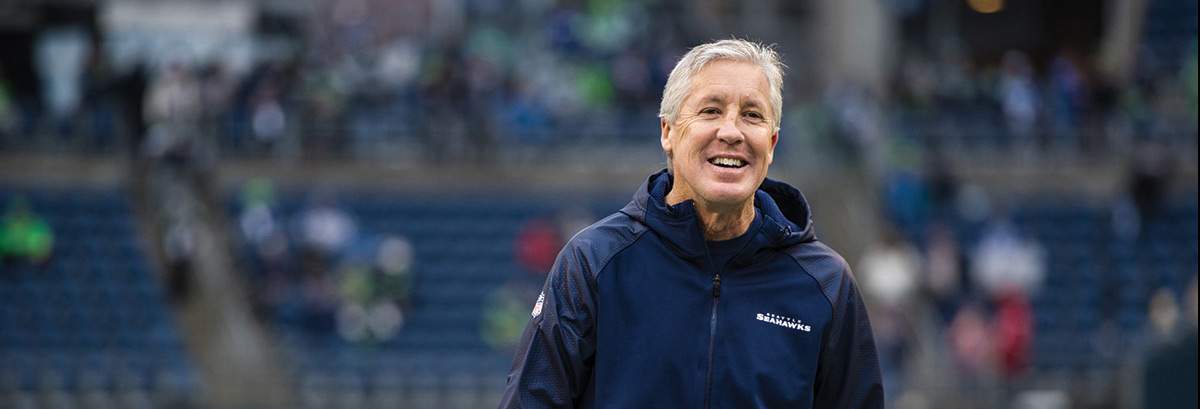

Most coaches impose standards from the outside. Pete Carroll, head coach of the Super Bowl Champion Seattle Seahawks, assisted by sports psychologist Michael Gervais, asks his players to go inside—to find the confidence to be the best they can be. He coaches the whole person, and it changes their view of the game, and of life. Hugh Delehanty reports.

The hip-hop music is blaring and Pete Carroll is loving it.

Boom dada dada da da boom.

Up on a hill overlooking the Seattle Seahawks’ practice field, an army of fans, wearing blue-and-neon-green jerseys, ski masks, and war paint are pounding drums, waving flags, and screaming love chants to their heroes. Meanwhile down on the field, quarterbacks are throwing bullets, linemen are crashing into each other, and running backs are charging up the field as if it were the Super Bowl. And Carroll, the team’s energetic 63-year-old head coach, is dancing from one corner to the next, clapping his hands, shouting props to players, and revving up the beat.

Boom dada dada da da boom.

Then just when it looks as if things couldn’t get any crazier, a task force of Marines arrives by helicopter, drops into the lake next to the field, and stages an amphibious attack on the training camp. It’s not a real attack, of course, just a show for the fans. But as the Marines swim ashore and take the beach, Carroll and the players crowd around to greet them. And in a moment of warrior solidarity, lineman Russell Okung offers to trade helmets with the sergeant in charge.

Carroll doesn’t force players to conform to a rigid, alienating system. He focuses on cultivating each player’s unique qualities, and asks them to contribute those to the team.

Most NFL coaches—especially the control-freak variety—would find this kind of hyper-charged atmosphere unbearable. But for Carroll, this is an awareness exercise. He believes in immersing his players in a world of distractions to train them to quiet their minds in the midst of chaos.

“I’m trying to create a really thriving environment,” he says. “That means making it as rich as possible. So there’s noise, competition, activity, energy—like when we play. It’s better than a pristine vacuum-type environment, as far as I’m concerned. Because we never play there. We don’t talk about mindfulness that much, but that’s how we operate. We focus on what’s right in front of us. We don’t care about the other team or the environment we’re playing in. We just take every game as if it’s the most important in the world and focus right on that. That takes great mindfulness.”

It seems to be working. When Carroll took over the Seahawks in 2010 after leading the University of Southern California (USC) Trojans to two national championships, the pundits were skeptical. Sure, they said, his positive, rah-rah approach might work with fresh-faced college boys, but not in the serious, hard-ass world of the NFL. But Carroll and general manager John Schneider slowly rebuilt the roster with players who were languishing elsewhere (e.g., star running back Marshawn Lynch), as well as out-of-the-box draft picks, such as quarterback Russell Wilson and cornerback Richard Sherman. And last season the Seahawks not only won the Super Bowl, they dominated the formidable Denver Broncos in a surehanded, seemingly effortless manner that had other NFL coaches scratching their heads and wondering what exactly Carroll was doing up there in the coffee capital of the world.

