Imagine this scenario. Harry wakes up on a typical workday, a Wednesday, in a mood—a frighteningly intense mood. A free-floating anxiety courses through his body, making him edgy and angry. When he gets up and goes into the kitchen, he hears his roommate opening a bag of chips to put a handful in his brown-bag lunch. The crinkling of the chip bag sounds like the roar of a jet engine to Harry; it’s that irritating. He wants to scream at his roommate to quiet down and just go away, now.

He keeps it together enough to let his roommate get on with his day, but these feelings scare Harry. He feels he may be losing control altogether. How can he concentrate? How can he work with others? Perhaps he should just go back to bed and curl up in a ball, but no, he’s been there before. That could take him in a downward spiral of indeterminate length, a deep, dark funk.

Harry stands there frozen in the kitchen, teetering uncertainly between alternative versions of hell, barely able to find a sliver of stable ground to walk on. He holds his head in his hands and starts to cry. He wonders yet again whether life is worth living. His friends and family and coworkers will react with a familiar surge of pain and fear when they eventually hear his latest tortured cry for help. In two days, his ten-year-old son will be coming for his biweekly weekend stay—or not. Harry’s pain will soon be rippling widely.

• • •

Harry’s story is based on a real person. His name has been changed and some details altered to preserve anonymity. It’s a story that is not unlike that of many people dealing with mood disorders and depression. It may resonate with your own experience, since we have all felt ourselves lose control of our emotions and moods, fearing that any form of equilibrium would elude us. We know people who do battle with fluctuating moods on a regular basis. Some are on medication, some are hospitalized, and some are using methods and developing skills to supplement or substitute for medication or therapy.

Because we know people by name—people who are our friends—or because we have grappled with an uncontrollably wild and potentially destructive mind ourselves, we think of these mental challenges and disorders as personal problems. But when you add up all the people going through this personal problem, you end up with a problem for all of us, a public health problem. It’s like traffic. It’s a personal problem when I can’t get to work on time, but the traffic that’s tied up every day citywide, eating up gas and causing pollution, is a problem for all of us, and we have to take it on together. Our collective mental health is one of those big traffic jams we need to look at from a larger perspective.

According to the National Institutes of Mental Health, in 2014, an estimated nearly 16 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States had at least one major depressive episode in the past year, approaching 7% of all US adults. And close to 10% of adults in the country are affected by mood disorders generally, more than the population of greater Los Angeles. And these are not just people having a rough day. Living with deeply unstable moods takes a toll. The World Health Organization estimates that depression is the leading cause of disability for people in midlife and for women of all ages. The most common approach for those who seek treatment for depression is anti-depressant medications, whose usage in the US doubled between 1998 and 2010 and increased fivefold from 1988. Of women in their forties and fifties, an estimated 23% take antidepressants.

Mindfulness has been demonstrated in many contexts to help people with mental illnesses and post-traumatic stress. The evidence base is small and the scientific study is in its infancy, but having practiced mindfulness meditation most of my life, I’ve come to believe that the habit of taking time to be with oneself and pay simple attention to what’s going on in your mind and body can be a powerful way to come to understand your emotions better, and to ride and regulate them. While I’ve never thought meditation brought instantaneous magical powers—such that someone like Harry, writhing in mental anguish in his pajamas in his kitchen, could simply sit down, meditate, and have his troubles go poof—early scientific evidence and anecdotal reports of meditators lead one to wonder whether mindfulness could be a means to provide mental healing and stability for the many millions of people suffering depression, other mood disorders, and mental health challenges generally. Could mindfulness, in fact, be the future of psychotherapy?

To take on this question I talked with two clinical psychologists and researchers who care deeply about mindfulness and therapy. In fact, Zindel Segal and Sona Dimidjian had recently finished a paper on the prospects for ongoing scientific study of mindfulness-based interventions (published in the October 2015 issue of American Psychologist). They asked what it might take for mindfulness to have a lasting impact on public health within our mental health systems, and in particular what kind of scientific research would be required. Segal is one of the developers and founders of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) and Dimidjian, who has taught MBCT for many years, including together with Segal, has collaborated with him to create Mindful Mood Balance, a program they are piloting that would allow people to take MBCT at a distance, using their phone, tablet, or computer.

