breathing and mindful listening. “As I became more knowledgeable, experimenting and seeing what was working, I was really impressed,” she said. “The kids verbalized to me that they felt they had tools to use to handle stressful situations, which was very moving to me.”

Recognizing the impact of her own practice and the positive effects in her classroom—and with the support of her school’s principal, a critical component—Slade went on to apply for a grant for her school to bring in a formal training program called Inner Resilience, created by Linda Lantieri, who is also a founding member of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). From there, the support and enthusiasm spread throughout the Mamaroneck School District among teachers, parents, and the administration, with the Inner Resilience training program now offered to teachers and support staff at all six of its schools, which serve 5,200 students. “The best way to implement mindfulness is in an integrated way with social and emotional learning,” said Lantieri. “If we are going to be in schools we need to make sure we are helping kids learn better, and if mindfulness can help with that, great.”

“The best way to implement mindfulness is in an integrated way with social and emotional learning,” says Linda Lantieri, a founding member of the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL)

Most experts feel that the best implementation of mindfulness involves a teacher having her own mindfulness practice or at least an understanding. “It is how they teach, not just what they teach, and if a teacher is mindful in a classroom, the kids learn to be mindful,” said Tish Jennings, M.Ed., Ph.D., associate professor at the Curry School of Education at the University of Virginia, who started a program called CARE (Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education) for Teachers. “Teachers are really under a lot of stress and we know their stress affects our kids, so supporting them is a win-win,” said Jennings. Her recent research found that teachers trained in the CARE for Teachers program felt less time urgency and were more positive and more sensitive. In addition, children were more engaged and productive.

For Rosalie Choniuk, a teacher at P.S. 94 in the Bronx, New York, learning mindfulness through the CARE for Teachers program has been life-changing. “I am a completely different person since learning mindfulness—mentally, physically and emotionally,” said Choniuk. As an ENL (English as a New Language) teacher, Choniuk wears several hats in her school, often providing coverage for teachers when they need to be out of the classroom. Before developing her mindfulness practice, Choniuk grew anxious every time she was to report to a particular fifth-grade classroom, where kids were unruly and fights often broke out. “Now when I go, instead of having anxiety, I set an intention to be calm and deal with them in a positive manner,” said Choniuk. “I see the changes in the kids, who are less reactive, and the changes in myself, and now I look forward to being in their class.”

Designing and instituting a program for mindfulness in schools is fraught with potential problems. Here’s how to avoid having a poorly-designed program. Read More

If a classroom teacher is not able to provide mindfulness lessons to their class, schools often bring instructors in from outside the school. But long-term mindfulness programs can be difficult to maintain in the classroom with this model. “With an outside person, programs can work insofar as they can train teachers to keep it up,” said Trish Broderick, Ph.D., founder of the Learning to Breathe program and a research associate at the Bennett Pierce Prevention Research Center at Penn State University. “The advantage of bringing in a program to teach mindfulness is that it can be replicated and used effectively when taught by teachers or school staff who already have a relationship with the kids.”

The Mindful Schools program prefers to call its approach an adoption—where mindfulness begins at the individual teacher level—versus a rollout, or top-down decision made by leadership to implement a new program. “We don’t mandate this for all the teachers; we let it grow organically,” said Camille Whitney, former head of research at Mindful Schools. “We encourage any number of people to take the course voluntarily, and encourage it as a group so they can practice and build a program together.”

Integrating mindfulness into a health and wellness curriculum is another alternative for implementation. “Rather than adding on, a program can be supplemented into an existing program,” said Broderick, whose Learning to Breathe program is often used as part of a middle or high school’s health curriculum.

Last winter, Annie Ward, the assistant superintendent for curriculum and instruction for the Mamaroneck Union Free School District, wandered into a high school health class during a school visit. Ward was struck to see the students sitting quietly with their eyes closed and feet on the floor, as they listened to a guided meditation the teacher was playing on a CD. “It was great to see this meditation happen with no fanfare, watching the kids settle right into it and seeing that it was clearly a ritual,” said Ward.

When teaching mindfulness is accepted and embraced, it can change the tone and tenor of an entire school, or district. In 2008, the South Burlington, Vermont, school district began an effort to train teachers and students, using the Inner Resilience program for younger grades, and the Learning to Breathe program for older ones. For two years, almost 130 teachers volunteered to take the mindfulness training, and the program continued to grow and expand more deliberately to include cafeteria staff and bus drivers, totaling 170 trainees.

