One morning in early May of 2006, I sat drinking strong coffee on the patio of the Maison Dupuy in New Orleans. Feeling the sun on my skin and listening to the sound of a nearby piano, I read from Andrei Codrescu, “This is the time when the part of you that is music overcomes the part of you that is silence.”

Indeed. Sun and jazz and water falling from a fountain of stone dolphins ridden by small naked water children. Cupids with harps. Wrought iron balconies, like fine Indian filigreed jewelry. The part that is music—six months after Hurricane Katrina.

There was no way I couldn’t come to this first International Jazz Festival after Katrina—an event that almost didn’t happen this year. One of my life passions is seeking out opportunities to experience the growth, wonder, and delight of being among people who are different from me; realizing how much we humans all share in common while marveling at our differences.

New Orleans embodies this better than anyplace I know. There, a gumbo of ages, races, and ethnicities co-exist and intermingle probably better than any other place on Earth.

The energy and synergy created in this melting pot is infectious. Who can resist the intoxicating combination of music, food, and art; of Allen Toussaint and Laissez les bons temps rouler; of sweet, sticky air and the brackish breeze off Lake Pontchartrain?

The previous day’s concert was a joyous confirmation of this fact: More than 100,000 people flocked to the still-dazed city—a fierce show of support and commitment that said, Yes, we can overcome.

With a neighborly openness I came to expect there, a guy at the next table said hello and asked me what I do. When I told him I teach mindfulness, his response was immediate. “That’s not for me,” he said. “I don’t want to be mindful. I am a passionate person. I don’t want to lose that.

I wouldn’t mind being more calm and clear, but I don’t want to be dull. Anger, like now, after Katrina, gets me to act. And I love sex.”

His real passion, he told me, was music. He played bass. That’s why he had moved here.

His reaction is one I’ve heard before. There’s a perception that to be mindful means that you’re passionless, a heartless robot; that being present and aware somehow dulls the creativity and drive that someone like my new musician friend feels in his veins.

Yet a misconception is just what it is. Mindfulness actually highlights our passions, by bringing us fully into the experience of the present moment, increasing our focus on whatever is happening, allowing us to enjoy our experience with far greater nuance: the taste and texture of a perfectly ripe plum; the thrill of an Italian word rolling off your tongue; feeling the warm, soft skin of a lover.

Mindfulness helps us know who we are, and who we are not. With that comes a profound self-confidence, which opens the door to discovering our passion. We don’t become dull—hardly! Our senses become enhanced, our thoughts clearer, our reaction times faster. We can see more clearly what is calling us from amid the many fleeting distractions of our lives. And with a clear, stable mind, we are better able to find ways to balance the demands of our lives—to find a way to live with passion while also paying the mortgage.

Through mindfulness we cultivate the ability to see exactly what is there: emotions, thoughts, memories, pain, the whole catastrophe. And seeing who we are without judgment leads to acceptance, and, ultimately, to self-love. When we stop wanting to be someone else, we can finally recognize our distinct talents and passions—and what we want to do with our one precious life.

How Passion Leads the Way

Passion defined is far less interesting than its lived experience: an intense emotion or a compelling enthusiasm. At its core, it’s an appeal that drives us to invest time and energy, again and again, in order to know the object of our passion better and swim in its heady waters.

Passion doesn’t just pop up, fully formed. It emerges. It comes in hints and tastes; it’s something that makes you notice.

Passion arises in many forms. You might have passion for an activity or interest; for a particular path or way of living; and, of course, there’s the passion we can feel for another.

No matter how it reveals itself, I believe passion is an arrow, pointing us to those experiences that are about our life’s larger purpose. It hints at the things that make us unique, the preferences and interests that, despite sharing a 99.9% genetic similarity with every other human being, place us on our own distinct path.

From graduation speeches to the writings of Joseph Campbell, we are urged to follow this passion to find our true north. Nelson Mandela, whose passion for equality kept him focused during 27 years of imprisonment, famously said, “There is no passion to be found playing small, in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living.”

When Julia Child discovered her passion for French cooking while living in Paris with her diplomat husband, Paul, she changed the experience of home chefs forever.

Steve Jobs was as passionate about building tools that would help people unleash their personal creativity as George Lucas is about turning myths into movies.

And the late, great American poet Maya Angelou spoke of the passion it takes to master your craft. “You can only become truly accomplished at something you love. Don’t make money your goal. Instead pursue the things you love doing and then do them so well that people can’t take their eyes off of you.”

But what does it really mean to “find your passion”? (And, scarily, what does it say about us if we can’t readily identify ours?) Some people seem hardwired for passion—like the New Orleans bassist, they clearly know what motivates them and they heed the call.