Pete Carroll has never been one to follow the crowd. While other coaches clung religiously to outdated, my-way-or-the-highway tactics, he was creating a groundbreaking approach to coaching, blending the ideas of psychologist Abraham Maslow, author Timothy Gallwey, and other thinkers with his own insights into the nature of competition and high-performance. “He’s like an independent artist,” says Yogi Roth, a TV football analyst and co-author of Carroll’s biography, Win Forever. “He’s going to sing his song the way he wants to sing it.”

“I’ve never seen a coach that players loved so much,” says veteran ESPN football writer Terry Blount. “These guys love Pete because he lets them be themselves. He gets criticized for being too freewheeling and easy, but the fact is the players are really engaged and committed.”

At the heart of his system is the revolutionary concept (in NFL circles) that the key to success is nurturing each player’s individual growth. Rather than force players to conform to a rigid, alienating system, Carroll and his coaches focus their attention on cultivating the special qualities of each player, then helping to incorporate them into the team.

“Our system is designed to allow players to be the best they possibly can be,” Carroll says. “That’s why we celebrate uniqueness, their individuality. They have to act with the team, but they can do that in a way that illuminates who they are. Most people think you can’t do that. They say there’s no space for people to be individuals within a team. I think just the opposite.”

• • •

The moment of truth for Carroll came in 2000 when he was dismissed as head coach of the New England Patriots. This was the second time he had lost a top coaching job, and he realized that, to succeed as a head coach, he needed to develop a clear philosophy of coaching that he could call his own. He came to this revelation while reading a book by legendary basketball coach John Wooden. “It took him sixteen years to figure it out,” writes Carroll in his biography, “but once he did, he absolutely knew it. After that, he rarely lost, and he went on to win ten of the next national championships. It seemed he won forever.”

Inspired, Carroll began crafting a philosophy based, in large part, on his unique view of competition. Ever since he was a boy growing up in Marin County, California, desperately wanting to be like his older brother, Jim, a three-sport star in high school, Carroll had been an obsessive competitor. Although he was so small—five-foot-four and 110 lb.—he needed a doctor’s note to play football as a high school freshman, he persisted and eventually developed into a solid all-conference player for the University of the Pacific (UOP).

“Pete has always been an underdog,” says Roth, who was an assistant coach under Carroll at USC. “He always had to prove himself, whether playing in the backyard with his brother or making the team in college. I remember my first day at USC, all he wanted to do was play one-on-one basketball. He was in his 50s and I was 20 and he wanted to play for hours. He’s the most driven person I’ve ever been around. He competes to be a great husband. He competes to be a good friend. And now he’s competing to be a great granddad.”

Carroll’s flash of insight was to make the idea of always competing the central theme of his philosophy. As he told Roth, “once you accept that you’re a competitor, you can’t turn it off.” But, in his mind, competition wasn’t about beating others, it was about pushing yourself as far as you could go. Opponents just happen to play a critical role in that process. “It’s really all about us,” he says. “We’re competing against ourselves to be our best. It’s no disrespect for our opponents. But I don’t want to place any value on our opponents from one week to the next. I want everything to be directed at us being at our best no matter who we’re playing.”

Similarly, Carroll believes it’s counter- productive to focus on results. “We don’t talk about championships,” he says. “We talk about performing at our best. And we’ve learned that that gets us what we want. As soon as we focus on something outside ourselves, it becomes a distraction and can keep us from what we have at hand.”

Carroll’s success with the Seahawks and USC has begun to shift the way many coaches think about competition. “If you look at the Latin root of ‘compete,’ it means ‘to strive together’,” notes Roth. “But if you look up ‘competition’ on your iPhone, it says ‘to strive against.’ Somewhere along the way the definition of competition shifted. Now I think Pete is bringing it back to its original meaning.”

In Carroll’s view, performance is grounded in trust and confidence, which are the source of strong focus.

At the core of his philosophy, Carroll believes that everyone—not just a few talented high draft picks—can learn how to tap into their highest potential. He was first introduced to this line of thinking when he was a grad student at UOP and starting to read Maslow, who is best known for his research on “hierarchy of needs” and “self-actualization.” In his studies of high achievers, Maslow discovered that many of his subjects frequently had what he called “peak experiences,” moments of intense clarity that gave them access to parts of themselves that were usually hidden.

After reading this, Carroll imagined creating situations for players to develop the confidence to set their talents free and pursue their potential, rather than forcing them to perform a certain way. However, one of his early experiments along these lines when he was an assistant coach at UOP was disappointing. He asked the defensive backs what they needed to improve and incorporated their ideas into the next day’s practice. But when the head coach found out, he scowled, “Don’t you ever ask the players what they want.”

