Listen to “Where Does the Path of Mindfulness Lead?”

In my experience most people who start practicing meditation find it, at first, to be an unusual or unnatural experience. Asked to sit still and pay attention to our breath repeatedly, most of us will formulate some version of the thought,

“Why would I do this?” and after a little while,

“Why would I keep doing this?”

It feels like an artificial, contrived activity.

“I don’t want to do this anymore. What’s the point? I could be doing something productive,

or enjoyable. On top of it, I’m no good at this.

I can’t do it.”

If it were a TV show, we would change the channel; a conversation at a party, we would move along; a concert, we would leave at the intermission, and maybe never buy a ticket for the band or orchestra or singer again; a website, we would bounce. I have indeed seen people leap up very early in the proceedings and leave for good. One guy stormed out, proclaiming,

“This shit is stooopid.”

In point of fact, we are not wrong about the strangeness. The standard instruction for mindfulness meditation is artificial. It’s an artifice, a technique to gradually—or possibly in a sudden flash—bring us down into where we are. Paying attention to our breath is pointless and unproductive, and yet that is the very point.

We need to be tricked into not escaping from where we are. We like to have tasks, so when given the task of continually anchoring our attention to something very simple, we want to get it right, but what the simple meditation instructions really do is reveal to us our repeated desire to escape where we are—thinking that the grass is indeed greener somewhere other than where our body and mind are at present.

As we notice how trying it can be to pay attention to the simplicity of the moment and how unceasing our stream of thoughts is, we come to see the contrast between being lost in thought and being fully engaged with where we are and what we’re doing and feeling. We may think it’s a battle between the breath and our thoughts, but that’s a battle we will never win. Seeing the contrast is the point, so we stop being so concerned about all these thoughts. It takes some of the seriousness out of them when they become like passing clouds.

Over time, the focus on meditation technique can indeed recede a bit, and when we practice meditation, we develop a sense of presence that doesn’t need quite so much maintenance. But the straightforward technique is always there to fall back on in times of great stress and distraction—even crisis.

One of the early (and ever-present) challenges in practicing meditation is the very human characteristic of having goals. Having an aim and a purpose is essential to most everything in life. If you set out on a trip, you need a destination. When you make a meal, you have a plan for how it’s going to turn out. If you’re in business, you want the business to succeed, so you have lots of goals.

But goals become very tricky on the path of meditation. I use the word path, because it is an unfolding journey, but if you try too hard to be the boss of where you’re going, with too many expectations, the road will be rockier. It’s like trying to control the destiny of a child or a partner. There are simply too many causes and conditions determining what happens next. The path of meditation, the arc as some say, is not a straight line. It’s about lots of ups and downs, ins and outs.

Paying attention to our breath is pointless and unproductive, and yet that is the very point. We need to be tricked into not escaping from where we are.

The path of meditation rewards patience, and a willingness to adapt to what emerges next, and to be honest with oneself when hard truths surface. Meditation is not something that occurs outside of life circumstances (pain, illness, financial difficulties, loss, etc.). On the contrary, by asking us not to escape from where we are, meditation plunges us straight into the vicissitudes of real life, along with any baggage we may be carrying. So much for the primrose path of mindfulness.

The Heart Calls to You

What will inevitably come to the fore as we spend more and more time sitting with ourselves—becoming familiar with the texture of our mind and what lurks within—is emotion. In contrast to a simple perception (of heat or light, say) or an abstract thought (like, There goes a cat), emotion carries lots of energy and color. It manifests throughout the body and it can repeat itself, taking the shape of a mood. What begins as anger can develop into a highly irritable mood state. In the same way, a moment of happiness can blossom into a cheery mood. (If our moods are intensely anxious or persistently dark, we may need to seek clinical treatment.)

I have known no meditator who has stuck with the practice for whom the emotional landscape has not become an area of intense interest and curiosity. It’s not something you sit around idly thinking about, though, or wring your hands over. It’s something you sit with, time and again, seeing up close the life cycle of an emotion. You are getting to know yourself now in a very intimate way. The bit of stability gained from basic attention practice (usually anchoring on the breath) allows you to probe more courageously into your emotional terrain. When you find it too intense, you can see the need to fall back on cultivating your attention more. And if you do so, you may be able to probe further. It becomes a virtuous circle, more attention leading to deeper probing to more attention, and so on. We alternate resting and probing.

The fruits of meditation emerge as byproducts, while you’re not looking. If you try with great pressure to calm yourself and even to be kinder to yourself and you push and push, your goal will likely elude you. It’s as if you are a gardener trying to will a tomato into existence. If you water the plant, and attend to enriching the soil, and you’re fortunate enough to get enough sun, the fruit will emerge. Voilà! One day, you are suddenly picking ripe tomatoes. In meditation, it may be someone else who first notices that you’re a little less stressed, that you are reacting less dramatically to bad circumstances. Did you make that happen? It emerged from just being there, which quietly leads to less focus on me, me, me. That’s the real mark of progress, the fruit, the beneficial byproduct: less me.