For many of us, however, passion doesn’t just pop up, fully formed. It emerges. You get it in hints and tastes—it’s something that makes you take notice, an activity that you lose yourself in, a pursuit that calls out to you in a way that other things don’t. You might find only a small seed at first—but it will grow and flower if you cultivate it. Passion is not static.

The problem is that we are often so busy with the to-do lists of our everyday lives that we can forget what really matters to us. We might not even notice the glimmer of a calling—or forget about it as soon as our attention is drawn to something else. Our passion is buried.

This is where mindfulness is especially helpful.

Practicing sitting still or walking slowly, in silence, we reduce distractions and learn to pay careful attention to our breath or sensations in the body. We begin to increase mindful awareness, which we can then bring to everything we do. We don’t become dull or boring. We wake up to life, breath by breath. We cultivate wise passion.

The Dark Side of Passion

Passion as a motivating interest pointing us toward our bigger purpose is usually a source of joy unlike any other. Without mindful awareness and wise discrimination, however, passion has a well-documented shadow. Faust’s passion for knowledge (not wisdom) leads to a pact with the devil. In Homer’s Iliad, Helen and Paris’ passion (not love) destroyed an entire culture.

When passion is no longer compelling but obsessive, it becomes lust or greed, which can lead us to do anything necessary to get what we want or to hold on to it, no matter the consequences to us or to others. Our emotions are controlling us, rather than the other way around.

When we become attached to the emotion of passion, and desperately fear what it will be like to lose it, then we have lost touch with the spacious positive energy of passion.

We see daily in the news the suffering brought by greed for money, for land, for power over others, for fame.

We are all vulnerable to obsessive passion. We all get lost in it sometimes. The drive to earn money so you can give back to the world becomes an obsession with earning more and keeping more, and so on.

Does being mindful mean that we shouldn’t appreciate or strive to acquire beautiful or useful things? Not at all. In fact, mindfulness helps us appreciate things but not to be attached to them. (That we may find we don’t need as much as we think we do might be a welcome realization.) It helps us experience life open to each moment, with all our senses, and it also helps us cultivate evenness of mind, equanimity, and the wisdom to see that our possessions are not who we are.

We need mindful awareness so we are not driven to action by blind passion, so we have the space to see our motives and our choices and the insight to choose wisely. And we also need to cultivate compassion, so that in our drive to fulfill our own passion, we don’t cause harm to others. This frees us to engage more fully in a passionate life.

So delight in your passions. Find your New Orleans or your French cooking. Work to resettle immigrants, preserve nature, or develop solar technology. And bring mindful awareness to each moment, each action, each decision. Cultivating wise passion is the ultimate act of love; a heartfelt offering of our unique contribution to the world.

Two Mindfulness Practices for Discovering Your Life’s Passion

Bring Your Passion Down to Earth

Passions are powerful. They can lead us to do great things but also to make choices we regret. Equanimity can help.

Also called even-mindedness, it’s the experience of balance in heart and mind. It’s when you find yourself in a difficult situation, but you feel centered, calm, and able to be with whatever arises.

Equanimity keeps us moored to a steady state of being, not tossed about by the waves of emotion and change. Applied in pleasant situations, it allows us to experience even deeper fulfillment.

Practice for strengthening equanimity:

- Sit quietly in a comfortable position. Bring your attention to your breath until your body and mind feel calm.

- Notice what arises. When strong thoughts, sensations, or desires come up, instead of pushing them away—or encouraging them—try being curious. Not judging the thing, or your impulse to deny or court it. Just simply… notice.

- Keep noticing until it dissolves by itself, and gently return to the breath. You are developing equanimity.

- End your practice by repeating silently a few times: “May

I be in balance and at peace.”

We’re told again and again to live our passion. But what if we don’t know what we’re passionate about? With a little mindful investigation, your passion will start to reveal itself and point you in a direction—whether to pursue a vocation that engages you on every level or explore interests that feed your soul—that feel in alignment with your very purpose. Here are some tips for unearthing your hidden passion.

3 Ways to Let Your Passion Bloom

1) Clarify your values: What really matters to you in life? What do you believe in? What brings you the most joy or lights you up? It could be justice, exploring new places, family, or supporting the arts, as examples.

Practice: Think of an object related to your values and how it might be utilized through a vocation or avocation. Sit quietly, breathe in and out, holding the object in your mind, and see what arises. Allow its story to unfold without judgment.

Does this story point to a new activity or direction for you? Don’t be discouraged if your first answers don’t reveal a fiery passion. Keep asking, and keep listening.

2) Identify obstacles: What is in the way of living in alignment with these values? It could be lack of time, distraction, resources, or even a lack of imagination.