In 2014, nearly 16 million adults aged 18 or older in the US had at least one major depressive episode in the past year.

Among his several distinguished positions, Segal is the Director of Clinical Training in the Graduate Department of Clinical Psychological Science at the University of Toronto Scarborough, so he is intimately involved in the training of a next generation of mental health clinicians. At our first lunch, down the street from the U of T, he wanted to talk about mindfulness not as something that would “replace” therapy and existing therapeutic methods and systems, but that would leverage the power of therapy by providing another “skills-based” approach with results supported by research. Segal is a great interlocutor, which is no surprise, since cognitive therapy is all about an inquiring dialogue about what’s going on in your mind. He began a little rhetorical conversation:

“What is therapy really good at historically?”

“Insight.”

“But are insights enough?”

“No, for real sustainable change to happen, the insights need to be married to skills that can be put into action—successively. And that is something mindfulness provides par excellence. We all love that moment of insight, and it keeps people coming back to therapy sessions. But the working-through part, where you encounter a challenge again and again and learn to embrace it, nonjudgmentally, that’s where you put the insights into effect in your life.”

Segal points out that he did not come to mindfulness as part of a personal life quest, so he doesn’t feel any need to proselytize for the practice. He came to it as a researcher and clinician hoping to find ways that more people could get better. In particular, his work focused on the problem of how people who had recovered from depression could still relapse easily if something triggered a sad mood, which in turn would bring on feelings of inadequacy—the downward spiral of depression. “The experience of depression can establish strong links in the mind between sad moods and ideas of hopelessness and inadequacy,” Segal told Sharon Begley for the book Train Your Mind, Change Your Brain. “Through repeated use, this becomes the default option for the mind.”

Finding means and methods that might interrupt that “default option” became Segal’s paramount concern, and starting in 1992 it brought him to a collaboration with John Teasdale and Mark Williams, both of Cambridge University at the time. If mindfulness practice did indeed provide the kinds of skills in working with thoughts that advocates claimed, this form of meditation—particularly as carried out in a secular, regularized program like Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction—could be powerfully combined with cognitive therapy. Many had long regarded cognitive therapy as the gold standard treatment for depression. A skills-based approach, it asks patients to inquire into, familiarize themselves with, and redirect the thought process that is getting them into trouble (cognitive distortions, or what some people call “negative self-talk,” or “stinkin’ thinkin’”). It takes close attention and stick-to-itiveness to make it work, which is why a practice that allows one to develop the habit of seeing thoughts without immediately reacting could be an ideal adjunct to the cognitive practice—and in fact create a hybrid that is more than the combination of the two. When CBT meets mindfulness, the emphasis shifts from changing or fixing the content of our challenging thoughts to becoming more intimately and consistently aware of these thoughts and patterns. The awareness itself reduces the grip of persistent and pernicious thought loops and storylines.

Segal, Williams, and Teasdale collaborated to create an eight-week program modeled on MBSR. Jon Kabat-Zinn—who developed MBSR—had some initial misgivings about the program, fearing the curriculum might insufficiently emphasize how important it is for instructors to have a deep personal relationship with mindfulness practice. Once he got to know the founders better, he became a champion for the program. In 2002, the three published Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression: A New Approach to Preventing Relapse, now a landmark book. MBCT’s credibility rests firmly on ongoing research. The MBCT website currently lists 11 key research papers. Chief among them are two randomized clinical trials (published in 2000 and 2008 in The Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology) indicating MBCT reduces rates of relapse by 50% among patients who suffer from recurrent depression. Recent findings, published in The Lancet last year, show combining a tapering of medication with MBCT is as effective as an ongoing maintenance dosage of medication.

As is typical for mindfulness-based interventions, no overarching body governs MBCT, but a number of very qualified senior teachers have taken it on since the program was founded, and centers in Toronto, the UK, and San Diego offer professional training and certification. Thousands of people are taking MBCT at any given time and hundreds of teachers are offering it. It’s popular now not just with people who have been diagnosed with a mood disorder. Many people find the inquiry into thought processes and the reinforcement of habits powerfully helpful. One program in Toronto, for example, serves members of the arts community.

