You’ve probably found yourself, on occasion, spending long uninterrupted hours with digital technologies, particularly during months of social distancing. Just as our smartphones are always close at hand (both to serve and to distract), the feelings engendered by digital tech have become our frequent if not constant companions. There is an almost palpable pain when boredom approaches, as it does if you are briefly alone with your thoughts—a sensation all the stranger, now, for our ease of escaping it. There is a loneliness that creeps in when you wonder if virtual friends and digital conversations are really the equals of those IRL. There is a narcissism that yearns to cry out to the world, via tweet or Instagram post, I’m over here! Observe the wonder that is me. And there is the anxiety about being out of the loop, felt by so many, so often, that it merits its own acronym: FOMO.

Of all the consequences of digital technologies, few are as profound as those related to our emotional lives. That is not to minimize their effects on the cognitive part of our brain, including the ability to remember and focus, as I wrote about in a 2017 column. Call me biased, but my feelings feel more like me than do my powers of attention and recall. So when historian Susan J. Matt and technology scholar Luke Fernandez of Weber State University in Utah (a married couple) told me that “a new American emotional style…is taking shape today” as a result of digital technologies that have “radically remade” our feelings and sense of self, it resonated.

At first, I thought theirs was a now-commonplace observation about how the internet stokes anger (have you managed to resist an irate retort to a political tweet?), narcissism (of course the world is interested in a photo montage of your breakfast), and loneliness (why don’t I have more Facebook “friends”?). But for Matt and Fernandez, those observations are only a starting point. Their analysis, as laid out in their 2019 book Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid: Changing Feelings about Technology, from the Telegraph to Twitter, is—to use an overused but, in this case, apt term—meta.

How Do You Feel About Your Feelings?

People have always experienced boredom and loneliness and a need for recognition, as Matt and Fernandez discuss through fascinating historical citations. For make no mistake, earlier generations, too, felt the emotional consequences of tectonic technological shifts. When people “fell in love with” photography and factory-made mirrors in the 19th century, pundits also worried about rampant narcissism. And if you think Reddit is the first form of communication to encourage anger, let Matt and Fernandez introduce you to the “Indignation Meetings” of 150 years ago, where attendees decried everything from the acquittal of an accused murderer to monopolies.

What has changed is how we process and interpret those feelings. That is, the immediate feel of the feelings is the same as it has been for as long as emotions have been part of our neuro-repertoire. But how we process them cognitively is different than it was for generations that preceded us. What has changed is how we feel about those feelings (that’s the “meta” part). As they scoured history for clues to people’s emotional lives, Matt said, “what became clear was that boredom and loneliness and narcissism were changing today.” In particular, Fernandez chimed in, “the language we use to describe our feelings has changed. We used to be resigned to boredom and loneliness, for example, but now we pathologize them; we think of them as afflictions that need to be cured.”

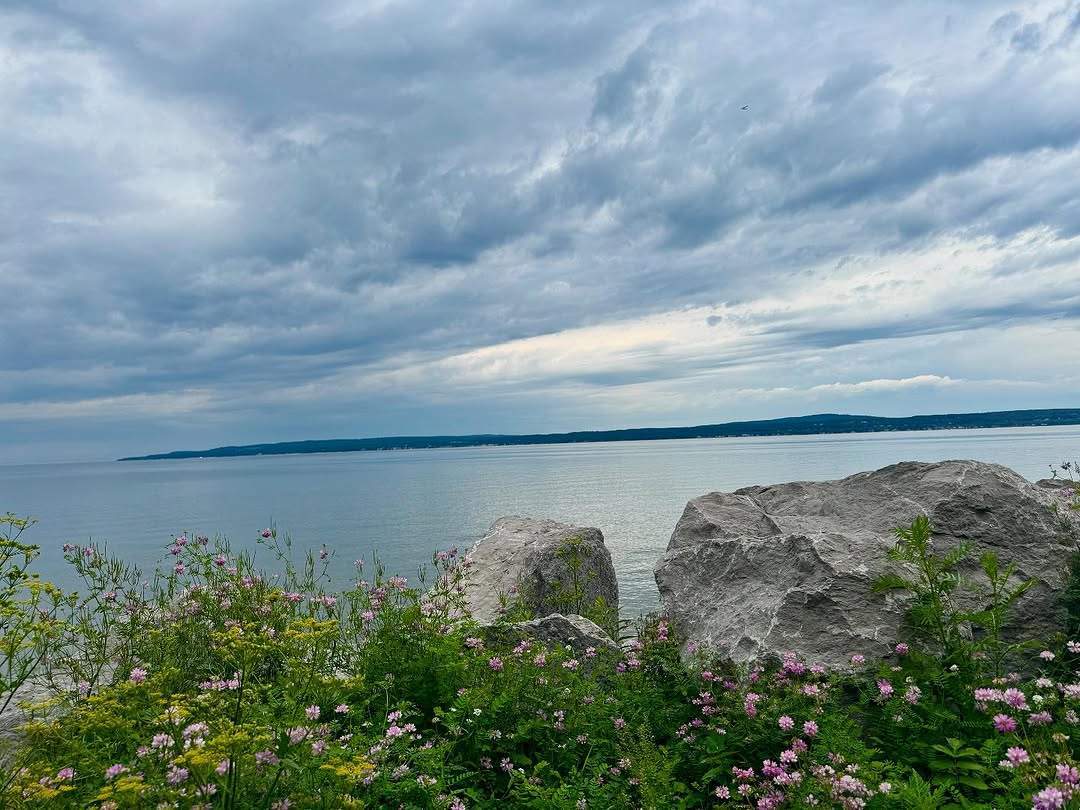

Loneliness, for instance, was once seen as part of the human condition; some 19th-century Americans chopped down telegraph poles in a futile attempt to maintain solitude. But today “being disconnected makes an increasing number of Americans uncomfortable and anxious,” as the social distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic made all too clear. Solitude is widely seen as synonymous with loneliness, which has been turned “into a formal malady with purchasable cures,” Matt and Fernandez write.