Practice: Contemplate that question. Listen for how to overcome them. Maybe it is a supportive community, more research, overcoming conditioning. Keep asking. When negative judgments arise—I can’t start my own business because I don’t have the skills—try using the word “yet.” I don’t have them yet.

3) Remember your superpowers and develop your skills: What do you do really well, and is there space for you to do it? When you ask this of children, they can tell you without hesitation. My granddaughter Dahlia tells me: “I am a good artist—I just drew a portrait of McKinley (the cat). And I have a good voice—I can sing. And a good memory—I remember the words.” I wish I could see into the future and see if she brings those talents into whatever work she finds.

Practice: Imagine yourself as a child. What did you love to do and what did you know you were good at? Let images arise. Remember how it felt. Is it still true? What else is true now?

And then identify the skills you’ll need to bring that latent passion back to life.

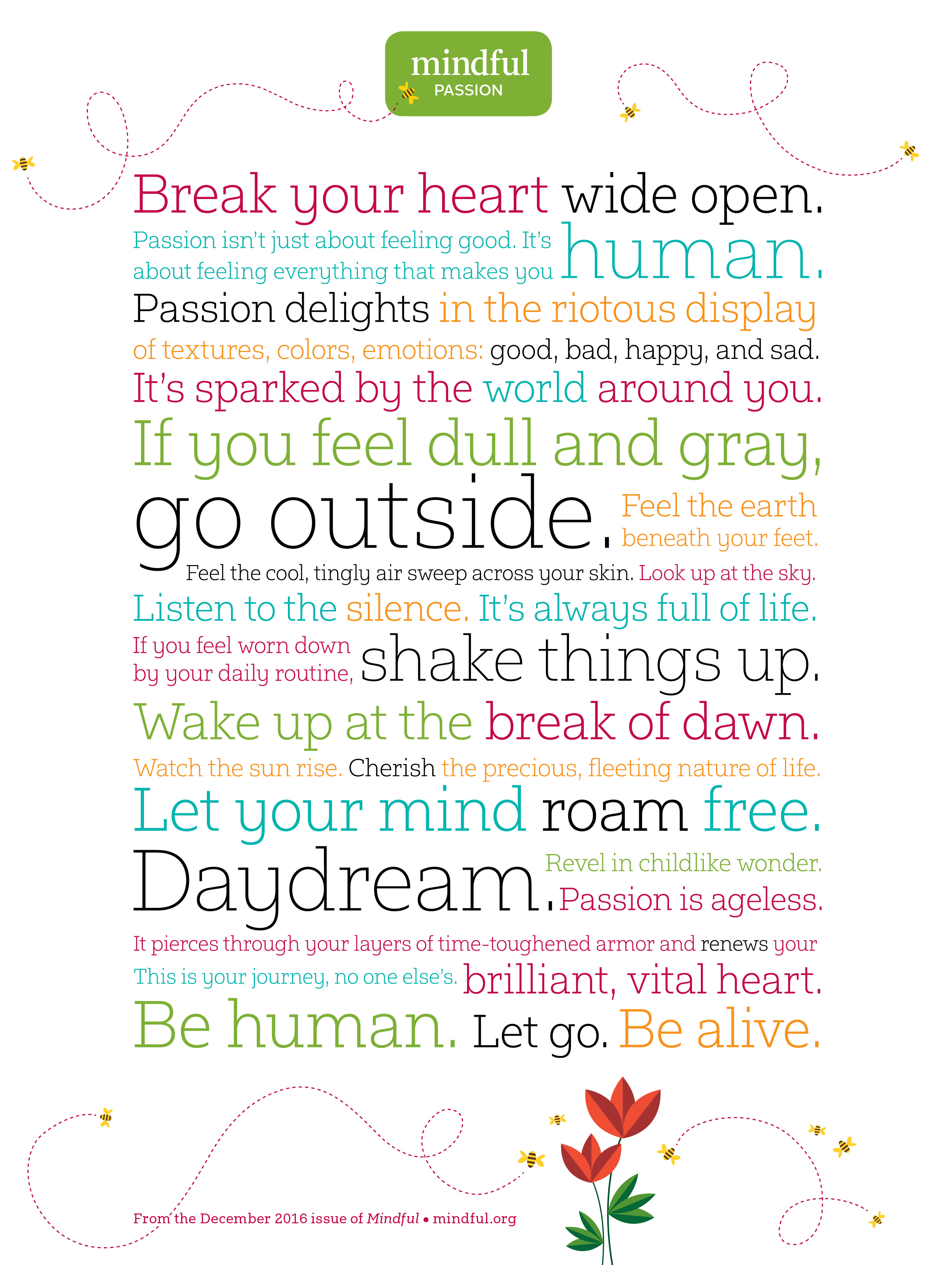

Exploration: Passion Manifesto