Like MBSR, the eight-week program occurs in two-hour weekly classes with a mid-course day-long session. It combines guided meditations with group discussions, various kinds of inquiry and reflection, and take-home exercises. “Repetition and reinforcement, coming back to the same places again and again, are key to the program,” Segal says, “and hopefully people continue that into daily life beyond the initial MBCT program, in both good times and bad.”

Over the past several decades, Segal has become a dedicated mindfulness practitioner and a strong believer in the efficacy of regular practice, which is why he is skeptical about mindfulness becoming rapidly integrated into the institutions that train clinicians. “I could not just suddenly inject meditation into the clinical training program I lead. It’s not as easy as that. If a clinician wants to bring mindfulness into their clinical practice, they are going to need to develop and maintain a regular practice themselves. That’s a big commitment. How do we keep track of that? How do we measure that in the context of a professional training institution? Being a young aspiring clinician and knowing a little something about mindfulness is one thing. Being able to lead, model, and train patients in it is another matter altogether.”

Right now, it is safe to say that in any local mental health community, many of the psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, nurses, and support staff would have heard of mindfulness, some might have a little experience and know a bit about it, but few would be trained to offer MBCT or MBCT-like therapy to patients. In some centers, it is more widely available than others, but it is not integrated into the mental health system. That day is a long way off. Segal guesses that, over time, many therapists will have mindfulness as an element in their therapeutic practice. They will have a certain amount of personal experience and will be able to follow protocols for providing some mindfulness practices to their patients. Others will have it as something they offer in a very robust way or as their sole or primary offering. This is how it is now, at a small scale. For it to grow much bigger—with integrity maintained—Segal says, “It needs to be professionalized, with a widely accepted standardized accreditation that consumers could trust. Right now, it’s pretty easy for someone to offer MBCT. That’s been good enough for this birth period, but for mindfulness to be fully accepted as a mainstream intervention, more rigorous monitoring and standardization of the training will be required.”

But there might be ways to reach more people who need help sooner…

• • •

Helping to build the field of mindfulness-as-a-mental-health-option for a greater number of people is not an academic exercise for Zindel Segal. And neither is it for his close colleague, Sona Dimidjian. As I sit down with Dimidjian for breakfast in Boulder, Colorado—where she is a professor in the Department of Psychology and Neuroscience at the University of Colorado—her voice and manner exude caregiving. Dimidjian came to mindfulness first as a teenager, but her passion for it really took root in 1999 when she was a grad student at the University of Washington. Her advisor was set to give a keynote address at a conference, and he simply didn’t show up. He had died of a heart attack. “That incident began what was very painful time for all of us who worked together with him, and for his family. It brought me back to meditation practice in a very concentrated way.”

It also brought her to look at MBCT, which was in its early stages at that point, and to “track down” Segal at a professional meeting and tell him “I need to learn this.” He agreed to supervise her at a distance, over time they grew to be colleagues, and now the two have taught MBCT together many times, including to a group of people who agreed to have their sessions filmed for the web-based Mindful Mood Balance program.

Depression is the leading cause of disability for people in midlife and for women of all ages, The World Health Organization estimates.

Dimidjian and Segal are mutually committed to two main principles: scientific rigor and caring for the most number of people possible. These two interrelate: Scientific validation leads to more popular acceptance in public health institutions. They also conflict: Good science moves slowly.

Recognizing this, like others, they have been moving on both fronts: promoting good science, while keeping a laser focus on the needs of the millions of Harrys out there. For several years, they worked on the landmark paper mentioned above, “Prospects for a Clinical Science of Mindfulness-Based Intervention.” When a field becomes trendy, there’s a whack of studies, but after a while you have to ask, “So, where is all this going?” It’s one thing to study the hell out of something (think of all the research you’ve heard about wine and coffee); it’s another thing entirely to effect real change in how we live.

They surveyed the voluminous number of studies of mindfulness-based interventions and mapped them according to a National Institutes of Health model of stages of research that charts the course of research from basic research (identifying the nature of disorders to be treated), through research that establishes efficacy (a given treatment works in a controlled setting), through to effectiveness, implementation, and dissemination (the treatment can actually reach people in need through existing or newly developed delivery systems with minimal decrease in quality and efficacy).

There are many pitfalls and dead ends in the pathway from lab research to widespread adoption. Many promising ideas never find their way into adoption in the real world. For example, a pilot program for increasing nutrition in public schools may report astounding results, but can it be made to work for the 50.1 million public school students in the US?

