Adolescence is as much a perplexing time of life as it is an amazing one. Running roughly between the ages of twelve and twenty- four (yes, into our mid-twenties!), adolescence is known across cultures as a time of great challenge for both adolescents and the adults who support them. Because it can be so challenging for everyone involved, I hope to offer support to both sides of the generational divide. If you are an adolescent, my hope is that the information I am offering will help you make your way through the at times painful, at other times thrilling personal journey that is adolescence. If you are the parent of an adolescent, or a teacher, a counselor, an athletic coach, or a mentor who works with adolescents, my hope is that these explorations will help you help the adolescent in your life not just survive but thrive through this incredibly formative time.

In recent years, surprising discoveries from brain imaging studies have revealed changes in the structure and function of the brain during adolescence. Interpretations of these studies lead to a very different story than the old raging-hormone view of the teenage brain. A commonly stated but not quite accurate view often presented by the media is that the brain’s master control center, the prefrontal cortex, at the forward part of the frontal lobe, is simply not mature until the end of adolescence. This “immaturity” of the brain’s prefrontal cortex “explains immature teenage behavior.” This simple story, while easy to grasp, is not quite consistent with the research findings and misses an essential issue.

Instead of viewing the adolescent stage of brain development as merely a process of maturation, of leaving behind outmoded or non useful ways of thinking and transitioning to adult maturity, it is actually more accurate and more useful to see it as a vital and necessary part of our individual and our collective lives. Adolescence is not a stage to simply get over; it is a stage of life to cultivate well. This new and important take-home message, inspired by the emerging sciences, suggests that the changes that occur in the adolescent brain are not merely about “maturity” versus “immaturity,” but rather are vitally important developmental changes that enable certain new abilities to emerge. These new abilities are crucial for both the individual and our species.

Why should this matter to us, whether we are teens, in our twenties, or older? It matters because if we see the adolescent period as just a time to wade through, a time to endure, we’ll miss out on taking very important steps to optimize the essence of adolescence.

Yes, there are challenges in staying open to the “work” of adolescence. Important opportunities for expansion and development during this time can be associated with stress for teens and for the parents who love them. For example, the pushing away from family that adolescents tend to do can be seen as a necessary process enabling them to leave home. This courage to move out and away is created by the brain’s reward circuits becoming increasingly active and inspiring teens to seek novelty even in the face of the unfamiliar as they move out into the world. After all, the familiar can be safe and predictable, while the unfamiliar can be unpredictable and filled with potential danger. One historical view for us as social mammals is that if older adolescents did not leave home and move away from local family members, our species would have too much chance of inbreeding and our genetics would suffer. And for our broader human story, adolescents’ moving out and exploring the larger world allows our human family to be far more adaptive in the world as the generations unfold. Our individual and our collective lives depend on this adolescent push away.

What we are coming to see is that there is a crucial set of brain changes during our adolescence creating new powers, new possibilities, and new purposes fueling the adolescent mind and relationships that simply did not exist like this in childhood. These positive potentials are often hidden from view and yet they can be uncovered and used more effectively and more wisely when we know how to find them and how to cultivate them. We can learn to use cutting edge science to make the most of the adolescent period of life. It’s a pay-it-forward investment for everyone involved.

For the teen, the growth of the body itself, with alterations in physiology, hormones, sexual organs, and the architectural changes in the brain, also can contribute to our understanding of adolescence as an important period of transformation. Changing emotions revolutionize how we feel as teens inside, making more complex the ways of processing information and our ideas about the self and others, and even creating huge developmental shifts and transitions in the inner sense of who we are and who we can become. This is how a sense of identity shifts and evolves throughout adolescence.

From the inside, these changes can become overwhelming, and we may even lose our way, and feel that life is just “too much” to navigate at times. From the outside, such changes may at times seem like we are lost and “out of control.” Our adolescent years can be challenging for sure. But the great news is that with increased self-awareness of our emotional and social lives, and with an increased understanding of the brain’s structure and function, the powerful positive effects of the complex changes that occur during adolescence can be harnessed with the proper approach and understanding.

Myths About the Teenage Brain

There are a few myths surrounding adolescence that science now clearly shows us are simply not true. And even worse than being wrong, these false beliefs can actually make life more difficult for adolescents and adults alike. So let’s bust these myths right now.