On top of the school-wide effort, they also invited parents to participate by offering evening mindfulness classes and lectures by local experts and visiting instructors, and in some cases, regular updates from teachers on mindfulness activities in the classroom. Training the teachers before the children and parental involvement were two components integral to the success of the South Burlington district’s efforts, according to Marilyn Neagley, former director of Talk About Wellness, an initiative dedicated to funding and developing programs for youth and family wellness.

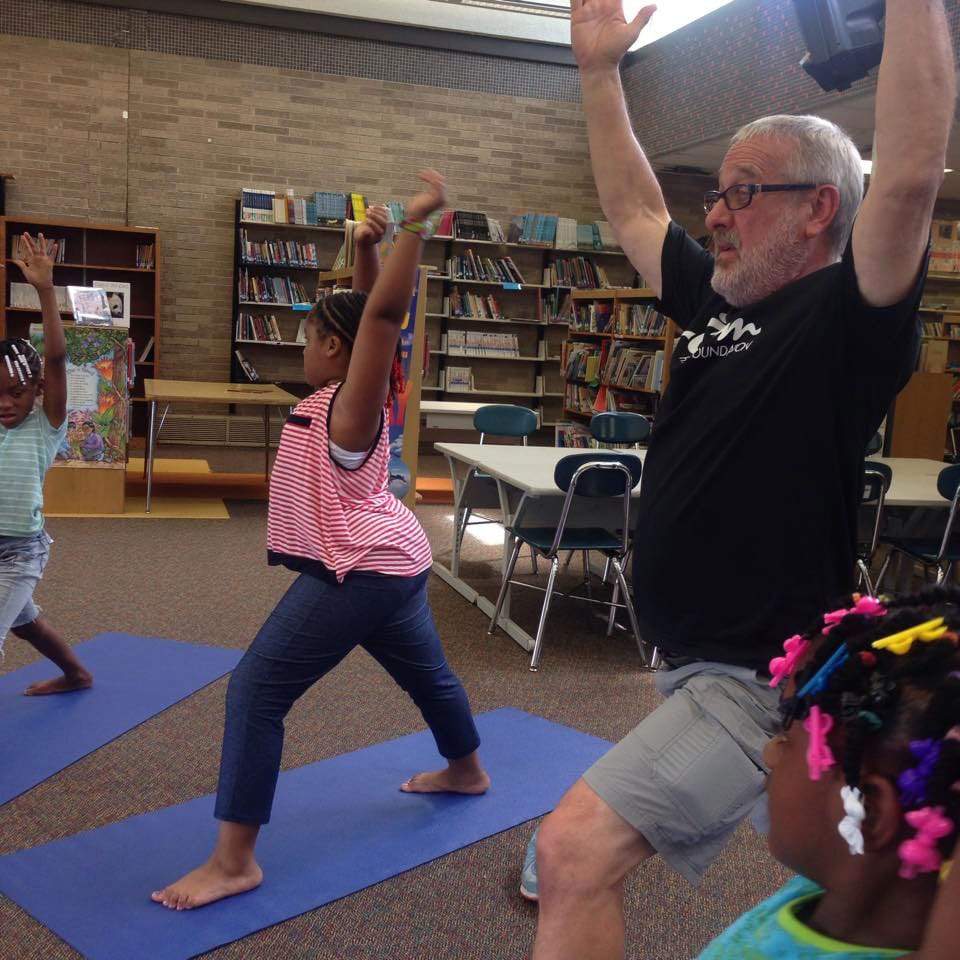

Including parents when a program is introduced is a way to expose them to what mindfulness is and is not. And then there’s the questionable connection to religion, which can, in some communities, be a hot topic. “One of the most important things we learned from public meetings with parents and the community was to be sure the training is completely secular with no religiosity at all,” said Neagley. The teaching is based entirely on emerging neuroscience and keeping all references to Buddhism, and words commonly used during yoga, such as namaste, out of the school vernacular is critical. In some schools, the word yoga has been replaced with “mindful movement” so there is no confusion about the ways in which mindfulness is being taught. “What we are teaching is how to pay attention and be more aware, and how to implement that awareness in our lives,” said Lantieri. “What we are teaching we teach in a secular context.”

One of the most important things we learned from public meetings with parents and the community was to be sure the training is completely secular with no religiosity at all,” says Marilyn Neagley, former director of Talk About Wellness.

For systemic change to take place in a district—as it did in South Burlington—administration and teachers need to figure out where mindfulness can fit, how it will work, and what is needed to bring it in. And there needs to be a point person who can move it forward. “Any district I’m working with has a superintendent or assistant superintendent who is thinking five years out, not just about one classroom,” said Lantieri. “That’s how SEL started, with one teacher who got excited.”

