Mindful: I found it refreshing how your book is much more a personal journey than I expected, as much about you as it is about the people you cared for.

Bronnie Ware: I had a lot of requests from people to write a memoir of my own, so I was able to merge them together. In hindsight I think I would have changed the title. It’s been translated into several other languages and in some countries they won’t print it with “dying” in the title, because people won’t buy the book. In Portuguese it’s called Before I Leave and in Dutch it’s If I Could Live My Life Over Again. In a way, they’re probably a bit more true to the storyline. You live and learn.

MF: How long were you in personal care work?

BW: Eight years.

MF: When did you start to notice patterns in what your patients were telling you?

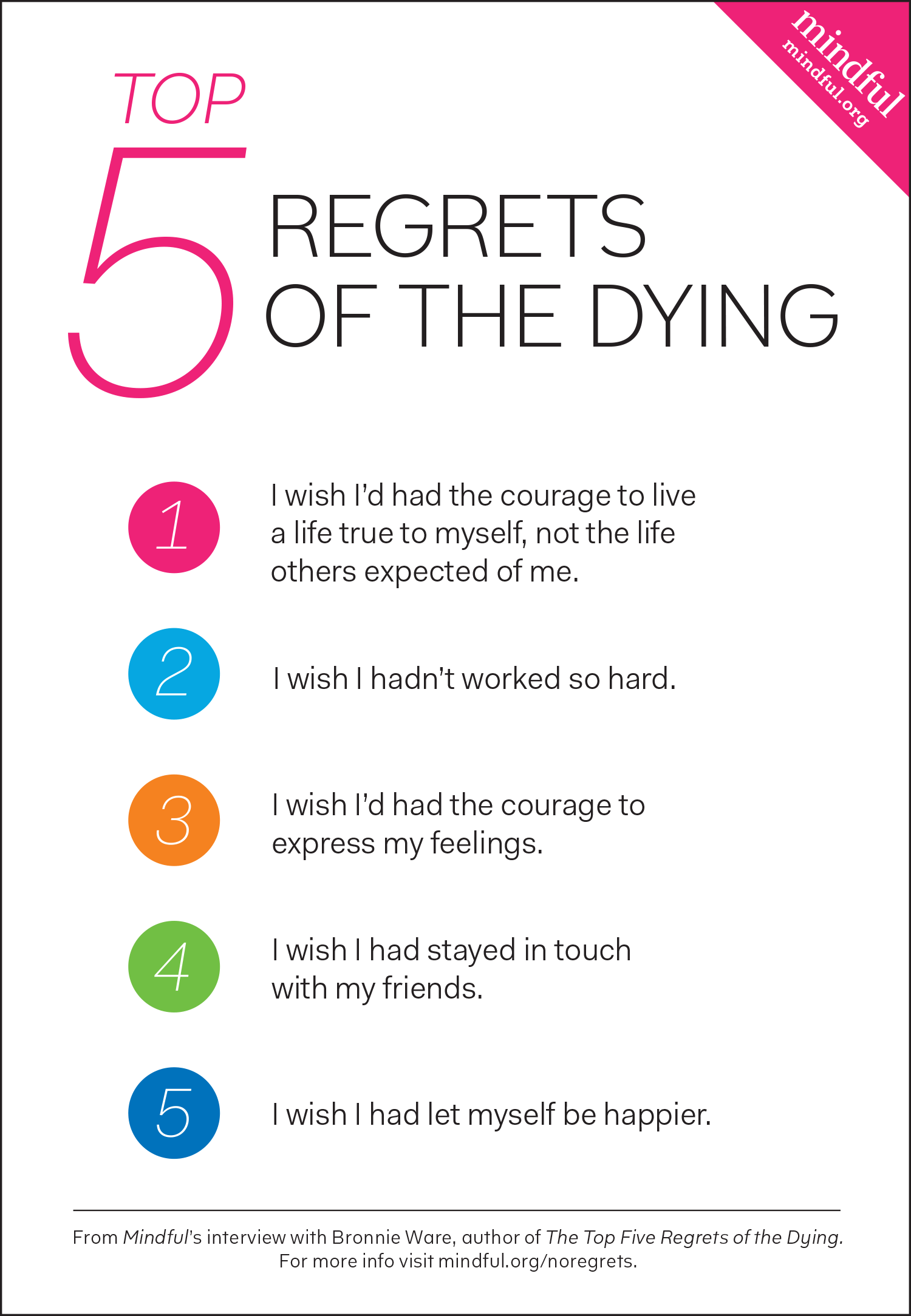

BW: Certainly within the first year. That first regret—”I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself”—that kept coming up.

