When I woke up on the morning of September 28, 2011, I had no idea that this would be my wedding day. John had been invited to a MacArthur Foundation event in Paris, an international mind-meld of twelve academics from different fields who all had something to contribute to the study of aging. The group included some of the world’s top public-health experts and psychologists—among them my fiancé, John Cacioppo, one of the founders of social neuroscience, most famous for his pioneering work revealing the mentally and physically damaging effects of loneliness. John was invited to discuss, among other things, how the elderly could protect themselves against the dangers of loneliness. At the time, he and I were several months into our long-distance love story and getting good at juggling business and pleasure.

John suddenly looked very serious. “No, I’m meeting someone over there, someone important.”

He started to tell Laura about me, how we had fallen for each other after a chance encounter in Shanghai, how he needed to be on that flight. Laura knew about all the wreckage from John’s two divorces. It struck her that John spoke about me as though I was his last chance at love. He said he wanted to get this one right.

Now, in Paris, Laura wanted an update: “How are things with Stephanie?”

A sheepish grin. “We’re getting married.”

“Wow, John, that was fast! Congratulations! I’m so happy for you. When is the big day?”

He looked momentarily confused.

“Oh, I don’t know if we’ll do a classic wedding. Steph and I are both so busy. We’ll probably just go down to City Hall in Chicago during our lunch break.”

“You know, I could marry you right now.”

Laura had just gotten ordained as an internet minister to officiate the wedding of one of her grad students. She meant her suggestion purely as a joke—“There was not a shred of seriousness in it,” she later told me—but John didn’t seem to realize this.

“You mean, like, today? You know, Steph’s here in Paris with me… That could actually work!”

He grabbed his phone and began typing a message to send to me. DO YOU WANT TO GET MARRIED AFTER WORK TODAY?

“John, wait—what are you doing?!” Laura said. “Are you crazy? These things must be planned out.” John didn’t seem to be listening. The conference was about to resume. Laura just shook her head and muttered under her breath, “John, you don’t know women.”

He smiled devilishly. “You don’t know Steph.”

So, did I want to get married today? I did a double-take when that message flashed on my phone. But it only took me two seconds to reply. “Sure.”

Then I dashed out of the hotel room to find a white dress.

Turning Your Back on the Frontal Lobe

By surprising me, John had instantly found a way of making our wedding special and unique, however it turned out. Such a spontaneous ceremony wouldn’t work for everyone, of course, but it’s worth considering the role that unpredictable events might play in love, and whether we can benefit by making more room for improvisation in our relationships.

So much of our social experience, especially when it comes to romance, has to do with expectations. Maybe we have an image of the man or woman we will marry long before we’ve met them. Usually, we call this a type, an ideal. Or maybe we have in our mind’s eye the perfect first date: a walk by the lake, a hike in the woods, a romantic restaurant. When it comes to the wedding—an opportunity not only to proclaim our love but also to show off our good taste and social network—we probably know how it should look. Perhaps more importantly, we know how it should not look.

If these expectations actually set us on a course toward genuine happiness, then they are all well and good. But I would argue that in many cases such plans can become a kind of mind trap, forcing us to pursue a preconceived kind of happiness that we may never reach or that, once reached, may not actually make us happy. To take just one study proving this point, the Yale psychologist Robb B. Rutledge and his colleagues conducted an experiment in which they had participants set expectations before playing a decision-making game with small financial rewards. Their results show that the ultimate amount of money participants won did not determine their happiness. Rather, what predicted their level of happiness was the difference between their initial expectations and the outcome. If they had no expectation of winning and ended up with even a tiny amount of money, they were happy.

Social pressure often drives us to pursue unrealistic expectations, without understanding what it is we really want or need.

Applying this expectation formula to love relationships, the more we love without expecting any rewards in return, the more we will increase our chance of happiness. This is in line with a large body of research showing that setting realistic expectations leads to greater relationship satisfaction. But adjusting your expectations does not necessarily mean lowering them. It’s more about letting go of the social pressure that often drives us to pursue unrealistic expectations without understanding what it is we really want or need, and what we can do without.

