It’s there when I wake up. Something’s wrong. I haven’t opened my eyes yet. A minute ago I was sleeping. But now I’m awake and it’s there, lurking: Something’s wrong. My breathing tightens. I stretch my legs beneath the sheets. I feel my heart beating. The sense of creeping fear is diffuse, elusive, hard to pin down. It’s like catching sight of something from the corner of my eye. Something’s wrong.

Only nothing is wrong. I know that. I’ve experienced these bouts of dread for as long as I can remember. It’s familiar, which does not help me hate it any less.

Explaining chronic anxiety to someone who doesn’t experience it is like trying to describe a color they’ve never seen. I have friends who are surprised I suffer from anxiety. After a lifetime of learning to compensate, to push myself beyond my six-year-old fear of joining the Girl Scouts, I do not come across as a nervous Nellie. I am outgoing, talkative, adventurous. Last spring, I planned a Class IV whitewater rafting trip with my husband for three days in the summer. I started dreading it the minute after I booked it.

I go for long periods when anxiety leaves me alone, and I forget the tightness of its grip. But when it comes back, triggered by stress or worry about an upcoming challenge, it sticks around, greeting me every morning like some noxious troll who won’t shut up. Something’s wrong, it insists, or more accurately, something is about to go terribly wrong. I know this thought is irrational, but that doesn’t stop the spiral of anxiety that ensues. Nerves twitch under my skin. I scroll my list of things to do and feel uneasy, even about the tasks I’m (supposedly) looking forward to. When days begin like this, happiness is not on my agenda.