1. Raging Hormones Make You Crazy

One of the most powerful myths surrounding adolescence is that raging hormones cause teenagers to “go mad” or “lose their minds.” That’s simply false. Hormones do increase during this period, but it is not the hormones that determine what goes on in adolescence. We now know that what adolescents experience is primarily the result of changes in the development of the brain. Knowing about these changes can help life flow more smoothly for you as an adolescent or for you as an adult with adolescents in your world.

2. You Just Need to Grow Up

Another myth is that adolescence is simply a time of immaturity and teens just need to “grow up.” With such a restricted view of the situation, it’s no surprise that adolescence is seen as something that everyone just needs to endure, to somehow survive and leave behind with as few battle scars as possible. Yes, being an adolescent can be confusing and terrifying as so many things are new and often intense. And for adults, what adolescents do may seem confounding and even senseless. Believe me, as the father of two adolescents, I know. The view that adolescence is something we all just need to endure is very limiting. To the contrary, adolescents don’t just need to survive adolescence; they can thrive because of this important period of their lives. What do I mean by this? A central idea that we’ll discuss is that, in very key ways, the “work” of adolescence—the testing of boundaries, the passion to explore what is unknown and exciting—can lay the stage for the development of core character traits that will enable adolescents to go on to lead great lives of adventure and purpose.

3. Strive for Total Independence

A third myth is that growing up during adolescence requires moving from dependence on adults to total independence from them. While there is a natural and necessary push toward independence from the adults who raised us, adolescents still benefit from relationships with adults. The healthy move to adulthood is toward interdependence, not complete “do-it-yourself” isolation. The nature of the bonds that adolescents have with their parents as attachment figures changes, and friends become more important during this period. Ultimately, we learn to move from needing others’ care during childhood, to pushing away from our parents and other adults and learning to lean more on our peers during adolescence, to then learning to both give care and receive help from others. That’s interdependence.

When we get beyond the myths, we are able to see the real truths they mask, and life for adolescents, and the adults in their lives, gets a whole lot better.

Unfortunately, what others believe about us can shape how we see ourselves and how we behave. This is especially true when it comes to teens and how they “receive” commonly held negative attitudes that many adults project (whether directly or indirectly)—that teens are “out of control,” or “lazy” or “unfocused.” Studies show that when teachers were told that certain students had “limited intelligence,” these students performed worse than other students whose teachers were not similarly informed. But when teachers were informed that these same students had exceptional abilities, the students showed marked improvement in their test scores. Adolescents who are absorbing negative messages about who they are and what is expected of them may sink to that level instead of realizing their true potential. Adolescence is not a period of being “crazy” or “immature.” It is an essential time of emotional intensity, social engagement, and creativity. This is the essence of how we “ought” to be, of what we are capable of, and of what we need as individuals and as a human family.

The Benefits and Challenges of Adolescence

The essential features of adolescence emerge because of healthy, natural changes in the brain. Since the brain influences both our minds and our relationships, knowing about the brain can help us with our inner experience and our social connections to others. During the teen years, our minds change in the way we remember, think, reason, focus attention, make decisions, and relate to others. From around age twelve to twenty-four, there is a burst of growth and maturation taking place as never before in our lives. Understanding the nature of these changes can help us create a more positive and productive life journey.

Life is on fire when we hit our teens. While the adolescent years may be challenging, the changes in the brain that help support the unique emergence of the adolescent mind can create qualities in us that help not only during our adolescent years, if used wisely, but also as we enter adulthood and live fully as an adult. How we navigate the adolescent years has a direct impact on how we’ll live the rest of our lives. Those creative qualities also can help our larger world, offering new insights and innovations that naturally emerge from the push back against the status quo and the energy of the teen years.

For every new way of thinking and feeling and behaving with its positive potential, there is also a possible downside. Yet there is a way to learn how to make the most of the important positive qualities of the teenage mind during adolescence and to use those qualities well in the adult years that come later.

Brain changes during the early teen years set up four qualities of our minds during adolescence: novelty seeking, social engagement, increased emotional intensity, and creative exploration. There are changes in the fundamental circuits of the brain that make the adolescent period different from childhood. Each of these changes is necessary to create the important shifts that happen in our thinking, feeling, interacting, and decision-making during adolescence.