The important thing about letting go of your expectations is that it should feel like an act of generosity or faith in your relationship—and not a sacrifice. Otherwise, you will likely feel that you’re giving up something important to you for the sake of your partner, leading to feelings of resentment or spite, which can spell serious trouble. An interesting study from the Netherlands shows that while couples greatly appreciate it when their partner makes sacrifices for them, when they begin to expect such sacrifices they feel much less gratitude and no longer see their partner’s sacrifices in quite the same positive light. This finding is in line with a theory I’ve long held: Expectations kill gratitude.

We have a natural tendency to expect help, support, and sacrifice from our partner to some extent, but the beauty of our evolved brain is that we are neurologically wired to control this tendency and, if so moved, to expect less from our partner and give more in return—intentionally. The next time you have romantic dinner plans with your partner but they feel “brain-dead” after, say, an entire day of back-to-back Zoom meetings, ask yourself what’s more important: sticking to the script you had for how that evening should play out, or letting it go for both your partner’s sake—and your own. You might discover that going to bed early and spending the night cuddling under a warm blanket or stargazing together from the comfort of your backyard was actually more romantic than whatever elaborate evening you had planned.

What You Expect Is What You Get

Expectations don’t only complicate life within a relationship, they also can get in the way of connecting

with someone in the first place. What if you find the “One” but you don’t recognize that person as such because you had a different idea of what the person you marry should look like? Conversely, what if you stay in an unhealthy or abusive relationship for too long because you and your partner should be perfect together, because on paper your partner is the kind of person who should check all your boxes? Sometimes the search for that perfect partner can make someone go to extraordinary lengths. Such was the case with Linda Wolfe, an Indiana woman who married 23 times—earning her a place in the Guinness Book of World Records—but who never found Mr. Right. Shortly before her death in 2009, she said she was still holding out hope that husband Number 24 would come along to fulfill her dreams.

These dreams, hopes, expectations, and scripts we write for our future, which play out over and over in our minds, are managed (in part) by the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Considered for decades a mysterious brain area, the PFC is now seen by many neuroscientists as one of the parts of the brain that make us most human. Located smack in the front of the cerebral cortex, it contains some of our newest hardware, evolutionarily speaking. Its large size and extensive connections with a diverse pool of neighbors enable it to contribute to a broad range of mental functions, including decision-making, language, working memory, attention, rule learning, planning, and the regulation of emotions, to name just a few.

I sometimes describe this region as the brain’s “parents,” telling you what you should and shouldn’t do. The processing that occurs in the PFC is the closest thing we have to Freud’s notion of a “superego.” This part of the brain helps us distinguish right from wrong, control and suppress urges, see silver linings in dark situations, and forces us to make hard decisions and delay gratification, if it benefits us in the long-term or benefits some cause greater than ourselves.

It is a little-known fact that humans don’t have a fully mature PFC until about age 25. This explains why you might have done things at 18—a keg stand? a tongue piercing?—that you would never have done a decade later. Yet as much as we need the PFC in order to be functional and responsible adults, there are times when we want to reconnect with our younger selves, not to second-guess our actions so much, to think less about the future and more about the now, to be in the moment. I think often about the French poet Charles Baudelaire’s definition of genius: It’s nothing more than “childhood recovered at will.”

I love this idea. And when I am truly living in the moment, this is how I see the world, with the joyful curiosity and sense of wonder that children possess. This is not, however, an invitation to impulsive behavior. We don’t want to completely turn off our PFC. That would be a disaster.

If we did that, we would be ruled mostly by our impulses. We would lose a grip on and lack the ability to regulate our emotions, to manage psychological pain, and to complete tasks we had scheduled for the future. We would end up looking at the world less like children, who are eager to learn and discover new things, and more like patients with a lesion, a tumor, or a disease affecting the front part of the PFC (known as the orbitofrontal region). Such patients exhibit a lack of impulse control, have difficulties in meeting personal and professional responsibilities, and make all manner of social faux pas.