“The language we use to describe our feelings has changed. We used to be resigned to boredom and loneliness, for example, but now we pathologize them; we think of them as afflictions that need to be cured.”

Although they do not use the word in their examination of how feelings about feelings have changed, they are describing a form of mindfulness. And what gave me hope that we are not doomed to experience the negative feelings about the negative feelings provoked by digital technologies is something Matt and Fernandez experienced as a result of their research. Through that process of immersing themselves in the history, sociology, and psychology of meta-feeling, they found ways to “better navigate our feelings and make more informed choices about when to be narcissistic, lonely, bored, inattentive, awed, and angry.” Emotions, they add, “are not natural, inevitable, or fixed; they change and are changeable.”

That assertion comes from the fascinating theory of “constructed emotions” pioneered by psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett of Northeastern University. “How you interpret emotions depends on the cultural context,” Matt said. “Different emotions have a different meaning and feeling due to cognitive processing.” If the cognitive part of the brain imposes on the raw feeling of boredom or loneliness the interpretation, “something is wrong here, do all you can to escape this negative emotional state,” then the feeling of boredom or loneliness becomes doubly painful. “Feelings do arise organically,” Fernandez said. “But we then impose cognitive interpretations on them.”

Choosing to Flip Your Emotional Script

Consider the cognitive interpretation of boredom. The word did not even exist until the mid-1800s. When people received no cognitive stimulation from the outside world, which is how we understand boredom today, they did not take it as a sign that they needed to frantically find external stimulation to awaken their synapses. They filled it with an interior life. “We search so ceaselessly for constant diversion, our ability to sit still has gone,” Matt said. “There is an almost frenetic search for stimulation.” Many of us would rather be subjected to an electrical shock than “do nothing” for 15 minutes, as was true of two-thirds of men and one-quarter of women in a 2014 study.

But this raw feeling that our thinking mind has been taught to label as boredom “need not be an affliction,” she continued. (By “raw feeling,” I mean the immediate, felt emotion, before the cognitive mind imposes an interpretation on it.) “It can be a time for random thoughts to pass through your brain,” and a time for creativity, Matt said. This invitation to transform the way we feel about boredom—actually, scratch that: let’s start calling it an absence of external mental stimuli that can in fact be a glorious gift—is one that’s been visited time and again in Mindful’s pages, by teachers including Barry Boyce and Manoush Zomorodi. With effort and perspective, and aided by mindfulness practice, we can perform a cognitive jujitsu on the raw feeling of boredom and turn it into a gift of mental quietude to be filled with a richer interior life.

The same goes for emotions as seemingly disparate as narcissism and loneliness. Narcissistic self-promotion runs rampant on social media platforms, encouraging us to regard every thought and experience—I was here! This is what I think!—as worthy of sharing with the world. (While Twitter, Instagram, and selfie sticks have many constructive uses, their ubiquity also points to narcissist culture.) Even as the pandemic has infected millions across the globe, we’ve created fake backgrounds for our Zoom images.

Digital technologies made users “relabel” and “reinterpret” the feeling of being alone.

But the background to this typically self-centered behavior is, to a great extent, not knowing how to be alone with ourselves anymore. Matt observes that our anxious longing for connection spurs us to become curators and promoters of our image, hoping to accumulate likes, followers, and “friends.” As the evolution of digital technologies has helped us “connect” more and more, our emotional tolerance for being alone has plunged. According to the Google Ngram Viewer, which counts the frequency of words and phrases in books, the use of “solitude” has plunged since the late 1920s (when radio and then television entered homes) while the frequency of “loneliness” has risen.

Digital technologies made users “relabel” and “reinterpret” the feeling of being alone, Matt and Fernandez argue, and in so doing changed the actual feelings that go with aloneness. But that’s not irreversible. Rather than interpreting the sense of aloneness as one that demands redress—let me just check my Facebook feed, it’ll take just a sec—we can accept it as part of life, even as an opportunity. “Humans can collectively shape these feelings that digital technologies give us,” Matt said. “We do have some agency.”

read more

How Much Self-Knowledge is Too Much?

Sharon Begley explores the science of self-insight and the research on how much you should know about yourself before it becomes detrimental to your health. Read More

Making Friends with Difficult Emotions

Cultivating a clear awareness of our inner world during moments of strong emotion is a powerful, portable way to step back from the activation, find our calm, and discover a right way forward. Read More

Three Mind Tricks That Keep You Addicted to Your Phone

Social media channels, app companies—they don’t want you to stop scrolling, so they’ve enlisted the top mind hacks from psychology to keep you craving for more. Here are three ways your mind is being tapped to linger longer and five tips for getting unhooked. Read More