Over the past decade social scientists have taken a deep dive into what seems like a straightforward question: What makes us happy? The pursuit of pleasure? The absence of hardship and difficulty? Or, seen from a longer view, the feeling that your life has meant something?

The answer has proven less obvious, and largely depends on whom you talk to. When it comes to the science of happiness, researchers still don’t fully agree on how to measure it or, even, a clear definition of what “happiness” is.

Take, for example, the widely reported and controversial “happiness gap” finding that parents are less happy than people who don’t have children. One of many studies, a survey of 397 adults, found that parenting may provide meaning in life but not necessarily happiness.

But when researchers from the University of California, Riverside, measured both happiness and meaning together, parents, in general, came out happier and more satisfied in their lives than people without children. “When you feel happy, and you take out the meaning part of happiness, it’s not really happiness,” researcher Sonja Lyubomirsky told Greater Good Science Center.

Differences like this have spurred a new inquiry into what actually qualifies as happiness.

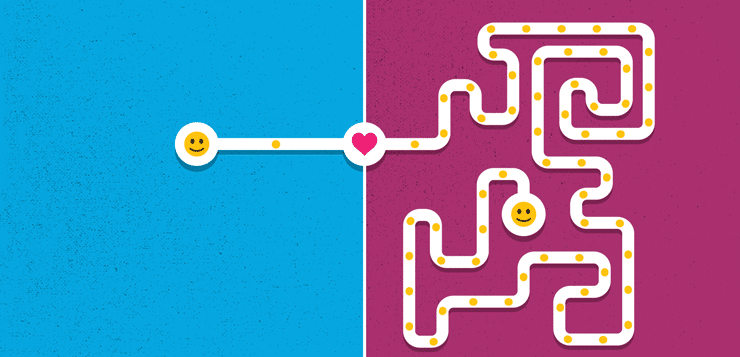

And it’s generated new interest in a 2,500-year-old theory that there are two types of happiness: hedonic (positive feelings associated with pleasure or goal fulfillment) and eudaimonic (positive feelings derived from pursuing meaning).

Hedonic is about in-the-moment pleasure. It’s the pursuit of enjoyment—fun for fun’s sake. It’s focused on your own wants and needs and has an energetic, upbeat quality.

Eudaimonic (pronounced u-duh-MOH-nic ) is more about fulfilling your higher potential instead of an immediate desire. It’s associated with things like seeing the big picture, aligning yourself with a larger purpose, and helping others.

“Positive emotions can help you connect more with others, broaden your attention, make your thinking more flexible, and increase your ability to see the big picture.”

While both can evoke good feelings, current measurements of straight-up happiness—things like greater positive affect and less negative affect—typically fall in the hedonia camp. Eudaimonic pursuits, on the other hand, may not bring a lot of pleasure. In fact, activities and life focus that provide a sense of meaning often involve times of struggle and stress.

So… how does this make you happy? Some scientists argue that the pursuit of meaning, self-growth, and alignment with something outside of yourself, while not always fun, leads to greater life satisfaction overall than the pursuit of pleasure alone.

It may be better for your health, too. Studies have revealed a slew of health benefits from eudaimonic pursuits, such as volunteering. A 2013 study found that people who derived their happiness by having a sense of meaning had a stronger immune profile; literally, their brand of happiness reaches down to their cells. They also are less reactive to stress, have higher HDL (“good”) cholesterol levels, sleep better, and may experience less depression. Meanwhile, people who identify more with hedonic happiness show greater pro-inflammatory gene expression, the kind common among people exposed to chronic stress or trauma.

For all of these reasons, it might be easy to surmise that eudaimonia is the one true path to happiness. Yet some scientists warn against this kind of one-is-better thinking.

Elizabeth Dunn at the University of British Columbia tells the Greater Good Science Center, “To say that there’s one pathway to meaning, and that it’s different than the pathway to pleasure, is false.”

Fun, laughter, and enjoyment are all essential elements of the life experience. And these effects are not experienced in a vacuum. In fact, Dunn and others point out, feeling positive emotions can help you connect more with others, broaden your attention, make your thinking more flexible, and increase your ability to see the big picture, all of which may contribute to seeing and aiming for greater meaning.

Researcher Veronika Huta writes that each plays an important role in the cultivation of a good life. People who pursue a balance of both hedonic and eudaimonic happiness have “higher degrees of well-being than people who pursue only one or the other” with a higher degree of mental health, and experience more well-rounded well-being. The consensus, she says, is that people need both hedonia and eudaimonia to flourish.

This article appeared in the June 2018 issue of Mindful magazine.