While the PFC is essential to our social nature, sometimes we let it control us too much. Studies show that rumination, recurrent negative thinking, self-focused thinking, and even obsessive-compulsive disorders are associated with changes in the PFC. The prefrontal cortex on overdrive is not a pretty sight. We think less flexibly, we obsess over minute details, make ourselves sick with worry, turn something over and over endlessly in our head. In such cases, we are trying too hard to stay on script, to anticipate what will happen, to plan and perfect.

This kind of PFC-driven overthinking can at times be a roadblock to creativity. When neuroscientists zap parts of the PFC to reduce its influence (using a noninvasive technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS), we find that people show a cognitive enhancement as they are better at solving problems or brain teasers, and tend to think more outside the box. With mental training, we can achieve similar results, whether that means coming up with a solution to creative problems at work or finding a way of turning a scientific conference into an impromptu wed- ding party. Not only are we more creative when the PFC is kept in check, we’re also in a better mood. Studies show that the less we ruminate, the higher our subjective measures of life satisfaction and happiness are.

The Joy of Missing Out

So the question then becomes: How do we keep the PFC in balance? How do we benefit from all its useful aspects—the way it helps us plan, save, and control unhealthy or harmful tendencies—without letting it rule our life, causing overthinking, anxiety, and other problems? In other words, how do we go off-script? How do we say no to FOMO, the fear of missing out, and say yes to JOMO, or the joy of missing out?

Popular antidotes to combat negative overthinking include meditation and mindfulness exercises. Such techniques have in recent years gained in scientific credibility. Two of the people who helped change attitudes toward meditation and mindfulness are the American neuroscientist Rich- ard Davidson, a master in mind-body interactions and a pioneer in the art of reining in the PFC, and the French Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard, a master in finding wonders in solitude and strength in self-introspection. Together they have formed a friendship and collaboration with the Dalai Lama. They have conducted experiments in Davidson’s laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (and in other laboratories around the world) in which they used EEG and fMRI to study the brains of Tibetan monks and other students of meditation. Their results show how highly trained practitioners (with over 9,000 hours of lifetime practice on average) can control negative thought processes, accept every feeling as they come in a nonjudgmental way, and modulate the activation of various brain areas, including the PFC—the region which, as Professor Davidson elegantly described, is “absolutely key” in emotion regulation, as the PFC is “a convergence zone for thoughts and feelings.”

Yet it’s not only eminent monks with years of training in meditation who can benefit from such techniques. In 1999, Davidson and his colleagues contacted the CEO of a biotech company and suggested that he teach his employees mindfulness meditation and then assess how it might affect some measures of physical and mental health. Forty-eight employees volunteered to take part in nonjudgmental moment-to-moment awareness training, which is also known as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (or MBSR). Every week for two months, the employees participated in a two-and-a-half-hour session. The researchers measured the volunteers’ brain waves (focusing on the PFC) before and after the training period. At the end of the eight weeks, the results were clear. Compared to a control group, MBSR volunteers showed a 12% drop in their anxiety symptoms and a shift from right to left PFC activation. Interestingly, the PFC in the right hemisphere of the brain tends to process negative emotions, whereas the left PFC specializes in positive emotions—an indication that the mindfulness training was working.

Being in the moment can quite literally clear the mind of unwanted and unnecessary negative thoughts and replace them with more constructive thinking.

There are now numerous mindfulness apps and behavioral therapies that can help ruminators become meditators and gain new insights not only into their physical and mental health but also into how their brains function. In time, they can learn to suppress the impulse to obsessively focus on negative past and negative future events, putting the PFC in a more peaceful place. What mindfulness practitioners find is that being in the moment can quite literally clear the mind of unwanted and unnecessary negative thoughts and replace them with more constructive thinking. Such intentional change in mindset will open you up to experiences that may be richer, deeper, and more meaningful than anything you could have ever planned or ever imagined.

