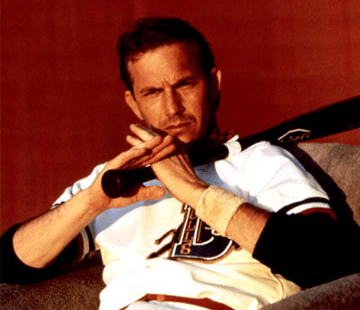

In the baseball comedy Bull Durham, a mercurial pitching prospect nicknamed Nuke LaLoosh is shepherded toward stardom by his girlfriend, Annie, and his catcher, Crash. Nuke’s career turns the corner when Annie advises wearing a garter under his uniform and breathing through his eye lids on the mound. Neither of which I’ve ever recommended to anyone myself, but both touch on a basic premise of mindfulness: Nuke is too ensnared in over-thinking everything to actually pitch well. Getting out of his churning, chaotic mental storm, aiming to attend somewhere else for even a moment, allows him to find his own capacity to act skillfully.

Focusing attention on breathing through the eyelids doesn’t change anything directly. (It isn’t even, as far as I know, actually possible.) It does break Nuke out of his mental cycle long enough to just throw. It’s a reminder most of us would benefit from in our lives, with or without continual guidance from a wise, sardonic baseball catcher and equally sanguine girlfriend.

Baseball for Care Providers

This astute advice doesn’t only apply on the baseball diamond. You are a caregiver—maybe a parent, teacher, psychologist, or doctor, and you put a lot of energy into taking care of others. And then your day gets busy, and your mind even busier. What happens when you become lost in over-thinking what you should have done, ruminating over decisions to be made, swamped by logistics, or worried about what everyone else is thinking of your performance?

Real life throws up obstacles and challenges. The paperwork or the intensity or the physical exhaustion can take over, not to mention pressure around decisions that profoundly affect the lives of others. Now the day is focused on treading water, keeping up, or getting home. Caught in the daily grind, when was the last time you found enough breathing room to settle down and think clearly again?

It’s easier than it seems to lose touch even with compassion, which is probably a feeling that led you to this position in the first place. A child, student, client, or patient is angry or scared and acts … less than skillfully. Even when logically you know better, how easy is it to remember that their challenging behaviors are probably driven by anxiety, fear, or suffering?

Meanwhile, you may feel self-judgment wanting to do something when there is actually nothing to fix, or when you do not know the answer but feel you should. You may feel self-judgment when you’re tired and burnt out, a sense that you shouldn’t feel what you actually do. The pressure to be perfect, to know everything, and to repair all can feel consuming. How often do you manage to sustain a supportive perspective towards yourself?

In Bull Durham, one idea that Annie and Crash are demonstrating for Nuke is how much of stress has to do with attention. Unsettling thoughts grab hold, our fight-or-flight brain takes over, and we stop thinking and acting at our best. Stress tends to escalate itself. Churning, unsettled thoughts and feelings lead to similar thoughts and feelings, perpetuating the experience beyond whatever triggered it in the first place. You’re worried about pitching your first game, which creates a mood, which changes how you interpret what your catcher says to you, which makes you feel even more rotten, and on and on.

Choosing to break the self-perpetuating cycle by paying attention to what it feels like to breathe allows the brain to settle. Since most of us don’t know a Crash Davis, we have to break ourselves out. Taking a moment to attend carries great benefit and does not require anything as extreme as eyelid breathing.

Getting Ready for a New Ball Game

Mindfulness is not magic. (Baseball may be, but for that watch Field of Dreams.) The mind gets busy, and our stress escalates over moments or days or weeks. Breaking the cycle starts with attention. We choose to focus on something more neutral, like breathing, instead of remaining immersed inside our chaotic minds.

The practice of refocusing yourself whenever you are caught up in your inner world brings you back to your best game. When any of us gets tired, distracted, and stressed, we think less clearly and the thoughts themselves hold our attention. You needn’t focus on breathing in particular, which also isn’t magic. You can use eating, walking, the feeling of your feet on the floor, or practically any experience you choose. Your call on the garter belt.

Catching Yourself

Try this compact practice any time you find yourself rattled, overly stressed, or distracted from the person in front of you—or get started right now.

• Notice that there is a physical sensation to breathing, whatever most grabs you. It might be the rising and falling of your belly or chest, or perhaps the air moving out of your nose or mouth (or your eyelids, I suppose).

• Take 10 – 15 breaths focusing only on that physical sensation. You will almost certainly get distracted even during this short practice. That’s normal for all of us. Each time you’re distracted, return to wherever you were. When you’re done, choose what you’d like to do next.

Some Spring (Mindfulness) Training Resources

Mindful Practice from the University of Rochester

Self-compassion research and guidance from Kristin Neff

Fostering Resilience in Health Care Providers – a weekend retreat in Garrison NY this May

Meditation Instruction and resources on Mindful.org

Adapted from Psychology Today