NOVELTY SEEKING emerges from an increased drive for rewards in the circuits of the adolescent brain that creates the inner motivation to try something new and feel life more fully, creating more engagement in life.

Downside: Sensation seeking and risk taking that overemphasize the thrill and downplay the risk resulting in dangerous behaviors and injury. Impulsivity can make an idea turn into an action with a pause to reflect on the consequences.

Upside: Being open to change and living passionately develop into a fascination for life and a drive to design new ways of doing things and living with a sense of adventure.

SOCIAL ENGAGEMENT enhances peer connectedness and creates new friendships.

Downside: Teens isolated from adults and surrounded only by other teens have increased-risk behavior, and the total rejection of adults and adult knowledge and reasoning increases those risks.

Upside: The drive for social connection leads to the creation of supportive relationships that are the research-proven best predictors of well-being, longevity, and happiness throughout the life span.

INCREASED EMOTIONAL INTENSITY gives an enhanced vitality to life.

Downside: Intense emotion may rule the day, leading to impulsivity, moodiness, and extreme sometimes unhelpful reactivity.

Upside: Life lived with emotional intensity can be filled with energy and a sense of vital drive that give an exuberance and zest for being alive on the planet.

CREATIVE EXPLORATION with an expanded sense of consciousness. An adolescent’s new conceptual thinking and abstract reasoning allow questioning of the status quo, approaching problems with “out of the box” strategies, the creation of new ideas, and the emergence of innovation.

Downside: Searching for the meaning of life during the teen years can lead to a crisis of identity, vulnerability to peer pressure, and a lack of direction and purpose.

Upside: If the mind can hold on to thinking and imagining and perceiving the world in new ways within consciousness, of creatively exploring the spectrum of experiences that are possible, the sense of being in a rut that can sometimes pervade adult life can be minimized and instead an experience of the “ordinary being extraordinary” can be cultivated. Not a bad strategy for living a full life!

Excerpted from Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain by Dr. Daniel Siegel. Copyright © 2013 by Daniel Siegel. Excerpted by permission of Tarcher/ Penguin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Profiles of 2 Young Minds

Two teenagers—who have all practiced mindfulness through iBme*—talk about how meditation has helped them.

Nathan Worthen, 19

The teen years can be a frightening, dark time. I’ve had friends go every which way—depressed, wild, in trouble. I’ve had some of that too. When you pass the puberty line, the change is so overwhelming it hits like a truck. Hormones bring on emotions that attack from every direction, and you also have so much more intellectual capacity than you did when you were child. You have so many more thoughts and feelings about what’s going on around you. It sometimes makes you want to hide from the world or indulge yourself.

When adults lead with words but not by example, it’s less effective. You see them as authority figures instructing instead of living their own lives. The great thing about the mindfulness teachers I’ve had during my retreats is that they’re always learning, developing their minds. I’m inspired to follow that example. My biggest challenge is to be more generous to myself. The retreats have helped me stop thinking of myself as an idiot if I slip up. Being a teenager is trial and error time. There are a lot of mistakes to be made, but when you learn to rebound from them, it makes you stronger.

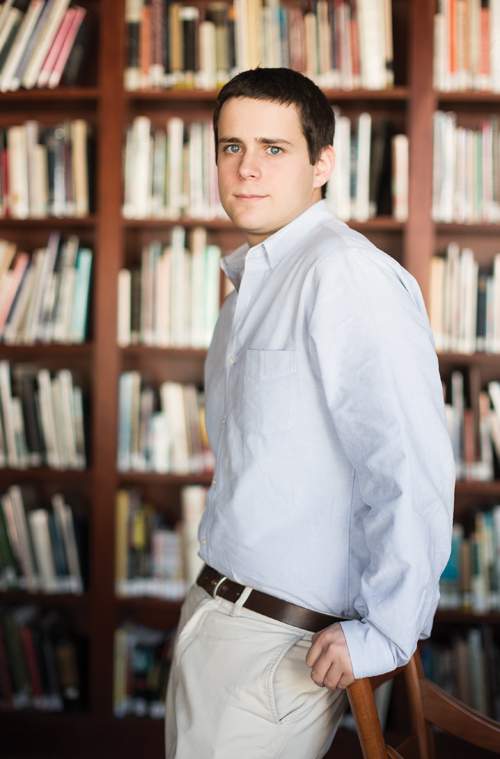

Ben Painter, 18

I’m president of the student body at Middlesex School, Concord, Massachusetts. We incorporate a mindfulness class into the curriculum—every freshman takes it and can keep doing it later on.