Too Much of a Good Thing

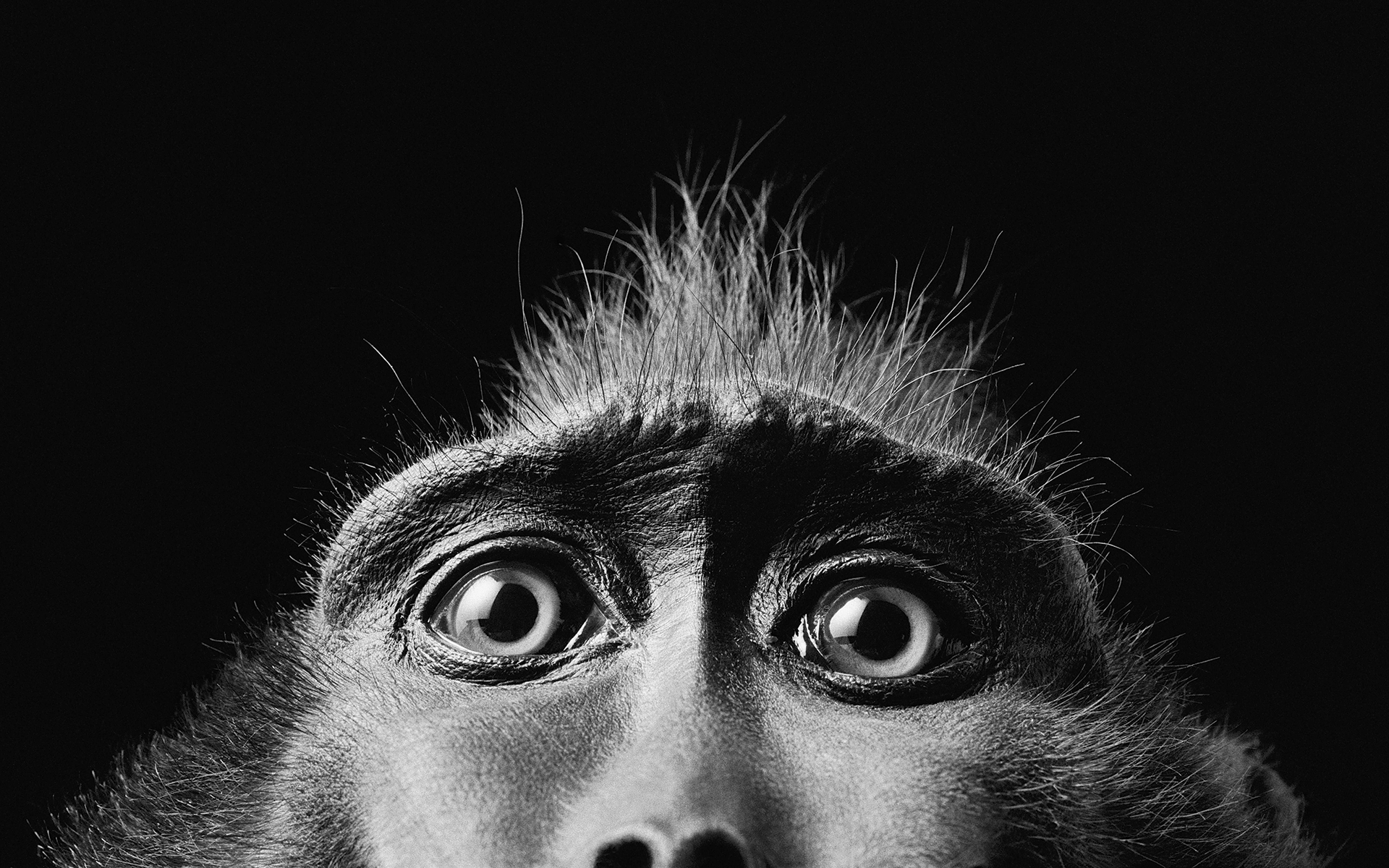

All animals react when confronted with danger, and that’s a good thing. The so-called fight-or-flight response, also known as the stress response, helps animals either move away from a threat or fend it off. Anxiety—the ability to anticipate danger—is even more of a good thing. Anxious humans who avoided areas rife with predators or saved food in anticipation of crop failure had a better chance of staying alive to pass on their genes. And make no mistake, that’s all evolution cares about. It doesn’t care that we exquisitely anxious humans might survive but be miserable a lot of the time, massaging our worry beads down to nubs. Let’s face it, in the modern world, with far fewer real threats in our environment, many of us are suffering from too much of a good thing.

Too much anxiety robs you of your capacity for joy. When everyday worry becomes chronic, it can flip over into one of several flavors of debilitating emotional disorders. Some sufferers develop specific phobias—agoraphobia, claustrophobia, social anxiety. Others, like me, suffer from generalized anxiety disorder, a free-floating emotional malady. The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that one in five Americans have had some kind of anxiety disorder in the past year. In turn, anxiety can lead to sleep disturbances, panic attacks, hypochondria, depression.

With so much misery at stake, it’s a relief to learn that lots of smart people have figured out how to ease anxiety. Whether you suffer from occasional worry or have a full-blown anxiety disorder, it’s possible to become fully engaged in life again. In the last three decades, scientists have decoded the spiral of reactions that, over time, build an anxious brain. Turns out, I’ve wired my own brain to be anxious. The good news is I’m learning to rewire it—and you can, too. The more we know about how anxiety actually works, the better we get at beating back the troll. Or at least making it behave.

Nothing to Fear But Fear Itself

To understand anxiety, you’ve got to start with fear, because anxiety is like fear run amok. Neuroscientists now know there are two distinct pathways in the brain that trigger the fight-or-flight response. Here’s the most direct one: You encounter something in your environment—a man running toward you with a knife, a car veering into your lane on the highway—and a part of your brain called the thalamus sends visual information directly to an almond-shaped structure called the amygdala. That’s the control center for the fight-or-flight response. When the amygdala detects a threat, it triggers a surge of adrenaline and an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and muscle tension—to prepare you to act. A few weeks ago, as I rode my bike home, I suddenly braked, turned my handles sharply to the left, and barely avoided being hit by a car that had run a stop sign. I never saw it coming. But my amygdala did, and it may have saved my life.

To understand anxiety, you’ve got to start with fear, because anxiety is like fear run amok.

Here’s the modern glitch in that evolutionarily brilliant response: “We don’t go into fight or flight just when we’re being chased by a bear,” says Adrienne Taren, a neuroscientist and emergency-room physician at the University of Oklahoma. “We’re getting it every time our email pings or we’re sitting in traffic. Our amygdala is just going and going and going.” That constant barrage of low-level alarm is what we call stress.

So where does anxiety come in? Because we’re such imaginative creatures, we can get stressed out by simply thinking about something that may go wrong. The part of the brain that worries about a future event we’re anticipating is the prefrontal cortex, and that’s where the second pathway to anxiety starts—the one that creates that flurry of anxious thoughts you can’t seem to control. Worried thoughts in the cortex trigger a stress response in the amygdala, which explains why we can freak out about things that aren’t even happening. “I think of the amygdala as sitting there watching cortex television,” says Catherine Pittman, a clinical psychologist and coauthor of Rewire Your Anxious Brain. “You can be on your back porch, looking at the beautiful trees, but you’re thinking, ‘How am I going to pay my mortgage with these medical bills? They’re going to take my house away!’ Your anxiety spikes even though nothing around you is dangerous.”

It’s important to realize that the cortex can’t create anxiety on its own. It can only activate the stress response when it gets the amygdala involved. The amygdala, on the other hand, can bypass the cortex, detect threats in the environment, and react, quickly. When I swerved to avoid being hit by that car, my amygdala took over while my cortex was still figuring out what was happening. Similarly, when a veteran feels anxious at what sounds like gunfire, it’s because his amygdala has gone into overdrive. The amygdala is constantly sweeping the scene, comparing our current experiences with associations learned long ago and some that are probably hard-wired. When it finds a match, it compels us to react, even if the current situation really isn’t all that threatening.