Still, Carroll kept experimenting with ways to train players to unlock their hidden powers. “The possibility to reach your highest level is available to everyone if you work hard and go about it the right way,” he says. “I think there are so many things that can distract us from getting to that clarity. But we all have the power to figure that out if guided properly and coached well enough. Everybody needs to be coached. I know I do.”

When I ask him who he considers his coach, he laughs and says his wife, Glena.

During his grad school years, Carroll was also intrigued by the work of Gallwey, the author of The Inner Game of Tennis, who concluded that the biggest obstacles most athletes face are the doubts, fears, and lapses in focus that arise in high-pressure situations. The solution, he prescribed, was to quiet the mind by shifting attention to what was actually happening in any given moment. As Gallwey put it, “The greatest efforts in sports are when the mind is as still as a glass lake.”

Gallwey focused primarily on individual sports, such as golf and tennis, but Carroll was convinced his insights could have a dramatic impact on teams as well. “The foundation of performance is trust and confidence, which allows you to focus,” he says. “That’s what I learned from Gallwey. I’ve taken some of what he says and directed it toward the team, as if they are one mind, one person. I try to develop the confidence of the whole team so that they can perform without fear and play the way they’re capable of.”

Several years ago, Michael Murphy, the cofounder of the Esalen Institute, introduced Carroll to an American Indian concept known as “long body.” It was discovered by researcher W.G. Roll while studying Iroquois tribes. He found that under certain conditions individuals within the group developed a “single consciousness.” The tribe, Roll wrote, “is likened to a body connected where, once connected, it operates as a single entity, functioning, sensing, and feeling as one.”

“That made sense to me,” says Carroll, “because that’s exactly the process we go through as a team. That connectedness is available to us at all times. But you have to invest in it to make it come to life. You earn that connection with all the sharing you do and all the common experiences you have. It takes big things to happen to draw you together so that you can operate in a more connected fashion.”

• • •

When Carroll arrived in Seattle, his dream was to build a support staff dedicated to improving the team’s physical and psychological readiness in a way that no other NFL team had done. He even created a department focused on monitoring the players’ sleep, nutrition, fatigue, and energy levels, and helping them master the nuances of personal excellence. As Sam Ramsden, the director of player health and performance, puts it, “The players are performing for the team and we’re performing for them.”

A key figure in that effort is Michael Gervais, a sports psychologist with a strong background in mindfulness who has trained numerous pro athletes and Olympians,

including three-time gold-medal-winning beach volleyballers Kerri Walsh-Jennings and Misty May-Treanor. When he met Carroll in 2011 he was struck by how “switched on” the Seahawks culture was compared to other teams he had worked with. “In some cultures, the coaching environment challenges athletes but doesn’t necessarily build the entire human,” he recalls. “Pete is the only coach I know who has created a shared language between the coaches and the players that’s completely grounded in the science of psychology.”

Gervais uses tactical breathing, visualization, and mental-imaging techniques to cultivate “full presence and conviction in the moment.”

Gervais teaches players meditation, which he calls tactical breathing, as well as a broad range of visualization and mental-imaging techniques. He also helps them balance the physical, mental, and spiritual aspects of sports and make mindfulness an integral part of their daily lives. While other sports psychologists focus on training players pre-performance rituals, Gervais uses a sophisticated blend of mindfulness and cognitive behavioral training to cultivate what he describes as “full presence and conviction in the moment.”

One thing he devotes a lot of attention to is getting athletes to understand the mechanics of confidence. “Confidence is the cornerstone of great performance,” he explains. “And it comes from just one place: what we say to ourselves.” To be effective, it must be “grounded in credible conversations with yourself,” he adds. “Which means you have to have a disciplined mind to focus on when you’ve been successful in the past and to bring that success into the present. Part of the training is being mindful, on a moment-to-moment basis, of whether you’re building or taking away from your confidence. The second part is being able to guide yourself back to the present moment and adopt a positive mindset about what is possible.”

A good example is Doug Baldwin, a gifted wide receiver who struggled early in his career with inconsistent performance. When he started with the Seahawks, he had a lot of negative thoughts that were hampering his ability to focus. So Gervais taught him to create mental highlight reels based on moments from the past when he had performed extremely well. The effect was startling. “Every time I slip back into doubtfulness,” Baldwin says, “I go back to those highlight reels and it puts me in a positive mind. I think, ‘This is what’s going to happen.’ And eventually it does.”

Free safety Earl Thomas takes a somewhat different tack. Working with Gervais, he adopted a keen interest in mindfulness practice, and it has changed his way of looking at the world. “It’s an inner thing,” he says. “When you’re quiet and don’t say anything, you start to see the unseen. That’s why people need to be observant and listen. When I turned my ears to listening, I improved, personally and in everything.”