In short, taking something that works on a small scale and making it work on a large scale is the ultimate public health challenge.

What Segal and Dimidjian recommend for mindfulness-based interventions is to take “a pause in the forward movement” of the large amount of research on mindfulness, to identify the biggest obstacles to reaching unmet health needs. “Simply accumulating a greater number of the same types of studies” without identifying the real gaps is unlikely to advance the field. One challenge in the research is controlling for teacher/trainer quality and methodology. The range of trainer styles and methods and abilities is mind-boggling, not to mention the possibility of trainers injecting personal belief systems into their work. Another is following up on participants and seeing how much mindfulness practice—the “dosage”—is effective and how much it is sustained over the years. These are tough problems if you’re trying to make general statements about learning mindfulness.

If the research program doesn’t step up to a new level, mindfulness could easily remain, as Dimidjian said to me, “a boutique-ish intervention offered by a handful of people to small populations. If it doesn’t have the capacity to have broad impact, it’s not a public-health intervention—like seatbelts or penicillin. Our work as clinical scientists addressing unmet mental health needs is not finished until we figure out how to make treatments as effective for the many as they are for the few.”

Early on in her work with MBCT, Dimidjian saw the difficulties that pregnant women and young mothers experienced in gaining access to a program like this. They’re too busy, and yet they are at very high risk for depression if they are among the many who have experienced depression in the past. This opened a whole area of applied research for her (see a report on her work with pregnancy and motherhood and depression by parenting columnist Heather Grimes). But it also helped her to think about how technology could be used to reach more people where they live.

The ubiquity of the web and smartphones and tablets led Segal and Dimidjian to obtain a grant to develop a web-based version of MBCT. They spent several years on this project in partnership with a commercial developer, Mindful Noggin. Mindful Mood Balance is the result. MMB aims to serve the same target group as MBCT. As Dimidjian says, “It’s not intended for, nor has it been tested for, people when they’re in the depths of an acute episode of depression. Its aim is to prevent relapse and help people work more skillfully to reduce residual depressive symptoms.”

MMB is not publicly available, and probably will not be for some time. Segal and Dimidjian are committed to studying its effectiveness and refining the understanding of whom it is appropriate for, before it’s introduced in a widespread way. So far, they have conducted a study in conjunction with Kaiser Permanente Colorado Institute for Health Research with 100 subjects. It showed “significantly reduced depressive severity, which was sustained over six months, and improvement on rumination and mindfulness,” according to a paper in Behaviour Research and Therapy. The same work was also reported on in the Journal of Medical Internet Research. A form of MMB has also been made available to clinicians, to enable them to test drive it and offer critique.

My press pass enabled me to obtain entry to MMB to get a feel for what an in-person mindfulness-program would be like transported to my iPad. The program follows an arc from simply learning to pay attention at the beginning, through encountering difficulties, to developing plans and strategies for preventing relapse. It is clearly intended to leave you with tools for life, and you can return to your toolkit online anytime you want. To make it personal and interactive, you have a chance to type in questions and receive answers from instructors. These Q&As are preserved, and you can see other people’s questions and how they were answered. The meditation instructions are offered by video and audio. You get mindfulness homework that you’re asked to report on, and with some very dynamic animations, you are asked to inquire into what’s happening with your thoughts and emotions in your body.

Metaphor and poetry also figure prominently. When considering that your thoughts might be like passing clouds, you are looking at passing clouds. The experience engages you in the same way as a video-game—except the rooms you navigate are in your mind and body and surroundings. What is most surprising, though, is how effective the videos of group inquiry can be. I really felt I came to know the nine people taking part in the MBCT program that was filmed for MMB. I empathized, and I saw myself in them. I came away suspecting that some interaction with live people would be needed to fully support ongoing practice, but MMB felt like what Skype has done for so many families: it closed the distance. I felt I was there.

When I talked with Segal about MMB, he emphasized that “Sona and I are committed to striking the right balance between increasing access to mindfulness-based clinical care and ensuring the integrity of what is taught. We’re trying to find ways to support ongoing practice with technologies that may not resemble the traditional teacher–student interaction.” Dimidjian told me that while they are willing to use “disruptive technologies”—think of how Internet banking or online shopping have changed how we live—to make wider dissemination possible, they must take great care. “As clinicians we are bound to an ethical code to not do harm, to ensure that we can be bridges for clients, not barriers, to not go beyond our expertise, to test and refine, and to acknowledge our limits when we see problems that are better served by someone else in another way.”