Finally, nature has also been shown to have a potent effect on reducing rumination and regulating PFC activity. For instance, a 2015 study performed at Stanford showed that participants who went on a 90-minute walk through a natural environment showed reduced neural activity in the parts of the PFC that foster rumination.

Celebrating the Spontaneous

Before that day in Paris, John and I had been falling deeper and deeper in love—but rumination had started to kick in. There was one big biological fact separating us: our ages. John was 60. I was 37. And he worried whether marrying a much younger woman was a good idea. I don’t think he cared about what it looked like, the assumptions some people would make based on their own scripts for a “proper relationship.” I don’t think he was thinking about himself at all. Rather he was worried about me.

If something happened to him, I would be alone, and, much worse from John’s perspective, I would be susceptible to loneliness. John knew, perhaps better than anyone on the planet, what loneliness could do to a healthy brain. And he was sensitive to the actuarial reality of our circumstances. If we tied the knot, odds are he would not be around to celebrate my 60th birthday.

“We may be in love, but we haven’t committed yet,” John said. “We’re still on the outside of this. I know, because I’ve studied it, the kind of loneliness that overwhelms a widowed spouse. The idea that you could live with that for decades—I can’t in good conscience put you in this position.”

I’m stubborn. I told him to forget it. I told him that I could never let something as seemingly trivial as age dictate our love. Looking back, I can’t help but think that it wasn’t only our age but also our academic specialties that influenced our positions. I was arguing for the joyful power of love, and he for the destructive power of loneliness.

We decided to take a week away from each other. No phones, no Skype. Some emotional distance. I went exploring caves with a girlfriend in southern France. And he went on vacation to Peru. We both spent our trips going through the motions of having fun, trying to distract our- selves from the fact that we missed each other so much it was hard to breathe. At the end of the week he sent me a photograph of his left hand. He had put a silver band on his ring finger. “I’m yours,” he wrote.

How often is happiness destroyed by preparation, foolish preparation!

JANE AUSTEN

On the day of our wedding, the whole scientific conference metamorphosed into a wedding party. We couldn’t rent a spot on such short notice, so we decided to do the ceremony guerrilla-style in a random corner of the Luxembourg Gardens, near our hotel. John asked Dr. Jack Rowe, a professor of public health at Columbia, to give me away. (“But I haven’t even met the bride!” Jack said.) Laura would officiate. The hotel chef whipped up a wedding cake with just a few hours’ notice. The University of Pennsylvania sociologist Frank Furstenberg, armed with his iPad, served as our photographer.

As John and I stood there, united in our love, I found myself looking at the people around us, many of whom I had only just met. They were beaming. None had expected to end up attending a wedding, but each played a role in the affair, each felt a sense of taking part in something special. Both our spontaneous wedding ceremony in Paris and our official wedding in Chicago two weeks later remain two of the best moments of my life, but I have to confess, in my deepest heart, I feel like our spontaneous ceremony marked the first day when John and I became man and wife. In holding romantic expectations lightly—our own, and those of the people around us and society generally—we were creating space for all the unusual and marvelous qualities of those moments and, really, of our connection.

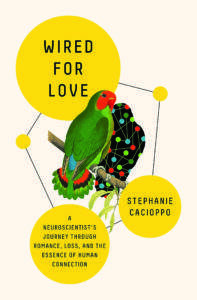

Excerpted from Wired for Love: A Neuroscientist’s Journey Through Romance, Loss, and the Essence of Human Connection.

Copyright © 2022 By Dr. Stephanie Cacioppo. Excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books, a division of Macmillan Publishers. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

READ MORE

A 10-Minute Practice to Help Curb the Habit of Gossiping

Try this guided mindfulness exercise to help you change the habit of gossiping. Next time you feel the urge to gossip, you’ll be better equipped to stay aligned with your integrity.

Read More

The 4 Qualities of a Good Listener

A good listener not only focuses on your words, but what’s on your mind. Do you have the following qualities of a good listener?

Read More

How to Strengthen Loving Relationships with Mindfulness

Our guide to reflecting on the relationships in your life and opening yourself up to the opportunity for love to grow.

Read More