Asked whether he meditates, Thomas replies,

“You’ve got to. That’s how you get into the flow. That’s why I do my little dance, my back pedal, because I’m flowing with the offense. However, you’re going to get at me, I’m going to adapt. I’m going to flow with you like water.”

“Seeing the unseen” is how Gervais describes the ability to recognize the truth of what is. “The truth is often something that you can’t see, but it’s something you can experience and feel,” he says. “To get the players to experience that, we work on being present, grounded, and connected—and sometimes training our minds to envision what we’d like to experience. That’s the essence of the moment.”

This kind of intimate coaching is not uncommon with the Seahawks. “We’re a relationship-based system,” says Carroll. “It’s based on our ability to interact with our players, to understand their needs, and, through those relationships, figure out how best to help them. That’s why we get such a great return from our guys because, after a while, they know how consistent we are and that we’re going to be there for them.”

Offensive line coach Tom Cable, whose last gig was as head coach of the Oakland Raiders, was pleasantly surprised when he started using Carroll’s approach. “There’s a level of development that’s always around us, developing the players, developing the program, developing everything that can make the team better,” he says. “And there’s a real vibe of what it means to be positive and make each day the most important thing there is. And not worry about yesterday or look to tomorrow. Just stay right here right now. When you grab onto that philosophy, you get so much done.”

It also makes it easier to deal with emotionally sensitive issues. Carroll’s strategy for handling difficult discussions, he says, is “getting to the truth always. In a calm measured way so that we can talk things through. The depth we can get to is based on the trust that we’ve developed.”

Case in point: the Ray Rice situation. Carroll was shaken by the news that the Baltimore Ravens running back had been caught on video beating his then fiancee in an elevator and told ESPN’s Terry Blount that the incident had “changed him forever” and would impact how he evaluated players in the future. “I talked to the team about the serious nature of it,” he told Blount. “It’s an extremely serious situation. We made them aware that we will help them in any way if they have concerns about it. We will try to elevate their awareness. I think it’s another example of an enormous situation that people learn from and grow so much from.”

• • •

One morning in 2003 Carroll was driving to work at USC and heard on the radio of a gang-related murder of a young man, the 11th of its kind that week in Los Angeles. Carroll was disturbed by the news because many of the kids being killed were similar in age to the players on the Trojans team. So he reached out to his friend Lou Tice, the head of The Pacific Institute, an educational foundation, to figure out a way to address the problem.

Soon afterward, Carroll and Tice convened a meeting of several leaders who were grappling with gang violence, including Mayor Villaraigosa, and were surprised to discover that they didn’t have a clearly articulated philosophy. So he described what he was doing at USC, thinking that the basic principle—building success by getting each team member to maximize his or her potential—could work with all kinds of organizations, not just football teams.

What emerged was a non-profit organization called A Better L.A. that works with a wide range of community groups to restore peace, save lives, and give young people in gang-scarred areas the resources for self-empowerment. The results have been impressive. According to the Los Angeles Times, a number of key gang-crime statistics have declined significantly since A Better LA was founded. Three years ago, Carroll launched a similar program in his new city, fittingly dubbed A Better Seattle.

Carroll is reluctant to talk about his involvement in these programs. For him, it’s not about garnering attention, but connecting one-on-one with troubled young men and trying to help them re-envision their lives.

When Dave Boling, a sports columnist for Tacoma’s The News Tribune, first encountered Carroll he thought he was a typical “pep-talk” coach, all glib and shiny without much substance. But he changed his opinion when he interviewed two veteran L.A. cops who’d worked with Carroll and called him their “hero.” These were “hard-edge, no B.S.” guys who had each lost partners to gang violence. They said that Carroll’s ability to bring attention to the problem was important, wrote Boling, “but the bigger thing is that he’s for real, and goes out in the middle of the night for heart-to-heart talks with these kids and their families.”

Yogi Roth recalls going out one night with Carroll to visit a crime-torn neighborhood in L.A. and ending up standing under a street lamp together at 2 a.m.

“Why do you do this, man?” Roth asked Pete.

“I kind of have to.”

“But it’s your birthday today,”

“What else am I going to do?” replied Carroll, laughing. “This is what I have to do.”

To Roth, this was a sign of Carroll’s intuitive sense of compassion.

Compassion isn’t a word bandied about that often in NFL locker rooms. But it’s one of the qualities that the Seattle players admire most about Carroll. As wide receiver Doug Baldwin puts it, “I was raised to believe that a leader should serve others. And Coach Carroll is like that. Everything he does is to serve others.” •