The cortex is like a parent who intervenes to prevent a child from acting on his or her impulses. It acts as a check for when the amygdala overreacts, recognizing, for instance, that what sounded like gunfire was actually a car backfiring and promptly tamping down the anxiety. Sometimes, though, the amygdala’s response is so overpowering that it drowns out the voice of the cortex. That’s anxiety in overdrive.

The neuroscientist whose work led to the realization that anxiety arises from two distinct neural pathways is Joseph LeDoux, the director of the Emotional Brain Institute at New York University. His discovery of a direct neural pathway to the amygdala overturned the conventional wisdom that the cortex played the starring role in creating anxiety and instead placed the amygdala at center stage. This revolutionary development has enormous implications for why some anxiety treatments work better than others—and for why mindfulness approaches are now getting so much attention.

Getting to the Amygdala of the Problem

In the 1960s, people who suffered from anxiety would have been advised, taking a cue from Freud, that they needed to uncover the unconscious forces driving their fears. By the ’70s a more pragmatic approach had taken hold: Learn to change the thoughts and behaviors that lead to anxiety. Cognitive therapy has proven successful in helping people interrogate the negative thoughts underpinning their worries: Are people really judging me so harshly when I give a presentation? And what’s the worst that can happen if they are? Patients learn to question whether their thoughts are realistic or if they’re catastrophizing based on scant evidence.

We now know that cognitive therapy is effective at tackling anxiety that originates from thoughts in the cortex. But it does nothing to tackle anxiety that arises from reactions in the amygdala itself. “Your thoughts can’t change the way the amygdala reacts through using logic or reasoning with it,” says Pittman, who is also a professor at Saint Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana. “The amygdala only learns through experience.”

So where does anxiety come in? Because we’re such imaginative creatures, we can get stressed out by simply thinking about something that may go wrong.

So how do you target the amygdala directly? One way is through behavioral, or exposure therapy, which helps the amygdala “unlearn” associations it’s made between danger and particular experiences—like encountering strangers, loud voices, boarding a plane, or driving a car. Behavioral therapy uses the gradual, repeated exposure to whatever’s causing anxiety as a way to help the amygdala learn a more neutral association between the experience and our reaction to it.

Another way to treat amygdala-based anxiety is to simply calm down that part of the brain. Medications are one option. Xanax and its other incarnations are members of a class of drugs known as benzodiazepines. “They basically put the amygdala to sleep,” says Pittman. And that works. But if your goal is to lessen anxiety over the long haul, taking benzodiazepines will impede your progress. “What is learning?” asks Pittman. “It’s neurons firing repeatedly so that new connections form. Neurons have to fire to rewire. So if you give someone a medicine that prevents neurons from firing, how is the amygdala going to learn?” Alternatively, the reason that another class of drugs—the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors known as SSRIs—have proven helpful for anxiety is that they appear to help neurons form new connections. “SSRI’s promote more communication between neurons,” says Pittman. “People start to be able to think outside the box a little.”

But drugs aren’t the only—or the best—way to calm down the amygdala. There’s also the so-called relaxation response. It’s the “rest and digest” antidote to “fight or flight.” Using MRIs, scientists can now see how, just as the amygdala revs up during stress, it calms down when people employ the deep breathing exercises that prompt the relaxation response.

And that’s part of the reason that mindfulness shows so much promise for treating anxiety. Sitting quietly and focusing on the breath activates the relaxation response. But mindfulness-based meditation combines relaxation with something more: a nonjudgmental attitude toward emotions that arise, an acceptance of whatever happens. What the new brain research suggests is that, by combining the relaxation response with a cultivation of paying attention to our thoughts, we can address both of the pathways that lead to anxiety at the same time.

How Mindfulness Changes the Brain

Adrienne Taren began studying mindfulness because she was interested in stress. Studies have shown that mindfulness makes people less reactive to stress and better at regulating their emotions. But as a researcher at Carnegie Mellon back in 2012, Taren wanted to know what was happening in their brains. Her first study compared a group of people—not meditators—who exhibited mindfulness as a personality trait with another group with high stress levels. The results were striking. People who scored highly for mindfulness had smaller amygdalas than those who reported high stress. “The assumption is that a larger amygdala is more active,” she says. “If you have a smaller amygdala,you aren’t so stress reactive.”