MF: In your book, the person who really encapsulated that first regret was Grace. You managed to get quite close to her. Can you tell me what that experience was like and what you learned from it?

BW: She was a woman who was in so much pain for not having given herself the life she wanted. It had a very profound effect on me. And she also made me promise, before she died, that I would live a life true to myself. I didn’t take that promise lightly. I knew that no matter how hard it would be to stay true to my own path—and it does take courage to do that—nothing could be as painful as lying on your deathbed with that regret. I was seeing it first hand.

MF: And you saw it in other people you were working with.

BW: I saw it over and over. Grace was the first one, and I came to see it regularly and I came to expect it.

MF: The number two regret was “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.” I understand that was largely a sentiment of men you cared for. But I wondered, that feeling of not having lived a life true to oneself, was that something you heard more often from women?

BW: When I think about it, it was more from women. A lot of women in the older generation weren’t living the life they wanted, they were living the traditional homemaker role, really being subservient to the breadwinning husbands.

MF: What else do you think might be specifically generational, in the regrets that you observed people having?

BW: These days a lot more people have counseling and therapy. I don’t think we’ve mastered expressing our feelings completely, but I think the younger generations have learned to open up more. I think the third regret, “wishing I’d been brave enough to express my feelings,” hopefully that won’t be as common now.

MF: And I wonder if the Internet might prevent the fourth regret (“I wish I’d stayed in touch with my friends”).

BW: Hopefully, as it is harder now to lose track of friends. But, having said that, I’m in my mid-40s and I get emails from a lot of women in their 40s. My book has inspired them to reconnect with friends, to write to their friends and tell them they love them. Despite Facebook and everything else, they have let those friendships slip by. It still happens.

MF: In what surprising ways have people who’ve read the book reached out to you?

BW: It’s actually been a relief more than a surprise. I ended up burning out. I looked after dying people for eight years and I really needed some time to look after me. Because I’d been so focused, and used so much strength honoring my own path to being an artist and my promise to Grace, the reason it brings relief is because it shows me I could get my message out there, even if it wasn’t to be through songwriting. [Ware is also a musician]. It means all those moments of wisdom shared with dying people wasn’t only for my benefit. I’ve been given the opportunity to share that with a huge audience. It’s heartwarming to realize how similar we are despite cultural differences. The amount of people who’ve found my work resonating with them, it’s been phenomenal.

MF: I understand you have a meditation practice. Can you tell me how that’s impacted your life?

BW: I learned through meditation that compassion starts with yourself. It was my biggest lesson: self-love, to be gentle with myself. I was suicidally depressed. I couldn’t have survived without meditation. It just taught me to celebrate my vulnerability and my humanness, and to realize how much was not about me. We all get conditioning from family, peers and society. Compassion really allowed me to have compassion for myself and for other people. I was working at a birth center for a little while at the same time I was working with the dying, and that taught me to see everyone as the baby they once were, with that innocence and vulnerability we’re born with. Compassion has really allowed me to detach from other people’s stuff. I just have to look after me and love me.

MF: Those lessons must have been helpful in hearing the troubles of those who were dying.

BW: Yes, it taught me not to judge. I had compassion and respect for whatever that life had been like. I think regret is a very harsh judgment on yourself. The dying people who were expressing regrets to me already had their own judgment. They certainly didn’t need mine. Through meditation I also learned mindfulness and being very present with the people. That’s probably a large part of why our relationships became so personal. When you have a listener that’s obviously present and truly listening, it does give the person permission to open up. And it wasn’t just the dying people I was looking after, it was the family dynamic. All the stuff that comes up for the family being left behind, there’s some truly irrational behavior, a lot of fear and drama. I think meditation really helped me stay calm. I was often the unofficial mediator in the family, and I think meditation is the key to my success in that role.

MF: Do you think meditation is a route to having fewer late-life regrets?

BW: I think if you can develop compassion for yourself, you’re not going to have regrets. Rather than judging yourself for something you did or didn’t do and having regrets about it, you can actually look back on it later with compassion for who you once were. I think in our busy lives, without meditation, it’s very easy to be ruled by your busy mind, by fear and others’ expectations. I think once you do connect with that part of yourself with a regular practice, there comes a time when your heart speaks too loudly for you to ignore.

This web extra provides additional information related to an article titled, “Building a Regret-Free Life,” which appeared in the June 2013 issue of Mindful magazine.

read more

How to Talk to Your Kids About Death

When your child asks about death, it’s often difficult to find the right answer. Providing a safe space that allows kids to explore their feelings can help ease anxieties—for both them and yourself.

Read More

Transform Your Fears Mindfully

The only way through your fears is to get comfortable being uncomfortable.

Read More