The bit of stability gained from basic attention practice (usually anchoring on the breath) allows you to probe more courageously into your emotional terrain.

The notion of less me raises an inevitable—and highly reasonable—set of questions, such as does this mean utterly lacking in personality, a big part of what makes life fun? Or, if there’s less me, how do I figure out how to take care of myself? What about my passions, wishes, desires—do these all go by the wayside?

Short answer to all these questions: No.

It is devilishly hard to describe, and best understood as a way of being that accrues over time with experience. It means less firmly gripping to the part of ourselves that constantly seeks security and attention, rather than resting in confidence and faith that life is ultimately workable and that we are OK as we are. Less take, more give. Less self-serious, more carefree. More heart, less head. Your pain and your plight is not of paramount importance. Everyone’s pain is of paramount importance.

Widening Your Scope From Within

Meditation is one of those aspects of life that rewards an amateur’s approach, in the original sense of the word, an amator, one who loves. We do it not to become skilled, proficient, or professional, but out of a growing passionate curiosity about the nature of our mind. It rewards a beginner’s attitude, a willingness to not know and to see oneself as a perpetual student. So, in some sense, the middle of the path of meditation is more beginning, more opportunities for less me.

In seeking to find those opportunities, though, we may also find ourselves wanting to share what we’re doing with more people—both in terms of introducing people to mindfulness practice and finding fellow travelers and guides. When you’re committing to this kind of uncommon inner exploration, it sure helps to have company. Mindfulness is extremely uncommon in the day-to-day world. So many things you encounter are trying to lure you into an experience that distracts you from being with yourself. With meditation, you are intentionally going inside and not hiding from what you find there. It’s nice to have friends, then, including ones with more experience. It can get lonesome. There be dragons within.

As we explore less me, we may also try to adopt more practices and put structure into the ways we weave practice and life together. In general, we reach in more, as well as up and out.

Reaching in more can take the form of periodic longer sessions of meditation. And if anything can be said to mark a transition from the beginning of the path of meditation to the middle, it’s breaking through the restlessness barrier and finding the simple ability to be with oneself longer without running away. This ability becomes the doorway to deeper exploration, both on your own and with others.

Eventually, inevitably, the point of mindfulness becomes how we relate with other people. Some people define mindfulness as close, focused attention, and define awareness (or panoramic awareness) as attention that takes in a greater scope, more of our surroundings, and more of what’s going on with others. At times, we need a tighter focus to rein in our wild mind; at other times, we can be looser and more expansive.

If anything can be said to mark a transition from the beginning of the path of meditation to the middle, it’s breaking through the restlessness barrier and finding the simple ability to be with oneself longer without running away.

Our early explorations into our emotions may lead us to recognize a need to be, first, kinder to ourselves, and then to extend that kindness to others. We are motivated to do so because our mindfulness practice has likely put us in deeper touch with our pain and the pain of others. To the extent we have found relief, we want others to find that relief. It’s a gift we’ve received that we simply are bound to share with others. Our generosity may take the form of an actual material gift, ongoing encouragement, or the gentle suggestion to try some mindfulness.

Our reaching out may also take the form of applied mindfulness, which may be personal (like mindful parenting or deep listening) or societal (like mindful education or leadership), or a combo of both—the lines are not hard and fast.

Deepening Your Dive

As we reach up (developing more meditative skill and the byproducts of that skill) and out (connecting with more people and sharing our meditative gifts), certain pitfalls can begin to emerge. We may begin to become proud of our little meditative accomplishments. That’s the power of me creeping back in. It’s the beginning of starting to become a meditating asshole. You actually start to think that because you meditate (and/or practice yoga or whatever well-regarded beneficial thing you do), it means you are a big deal. You are not.

Another pitfall, particularly associated with helping others and cultivating kindness, is burnout and resentment. We forgot to take care of ourselves or we got caught up in the glory of do-gooding (there’s that damn me again). We hit a wall, and if we hit that wall hard enough, we can even be traumatized. I have seen the path of meditation come to a dead halt for people under these circumstances: What the hell was the use of all this work on myself and on helping others if this is how I ended up?

A beneficial principle at this point is that however much we reach up and out, we also need to reach down and deepen in equal proportion. It’s like a tree. As the tree grows up and out, it also has to send down deeper roots. It finds nourishment from above and from below. Deepening, in this case, means more of the basic kinds of practices we’ve relied on from the beginning: time spent paying simple attention, noticing our emotions, being kind to ourselves, kind to others. We need refreshment and restoration, water and nutrients from the earth. This basic image of the tree has been a powerfully helpful one for me, as I learn to let go of arrogance and overextending, repeatedly. We can never stop learning that lesson.

As the economist John Maynard Keynes famously quipped, “In the long run, we are all dead.” So, what of ends? What is the end of the path of meditation like, what are the final stages?