Segal and Dimidjian are cautious and visionary in equal measure. Mindfulness, Dimidjian says, could definitely become an important element in raising mental hygiene for all of us: “We do not prioritize daily practices to protect mental health, well-being, and safety the way we do practices for physical health and safety, like brushing our teeth, exercising, and wearing seatbelts. We’re at a point of learning about daily practices that can help protect our mental health and well-being. Once we’ve identified those practices and how they are effective, we need to find out what’s going to be required to make those commonplace, routine parts of daily lives in a really broad way.”

• • •

Is mindfulness the future of therapy, in particular for mood disorders? In strict terms, the answer is no, since it is foolish to think that there is THE future of anything. When it comes to human beings and what ails us, you can forget about silver bullets, one-size-fits-all solutions. “Mood disorders are complex phenomena,” Dimidjian says. “Even the word depression does not mean one thing. It’s a very broad thing. Effectively treating and preventing it is not going to boil down to one solution. You need a portfolio of options, targeted to the needs of individuals and communities. Good science is clear about boundaries: this treatment works for these kinds of people under these conditions.”

At present, if Harry, trembling in his kitchen, is lucky, he can reach a mental health professional whose toolkit includes access to proven mindfulness-based programs, covered by insurance, and maybe someday he might have something on his phone that would truly prevent a relapse. It might change his life, and the life of his son, and all those in his tribe.

If he is not so lucky, who knows?