After journaling time was over, Liz Slade’s kindergarteners gathered again on the rug to do some imagination breaths. Going around the circle, each child paired a breath with a made-up hand movement and named it—a snowflake breath, a jellyfish breath, a clamshell breath—and the rest of the class mimicked the movement. After a while, when the kids got antsy, Slade asked them to get up and jump around. There were wiggles and tumbles and twists and then she said, “Now make a mindful statue.” The children froze in place, and all you could hear was the sound of their breath.

Teachers and parents can help kids regulate, shift, and stabilize their energy and mood, allowing for a little more silence and a little more focus. Read More

Here are four ways you can help teens to develop greater self-awareness—and ultimately enhance their sense of status and respect among peers and adults. Read More

What went well today? Kids and teens can explore this eight-minute guided meditation for noticing the positive. Read More

Try this mindfulness practice the next time that mean inner voice pops up and starts making parenting harder than needs to be. Read More

The glitter jar represents the mind settling. It’s a great afternoon activity that your kids can keep coming back to as a mindfulness practice. Read More

By Susan Kaiser Greenland

When children and teens practice appreciation painful thoughts and emotions sometimes show up. As parents we often want to ease our children’s pain, but children can easily misinterpret guidance to be thankful as an indication that we’re minimizing their challenges, even when that’s not the case. So how should we help when painful emotions do come up? We should encourage kids to view how they feel through a wide lens, not to gloss over their feelings or push them aside. When kids acknowledge their hurt feelings and remember the good things in their lives, they embody an open mind. There’s a practice I like to do called Three Good Things that gives children a chance to practice this holistic mind-set when they’re upset and they need it the most.

When faced with a disappointment, we acknowledge our feelings, and then we think of three good things in our lives, too.

The more families carve out time to practice appreciation when life is good, the easier it is for parents and children to be thankful for the good things in life when times are hard.

At first, appreciation and thankfulness may feel like a mere intellectual exercise. Yet the more families carve out time to practice appreciation when life is good, the easier it is for parents and children to be thankful for the good things in life when times are hard. When that shift happens, appreciation becomes an integral part of a family’s worldview and is no longer just an intellectual exercise.

This article was excerpted from Mindful Games © 2016 by Susan Kaiser Greenland. Illustrations © 2016 by Lindsay DuPont. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.

What can you do to bring mindfulness into your child’s school? What are the best strategies, practices, and resources to implement a mindfulness program? Implementing a school-wide mindfulness program can take several years, so create a well-thought-out plan that includes presenting programming to parents and faculty. Be patient—making changes in schools can be a lengthy process. Here are a few things to consider:

1) Kids are stressed.

2) Teachers are stressed.

Studies show that the benefits of mindfulness may include:

There are a variety of programs you can consider recommending to teachers and administrators, or for your own training. Some are online, some use recordings, and some may require in-person training. Here are a few to consider:

High School Dean and Director of Integrative & Co-curricular Learning

Grace Church School • New York, New York

As the 12th grade dean at the Grace Church School in Manhattan, Alan Brown sees his share of stress among students. And as a teacher with mindful education training, he has the methods to help alleviate it. “There’s a lot of difficult conversation that comes through my office, and to be the non-reactive, compassionate presence in the room with students, parents, and colleagues who are worried or sad has been a real game changer.”

Brown has brought mindfulness into his school on multiple levels, including a semester-long elective that meets twice a week for 10th, 11th, and 12th graders (and fulfills an academic requirement), an intensive eight-week course, a mindful movement class, parent workshops, and soon, a faculty cohort. “As a dean, my priority is to provide kids with a tool box,” said Brown. “I know what challenges are coming, like the ones they’ll face in the fall of their senior year, and I want them to have the tools when they get there.”

“When you work with children, it’s really easy to ignore our own needs,” said Brown. “Mindfulness has given me a greater sense of balance and calm, which is a benefit to the other people around me.”

Principal

Bessie Nichols School (K-9) • Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

“Practicing and teaching mindfulness to kids is the best job-embedded professional development one could ever have,” said Doug Allen, a school principal who completed a mindful educator certification program in 2015. Within two years, Allen has implemented a school-wide mindfulness program—consisting of 16 lessons over 8 weeks—to three-quarters of the school’s 1,100 students, and the remaining quarter will go through the program by the end of May. His enthusiasm quickly caught on, and 30 teachers have followed suit, taking mindfulness courses for both their benefit and that of their students.

Although Allen previously had his own meditation practice for many years, teaching mindfulness to kids took it to another level. “It changed my relationship with my students and my work, and I really came to believe I was doing something more lasting and meaningful than I had before.”