There is no end. When would you stop cultivating peace, caring for others, love, and strength? The most I could say is to report what I have observed about people I admire who have had a very long relationship with meditation: They have a very light touch, a sense of humor, a carefree quality. While the world all around is obsessed with getting something, achieving something, getting better, they are bemused. They are compassionate, and yet they know that compassion goes way beyond being nice, that the most compassionate thing you can do is help someone to become less focused on themselves and their big ideas.

They couldn’t care less, the outcome doesn’t really matter, and yet… You feel their warmth embrace you. Perhaps there is so little me (clinging to self-centered concern) that there is virtually no me at all.

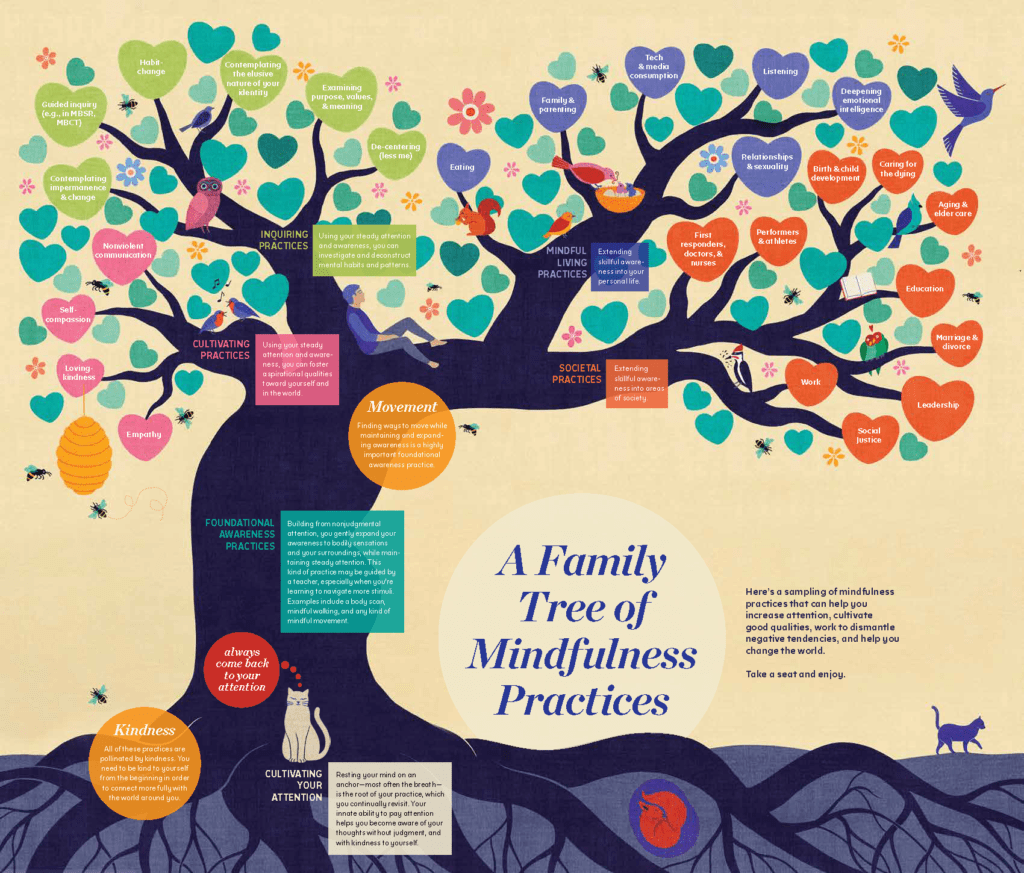

A Family Tree of Mindfulness Practices

Here’s a sampling of mindfulness practices that can help you increase attention, cultivate good qualities, work to dismantle negative tendencies, and help you change the world. Take a seat and enjoy. (Click the image below to view the illustration)

Invite Your Demons on Retreat

If you are so motivated, and your life allows it (I did little to no retreat when my children were young), it can be worthwhile to take a day or a weekend, a week, or even longer to go on a meditation retreat under the guidance of experienced teachers. It is not a sound idea to just go off by yourself for long stretches. That can lead to painful mental sidetracks. You want to be around others who know what they’re doing and can supervise your retreat time.

Retreat invites all your resistances and demons out into the open. When you see them, and you entertain them for a while, and they pass away, and come back, and pass away, and come back, and pass away, and… They begin to lose some of their power over you. Negative defeatist thoughts require care and feeding. When you starve them, they start to fade into the background. To our great relief, that’s one of the forms less me takes: less negative carping from your inner critic. You laugh at him or her. It’s like your inner critic’s pants are always falling down in public. Oops.

Read More

How I Discovered That I Wasn’t the Centre of the Universe (and Neither Are You)

While getting centred feels like a relief to those of us who are scatterbrained meditators, it can also serve as a natural starting point to explore the art of decentering and tap and elusive state of being centerless. Here, Founding Editor Barry Boyce takes us on a mindful tour of these mental vantage points.

Read More

Following the Path of Mindfulness

Mindful editor Anne Alexander invites us on the journey of deepening our sense of wellness through mindful ways of thinking and being.

Read More