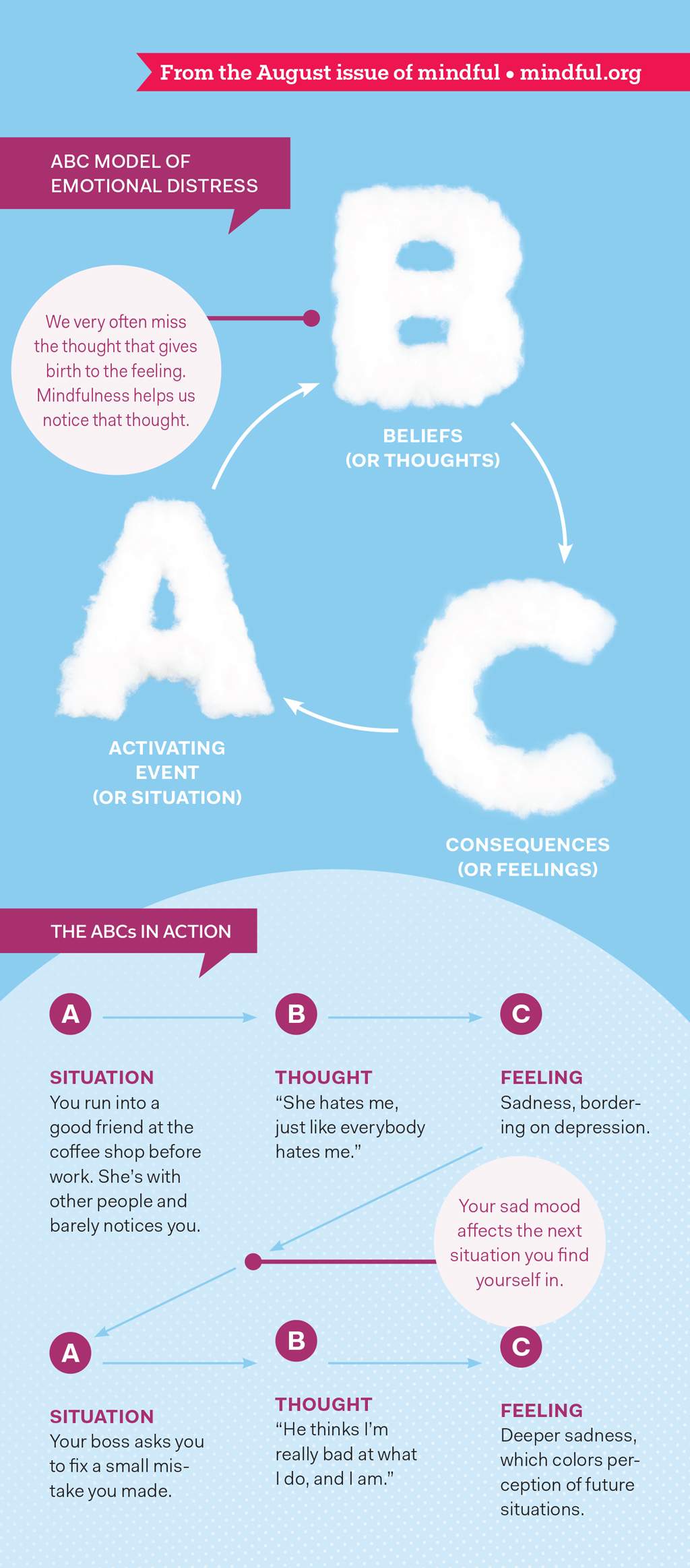

The ABCs of Thoughts and Feelings

How do we so suddenly find ourselves trapped inside a painful mood? Let’s take a closer look.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is noted for developing the ABC model of behavior. One of the many versions of the model posits an Activating Event (an event or experience that sets off the cascade), Beliefs (we evaluate what we’ve experienced, either rationally or irrationally), and Consequences (what happens in our mind, or our emotions, or action we take as a result).

The ABC model is an important part of MBCT. As it says in Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Depression, in “the ABC model of emotional distress,” the main point is that “our emotions are consequences of a situation plus an interpretation.” We find ourselves in emotional distress—we’re screaming at our spouse—and we’re clueless about how we so suddenly got there!

We start with a SITUATION (A). And end up with a FEELING (C). But often we miss the THOUGHT (B) that links them.

So, how does that happen? Automatic emotional reactions occur because we have a running commentary, a steady stream of thoughts that we barely notice if at all. And these thoughts dictate how we end up feeling. For example:

A: You run into a good friend at the coffee shop before work. She’s with other people and barely notices you.

B: You think, “She hates me, just like everybody hates me.”

C: You feel sadness, bordering on depression.

But it doesn’t end there. It’s a cycle. Now that you are in a sad mood, it may color your perception of the next event you encounter when you get to work. Your boss asks you to fix a small mistake you made, and before you know it, you are at C, deeper sadness, skipping over the interpreting thought, “He thinks I’m really bad at what I do, and I am.” By the time our friend texts us to say, “Sorry I didn’t get a chance to say hello. I was tied up in a conversation about my career,” we’ve already been caught in a very low mood all day.

Mindfulness’ strength is in helping us to see B more clearly, by giving us the room to not be so quickly reactive. And over time the event does not have to jump to emotional distress, like a grasshopper leaping over a stream.

Practice: 3-Minute Breathing Space

The three-minute breathing space is one of the core practices taught and repeated throughout Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. It’s intended to help bring formal mindfulness practice into moments of everyday life. It’s considered the most important practice in the program.

Preparation: Begin by deliberately adopting an erect and dignified posture, whether you are sitting or standing. If possible, close your eyes. Then take about one minute to guide yourself through each of the following three steps:

1 – Becoming Aware

Bringing your awareness to your inner experience, ask: what is my experience right now?

What THOUGHTS are going through your mind? As best you can, acknowledge thoughts as mental events, perhaps putting them into words.

What FEELINGS are here? Turn toward any sense of emotional discomfort or unpleasant feelings, acknowledging their presence.

What BODY SENSATIONS are here right now? Perhaps quickly scan your body to pick up any sensations of tightness or bracing.

2 – Gathering

Now, redirect your attention to focus on the physical sensations of the breath.

Move in close to the sense of the breath in the abdomen… feeling the sensations of the abdominal wall expanding as the breath comes in…and falling back as the breath goes out.

Follow the breath all the way in and all the way out, using the breathing to anchor yourself in the present. If the mind wanders away at any time, gently escort it back to the breath.

3 – Expanding

Now, expand the field of your awareness around your breathing so it includes a sense of the body as a whole, your posture, and facial expression.

If you become aware of any sensations of discomfort, tension, or resistance, take your awareness there by breathing into them on the in-breath. Then breathe out from those sensations, softening and opening with the out-breath.