In addition to teaching mindfulness in the middle school, Allen gets to see the benefits all around the school building. One 9th grader told him she was going to do mindful breathing before taking her driving test (she did and she passed), and on another occasion, a teacher reported that while two girls were explaining their sides of a heated argument, one said she needed to practice her breathing so she could calm down and give her explanation. “I’ve been teaching for 27 years,” said Allen, “and mindfulness has really provided me with a greater sense of purpose in what I do.”

Math Teacher & Mindfulness Coordinator

McLean School • Potomac, Maryland

Recently retired after 30 years as a math teacher, Rosie Waugh continues teaching part time in her role as Mindfulness Coordinator at the McLean School. Last summer, she completed her mindful educator certification, and has been part of a team of McLean School teachers and administrators who have implemented a school-wide mindfulness program. In addition to structured lessons, every six to eight weeks the school features a theme—such as heartfulness, emotions, or listening—and the entire school participates, decorating bulletin boards and posting cards around classrooms.

“It all started about four years ago with one parent who introduced mindfulness to us teachers,” said Waugh, “and it helps having the head of our school so committed.” In her new role, Waugh also runs a mindfulness club and sometimes brings some of the 7th grade boys to speak about mindfulness with the elementary school students, and explain how to use a glitter jar. “Engaging the kids really keeps it vibrant, interesting, and fun,” she said.

“My practice is always evolving, and the kids I work with know that sometimes I need to stop and take a minute for myself,” said Waugh. While it’s a little trickier teaching high school kids, Waugh says they are respectful and know they don’t have to participate but they need to cooperate. “They’ll tell me they know it helps them, on the sports field or remembering lines in a play, and I’m glad they have a skill for when they just want to have a little space.”

Mindfulness Instructor

Daniel Warren School • Rye Neck, New York

On a recent visit to the Daniel Warren School, where she’s a visiting mindfulness instructor, Cheryl Brause entered a second-grade classroom, sat down, and made eye contact with the children who settled on the floor in front of her. “Instead of feeling the need to tell them what to do, I could simply acknowledge them one by one, silently welcoming them into our time together, and this let them know that I am here to listen and to be present with them as we explore mindfulness together,” said Brause. As her own practice and knowledge deepened through a yearlong mindful educator certification that she completed this summer, Brause recognizes the changes in her experience. “I’m much less distracted while teaching, thinking less about what I need to accomplish, and more present and focused on the kids, allowing the lesson to flow from there.”

Brause came to mindfulness as a means to slow down and be more present in her own life. It began with a yoga practice, and after trying a variety of types of meditation, it was an MBSR class that exposed her to mindfulness. “I realized how quickly mindfulness resonated with me and made a real difference in my everyday life,” said Brause. “It made me realize how distracted I had been and how little time I spent being fully present.”

School Librarian

P.S. 10 • Brooklyn, New York

According to Joanie Terrizzi, a school librarian, mindfulness hasn’t changed her life—it’s changed the way she approaches it. “I see up to 200 kids a day, and mindfulness has helped me navigate distractions and demands so I can give kids the rare gift of my full attention,” said Terrizzi. “I knew my practice was having an effect when a student was doing something I didn’t want him to do, and I turned to open my mouth and instead of my stricter teacher voice, something very soft and calm came out.”

Once she completed her yearlong mindful educator certification in 2014, Terrizzi began to incorporate mindfulness into the library curriculum. Each week when the teachers dropped off their students at the library, Terrizzi would teach a mindfulness lesson, routinely beginning the library class with ringing a chime and mindful listening. “I expected the kids to be resistant but they weren’t and it slowly began to change the tone of the whole school,” she said.

Terrizzi collects quotes from the children who share their experiences with mindfulness, and hopes to turn them into a book one day. “Before I started the mindfulness training, I had severe burnout and was completely drained,” said Terrizzi. “The content and perspectives I learned changed everything, and re-enlivened my approach to children and education.”

https://vimeo.com/350987136 So much of communication is actually not about what we say. It’s about how we come across, the tone of our voice, our body language, and all of that is an expression of our internal state. So this is one of the reasons why mindfulness is such an essential… Read More

https://vimeo.com/350989097 If you’re trying to bring this into a school, or into an organization, you find the person most likely who’s going to be open to it, and you start there. Maybe, you just start in that one classroom. Find a Mindfulness Ally I have a friend, she’s a nutritionist… Read More

A free resource offering the best practices for bringing mindfulness into the classroom from 25 of today’s leading mindfulness experts and educators. Read More