“No time.” Again and again, teachers tell me this is why they can’t teach social-emotional skills to their students—and it’s no wonder given the demands placed upon them.

But while a 30-minute social-emotional learning (SEL) lesson might be impossible to fit into a week, slipping a social-emotional concept into already-existing curriculum content may not be. In one study, student teachers were paired with novice school psychologists to create language arts lessons with an SEL focus. The researchers found that the process yielded “creative and powerful” lessons and fostered a desire in both groups to continue such collaboration.

Much of the curricula in schools already has the potential to offer lessons about social, emotional, or moral issues—if educators make these connections.

We decided to try something similar at the GGSC Summer Institute for Educators—and we were astounded by the results. Much of the curricula in schools already has the potential to offer lessons about social, emotional, or moral issues—if educators make these connections.

How to integrate SEL into curriculum content

Schools that want to teach social-emotional learning but find themselves strapped for classroom time can instead take a social, emotional, and moral inventory of what students are currently learning. For example, many topics, books, people, and concepts in the curricula already involve:

- a person’s emotional life

- an ethical dilemma

- a situation calling for compassion

- a societal challenge

- the ethical use of knowledge

- cross-group interactions

- an implicit prosocial concept, such as ecosystems or the Declaration of Independence.

For example, as one of our elementary math educators pointed out, fractions underlie the practice of communities dividing resources. When students learn about the fractions of a pizza pie, they might also ask: How could the pizza be divided based on who was the hungriest?—an awesome introduction to the idea of equity.

In addition, the simple act of working on a particular lesson might bring up social, emotional, or moral challenges for students. When designing a lesson, educators can also ask questions like:

- Does the lesson involve challenging conversations that might surface a clash in values?

- Are students required to work with a partner or in groups?

- Is the assignment so demanding that students might need to attend to their emotions or demonstrate attention and perseverance?

- Do they need to exhibit self-confidence—for example, during an oral presentation—or set long-term goals, or make ethical choices?

By integrating SEL into curriculum content, educators are not only giving students opportunities to practice their social-emotional skills, but also showing them how integral these skills are in our daily lives.

Three lesson plans, transformed

After three days of providing our Summer Institute participants with a foundation in the science and practical application of social, emotional, and moral development—a critical step in the process—we asked them to create a lesson in which they integrated a social or emotional skill, a mindfulness practice, and/or a moral dilemma. Task in hand, participants went into creative and collaborative mode and came up with magnificent examples, a few of which we’re excited to share with you below.

Elementary school

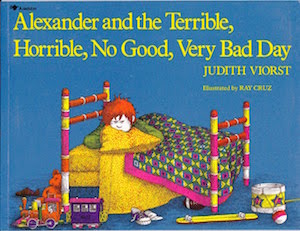

To teach younger children about cognitively reframing a situation—or changing how one views something in a more positive way—our elementary educators suggested using the classic book Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day.

The lesson starts with a mindful moment to calm and center the students so that they may better reflect on whether they have ever had a bad day. Then, after the book is read aloud to the class, students make a list of the problems that Alexander faced and attach a feeling to each of those problems. For example, when Alexander thinks his teacher likes his friend’s picture of a sailboat better than his drawing of an invisible castle, students consider how this might make Alexander feel.

Next, students choose a couple incidents from the list and discuss how Alexander could change his response to these incidents so that he feels better. With the example above, Alexander might think of a time when his teacher really liked his picture, be happy that the teacher gave his friend a compliment, or draw a castle that his teacher could actually see.

To close the lesson, students create a class book called Pretty Good Day with drawings and descriptions of something challenging that happened to them that felt less painful after they changed how they thought about it.

Middle school

The middle school science educators looked to Humpty Dumpty to help them set up lab group roles and norms at the beginning of the school year. Equipped with straws, plastic wrap, cotton balls, aluminum foil, and paper, students are given one minute to individually engineer a wall with protective devices so Humpty Dumpty won’t fall and break.

Following this challenging task, students discuss their experience and what they might change about it, cultivating their social awareness of individual versus group strengths. Next, students form groups of at least two and try the task again, but this time in three minutes. In the subsequent discussion, the teacher may bring up SEL topics such as problem-solving skills, how current choices affect the future, cooperative working, and conflict resolution.

The activity closes with the students trying the task once more in specific lab roles (e.g., project director, materials manager, data recorder, time keeper), and then reflecting on how these roles made the task easier or more difficult.

Since middle school is a developmental time when students begin questioning rules, social norms, and the like, educators could extend this lesson by asking their classes some thought-provoking questions.

For instance, why did Humpty Dumpty choose to climb the wall and why was he all by himself? Where were his friends? Was he allowed to climb the wall or was he breaking rules? Who made the rules and are they fair? And what about the stability of the wall—whose responsibility is it to make sure the wall is safe? Why might the wall not have been safe for Humpty Dumpty to climb? Finally, did Humpty Dumpty receive adequate care after he broke? If not, what might be done to make sure future Humpty Dumptys are cared for?

High school

High school educators created an interdisciplinary approach to the topic of health care in the United States. In math, students use ratios and graphing to consider the amount of federal money spent on health care per capita. Then, in history, students review the history of health care in the United States in the 18th, 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Armed with the results of their inquiry, students are then challenged to consider the larger ethical questions about health care in the United States. Is health care a moral imperative or is it a social convention? In other words, does the government have a moral obligation to provide health care to every one of its citizens because lack of health care is harmful to people, or does it provide health care only because the law says it must?

Acknowledging that these questions may surface disparate views, the educators incorporated a mindful moment into the lessons, along with SEL skills such as active listening, non-judgment, and perspective-taking.

Viewing curricula through a social, emotional, and moral lens is like a habit of mind: the more you do it, the easier it gets. Perhaps the greatest benefit of teaching lessons like these is that students will start to examine their education, their decisions, their interests, and their relationships through this lens, helping them to cultivate a more thoughtful and discerning approach to life.