As best you can, bring this expanded awareness to the next moments of your day.

Adapted from The Mindful Way Through Depression: Freeing Yourself from Chronic Unhappiness by Mark Williams, John Teasdale, Zindel Segal, and Jon Kabat-Zinn. Reprinted by permission of Guilford Press. Visit the authors’ website at www.mbct.com

Personal Stories — What MBCT Does for Me

Howard: 60, Self-employed

I have Tourette’s, anxiety, depression, OCD. I’m a poster boy for mood disorders. I’ve done a lot: medication, exercise, talk therapy, CBT. I’ve been looking for the silver bullet. I’ve always been a catastrophe, but lately I’ve been able to see those thoughts as just thoughts and I managed to come out of my depression and anxiety. That’s when mindfulness started to become really effective. Instead of it being a challenge—something I didn’t look forward to—it became my friend. At some point, I stopped looking for the magic bullet. I have a toolkit.

Elizabeth: 43, Emergency Physician and Psychotherapist in Training

I had been suggesting to patients that they check out mindfulness and see if it was beneficial for them. After a while I realized maybe I should check it out and see if it was beneficial for me! Back in medical school I suffered from depression. You come into contact with so much trauma and death and you don’t really have much guidance to help you through very emotional situations. I had a lot of rotations in oncology. It triggered a depressive episode and I started on antidepressants, which didn’t work out that great for me. It made me feel horrible. Eventually I was able to get by without them. I went to a bunch of talk therapy but, frankly, that was very thinky. And what I needed was to be less thinky. Mindfulness helps me do that. You can watch yourself really wanting things to be different, and if you stick with it and keep exploring, it goes away. Passing clouds. Sometimes things are really hard but if you stick with them they change and you gain something beautiful. This practice has made me a better boss. I’m less reactive and I can notice when my personal agenda is getting in the way.

In one of my MBCT sessions we were doing movement. I was distracted and having a hard time pulling my attention into moving. Then I noticed one of the instructors standing by the window. He didn’t seem to be sticking with the program. Then I noticed he was trying to get a lady bug that was crawling up the window to fall into his hand. He succeeded and he walked the lady bug to the other side of the room and put it in a planter. Technically he wasn’t where he was “supposed to be” but he certainly was in the moment. That’s real mindfulness. It’s not about playing by the rules, it’s about compassion.

Marika: 33, Child Psychologist

What I love about MBCT is the whole structure. It starts with a focus on attention, and then moves to training in emotional awareness, and ends with building skills for life. Mindfulness allows you to shift modes of mind, which is an incredible skill to acquire, because getting stuck in one way of thinking can get us into all sorts of trouble, right? It’s very helpful if you can shift out of a frustrated problem solving mode and just appreciate what’s happening. That can prevent the spiral down into depression.

Sally: 53, Marketing Researcher

What’s attracted me to mindfulness is that it’s not theoretical. It gives me strategies. I like listening to other people in MBCT and hearing what’s going on in their lives. That kind of just-talking is a great thing—so helpful. Mindfulness is adaptable. I’ve been able to find ways to bring it into life that work for me. When I’m on the subway, I will just sit still sometimes and take in the clickity clack of the train on the tracks. I’ve always been a worrier, a what-if person. What if this, what if that… now instead of spinning I can breathe through it. That’s had a huge impact—even though it’s just a small thing—on my ability to cope.

Joseph: 34, Musician

About five years ago, I was in a really bad place. For years, therapy had been just talking for an hour and the therapist listening. But when I left the office I had no methods, just advice—no intervention. When I took MBCT, it was the first time I was given the power to understand what’s happening with my thoughts and therefore help myself. I believed my thoughts were me, totally. Now, I can be in a more, you might say, neutral, objective position. I don’t have to be carried away by emotions and thoughts, not overthrown by mood. It’s not a cure. I still get depressed, but the practice allows me to handle it, to get over it, and let it pass. How can something so simple help you deal with something so complex as depression?

I like practicing with others. I find it hard to do myself. Today no one else showed up for my regular sitting group. I decided to do it anyway. Almost the whole sit was about not wanting to be there, tensing up, sensing the guilt I’d feel if I quit, and then that finally subsided. I was just sitting there, observing.