The biggest challenge in my life is managing time. There’s a lot of pressure: the tough college application process; having as many extracurricular activities as possible; art or community service or whatever. I play tennis and I do giant slalom skiing. Balancing all these things with homework, it’s definitely a struggle.

I didn’t come to mindfulness because of emotional struggle, but more because it helps me with my aspirations and ambitions. I’m a self-motivated guy, so I have pressure coming from within. If I’m tense or nervous before a game or test, I do a short mindfulness practice or a body scan. It’s nice to listen to my body more, instead of only thinking of the tasks I have coming up. Taking a little time to be in the moment has helped me deal better with pressure—it relaxes me. I feel like I do a lot better on tests too. It’s taught me to be more present with friends when hanging out. Not always on my phone.

Through mindfulness I’ve learned that it’s not about achieving everything, it’s about having a good attitude, taking it in stride, and doing better the next time around.

Interview with Dr. Dan Siegel: Why I Wanted to Write Brainstorm

The experience of raising his own children and grappling with the fascinating changes adolescence brings inspired the psychiatrist to investigate the radical changes happening in young brains. He wishes he knew what he knows now when his children were teenagers.

Mindful: Why do you think Brainstorm has become so popular?

Dan Siegel: I’m guessing because it’s refreshing news. We’ve been dealing with this period of life in very negative ways, and it’s time to shift the conversation and make use of some helpful scientific understanding.

MF: What motivated you to write the book?

DS: When my children left their teenage years, I wanted to try to understand all the experiences we’d had as a family. I started looking at the popular literature and found a lot of material was insulting to adolescents. There was nothing to help parents or adolescents learn about the new discoveries in the science of the adolescent brain.

MF: If you knew what you know now, would you have done anything differently?

DS: I sure learned a lot researching this book. As a result, I imagine I would have been more patient with my own adolescents, more spacious in my own mind, so that when they pushed against me, I wouldn’t have taken it as personally. When you understand that nature has created changes in the adolescent brain that prepare the child to move from soaking in the knowledge of the world from adults to pushing them back, you have more understanding and appreciation. You see just how much they’re remodeling their brains to see the world through new eyes.

MF: What can an adolescent learn from this book?

DS: An adolescent can learn about what’s going on in their brains in ways they haven’t been taught before. It can debunk the destructive and disempowering myths they’re subject to. Knowing that their brain is going through necessary and positive changes can empower them to face the struggles that come with the quest to find their identity, their place in the world, with more selfunderstanding. In seeing the drive of the brain to explore new things, for example, they may see both the benefit and the risk. As a result, they may find their way toward choices that lessen the risk. If you want the thrill of going fast, for example, you probably don’t want to do it in cars on highways while drinking.

MF: Yet parents are so often the boundary setters.

DS: Quite right. That’s the big challenge. When you say, “Under no circumstance do I want you to do X” to an adolescent, X becomes the very thing they want to do. If an adult—a parent, a teacher, a coach—can embrace their adolescent’s biological need to push back, they can frame things differently. Adults too often assume adolescents are stupid, that they don’t have the capability to develop and follow an inner compass, that they have to be protected from themselves.

MF: How do you do things differently, then?

DS: First off, treat them as people who have the capability to develop an inner compass. It’s just that their brain deemphasizes the downside of risks. By exploring risk with them, you can help foster the development of the compass they will follow in making decisions throughout their life—far preferable to trying to make the decisions for them. That short-circuits the process of moving from dependence to interdependence.

You can also encourage practices that cultivate what I call “mindsight,” the ability to see or know the mind, and I suggest a number in Brainstorm. It’s possible to cultivate a spaciousness of mind that allows us to take in whatever is arising from others and inside ourselves with more openness and presence. And that can help us all navigate this period well—and revive some of the spirit of adolescent exploration when we find it lacking later in life.