Stress has a huge impact on our society. Mental health problems cost the British economy around £100 billion a year, and seven million UK adults are so tense they’d qualify for a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Many of the physical ailments that overwhelm our health services are also stress-related—whether we suffer from heart disease, headaches or high blood pressure, our fast-paced lives tend not to be good for us. We want to be happy and well, but despite all the technology of our modern world, not many people find real peace.

Perhaps that’s why psychology and healthcare experts are turning to a strategy developed in a much earlier age. Mindfulness meditation has been around for over 2000 years, and courses which teach it are springing up everywhere. As we describe in our book The Mindful Manifesto, this is largely because a growing body of scientific research shows that mindfulness can make a real difference to people’s quality of life. Studies have found that mindfulness training can protect people from depression, reduce their stress levels, help them manage chronic pain, let go of compulsive behaviours like smoking and over-eating, and even enable them to cope better with cancer and other serious illnesses. Mindfulness has also been shown to boost the immune system, and induce changes in the brain that are linked to better moods. Academic papers detailing its benefits are now published in their hundreds every year.

The practices taught in mindfulness courses have been adapted from Buddhism, but are presented in entirely secular terms, as a form of psychological aid. They have therefore escaped the religious, new-age or hippie connotations that sometimes put people off meditation. This is largely thanks to Jon Kabat-Zinn, an American medic who became convinced that mindfulness could help patients with chronic health problems, especially when they had come to the end of the road with conventional medicine. It wouldn’t cure them, but might it help them deal better with their pain, and their stress?

Kabat-Zinn created a program called mindfulness-based stress reduction, which teaches meditation without any “religious” language or iconography. He then set about testing his course scientifically, proving that it could help with everything from pain to psoriasis. Above all, he showed that MBSR can indeed reduce people’s stress—giving patients something they don’t usually get from their doctors—a way to work with their minds.

The results can be dramatic—people who have battled with health problems for years find relief through accepting and working with their condition in a new way, dropping the desperate struggle to make things different from how they are. Mindfulness training makes it possible for a different kind of healing to take place, creating an open space of awareness from which people can start choosing to live well, as best they can, even with a serious illness.

From its beginnings in pain and stress management, MBSR has expanded to other areas of healthcare, and beyond. It is now taught in hundreds of American hospitals, as well as workplaces, schools and prisons— even the US military are pouring money into mindfulness research, to help soldiers cope with combat trauma. Here, The National Institute For Clinical Excellence recommends the use of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people prone to recurrent depression, after studies showed it reduces the rate of relapse by 50 percent over 12 months.

All too aware that they often have little to offer their chronically-ill patients, GPs are on board. According to the Mental Health Foundation, which is running a campaign to promote the use of mindfulness for stress and depression, 68 percent of doctors think that their patients would benefit from learning mindfulness skills. Mindfulness has reached governmental ears too—the 2008 Foresight report on Mental Capital and Wellbeing recommended mindfulness (“taking notice”) as one of the five ways that anyone can look after their mental health.

So how does it work? For starters, mindfulness shows us that our search for happiness can actually make us less content. We work hard to keep our bodies in shape, be successful in our jobs, and maintain good relationships with family and friends, but by constantly striving to make things better, we often get more stressed. Mindfulness teaches us to pay attention to the present moment, rather than fretting about the past or future—observing thoughts, feelings and events with a gentle curiosity. As we develop our practice, we don’t get so caught up in the maelstrom of activity inside our heads and out in the world. We start to see that ‘thoughts are not facts’, and that we can relate differently to our minds—observing our negative thinking patterns with kindness.

One of the reasons mindfulness can be so effective for depression is that it helps people get some distance from their thoughts, rather than feeling overwhelmed with a constant churn of self-criticism. In our book, we describe the case of Dixon, who was referred to a mindfulness course by his GP. “Depression makes people focus on themselves and their problems to the point that they stop functioning,” he told us. “Mindfulness stops you from doing that – it stops you from allowing your mind to tie you up.” Dixon’s mindfulness training became even more relevant when he was later diagnosed with bone cancer—he says the “mental tools” he learned have helped him deal with the pain and worry of a life-threatening condition. “Meditation sets my mind up to crack on with life rather than sinking into a swamp of despondency.”

So, far from being a retreat from the world as it is sometimes characterised, meditation equips us to engage with the world more fully—even if we don’t have any major heath problems, couldn’t we all benefit from increased attention and emotional skills, improved relationships and reduced compulsive behaviours, all of which are proven effects of mindfulness practice? We all know that exercising our bodies is good for us—mindfulness is simply the mental equivalent.

The value of encouraging people to practise mindfulness could go beyond simple health benefits. If enough of us trained in doing less and noticing more, creating the beginnings of a more mindful culture, might we spare ourselves some of the suffering of boom and bust economic cycles, or the perils of runaway environmental destruction? Aren’t these collective manifestations of the same mindless habits that cause us so much stress on a personal level?

Mindfulness won’t instantly remove all our problems—it means letting go of the fantasy that there’s a quick fix for all our difficulties, and instead being willing to keep returning our minds to the present moment, even when that feels unpleasant. Practicing it takes effort, patience, and courage. But the rewards can be great—by developing the stillness to appreciate the wonder and richness of life as it is, we can discover well-being right where we are, rather than always desperately striving for future happiness, stuck in a whirlwind of counter-productive speed. So, maybe for a short while each day, don’t just do something, sit there.

Posted on The Mindful Manifesto

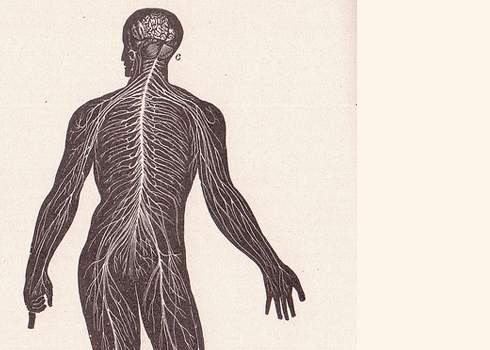

Illustration of the nervous system, from the book The Human Body and Health, revised by Alvin Davison, published in 1908 by Alvin Davison.