The next question: Can people who aren’t mindful by disposition rewire their brains to become less reactive to stress? Taren enrolled high-stress, unemployed people in a three-day retreat, where half were taught relaxation strategies. The others were trained in a condensed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program. “We wanted to find out if there’s something specific about mindfulness that’s causing these effects,” says Taren, “not just that stressed-out people relaxed and felt better.” Taren measured the amygdala size of both groups, and after just three days of mindfulness training, the meditation group had smaller amygdalas. That suggested they’d actually made their brains more resistant to stress.

Perhaps even more significant, Taren found that the mindfulness training had weakened the connection between the amygdala and an area called the anterior cingulate cortex, a frontal region responsible for executive functions like decision making and paying attention. Decoupling the stress center from the logic center allowed people to feel more distance from their anxiety, which made it more manageable. “You’re able to just observe those emotions, which dampens the stress response that keeps the front of the brain from working,” she says.

Taren’s work echoes a growing body of research from neuroscience labs across the country suggesting that mindfulness causes brain changes in both the amygdala and the cortex. Neuroscientists are the first to say that they don’t completely understand the significance of these changes. But for now, they do know that breath-focused meditation seems to help people’s amygdalas become less reactive to their own self-critical beliefs. It also makes them less likely to see social encounters as threatening. When people with generalized anxiety disorder are shown pictures of emotional faces—happy, angry, or neutral—their amygdalas react to the neutral faces more fearfully than to the angry ones. “They perceive them as threatening because they don’t know what the person is thinking,” says Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist at Harvard University. “So they go on high alert.” Lazar found that, after mindfulness training, their amygdalas became less dense—the neurons were like trees that had been pruned—and no longer reacted to neutral faces as threatening.

Mindfulness training also changes the way the prefrontal cortex responds to anxiety. “Anxious people have that voice in their head 24/7, going: ‘What if? What if? What if?’” says Lazar. “Normally we completely identify with that voice, but mindfulness helps us step back and change our relationship to it.” Mindfulness works differently from cognitive therapy, which aims to change thought patterns to short-circuit worry. Instead of trying to eradicate anxiety, mindfulness gets you outside of it so it’s just an experience you’re having. That distance helps you endure experiences you find stressful or scary so your amygdala can learn a new way to react.

Adrienne Taren became interested in mindfulness from the perspective of a stress researcher. But when she saw the changes it evoked in the brain, she began a practice of her own. “I’m the Type A kind of overachiever who developed an anxious personality,” she says.

Mindfulness has helped her in the emergency room, where she needs to stay in the moment and make good decisions. It also helped after a painful bike accident. Taren is an off-road cyclist who rides on gravel for hundreds of miles, for fun. After healing from her extensive injury, she panicked when she tried to mount the bike for a competition. Her natural reaction was to suppress her anxiety. But her mindfulness training helped her see another way. “I started talking to my anxiety. I was like, ‘Hello, we’re going to be together for the next 20 miles.’ I was able to picture my anxiety as this little bubble of emotion floating along beside me,” she says. “It was almost comforting.”

A Little Fear Goes A Long Way

Around the same time my fear of joining the Girl Scouts was keeping me up at night, a little girl was born in a Midwestern town with a rare genetic disease. By the time she reached adulthood, the disease had entered her brain, destroying her amygdala. That woman, now known as Patient S.M., helped scientists discover the key role the amygdala plays in anxiety and fear. S.M. feels no fear from external threats.

To me, that sounded like a dream come true. When I first developed a mindfulness practice, I secretly hoped I could shrink my almond-shaped amygdala down to a peanut. To live fearlessly, able to take risks, pursue adventures, connect with other people without holding back out of worry that my body’s nervous system might betray my uncertainties? Sign me up.

But over the last year or so, my goal has shifted. Extinguishing anxiety is no longer what I’m after. Instead, when anxiety arises, I simply pay attention to its physical manifestations, and slowly—not because I’m wishing it away—my worry recedes. It sounds crazy, but having started on this journey to do everything I could to obliterate anxiety, I’ve learned to value the role it plays in my life. It helps me be more compassionate with myself. It reminds me to trust other people. And that leads us back to Patient S.M.

She has no fear, so her curiosity knows no bounds. She is aggressively social and wants to interact with every stranger she meets. “She has zero personal space,” says Justin Feinstein, a neuroscientist at Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, who’s studied her extensively. “There’s no bubble. She has no discomfort looking you in the eye even if you’re a total stranger.” When Feinstein took S.M. to an exotic pet store, she held a snake and closely examined it, rubbing its scales and stroking its flicking tongue. She wanted to touch a large dangerous snake—asking to do so 15 times—despite being told it might bite her.

S.M.’s story offers a lesson in the crucial balancing act between letting our curiosity lead us to new encounters and heeding the fear that makes us avoid them. She’s been the victim of assault many times—had a knife held to her throat, been held at gunpoint—because she is unable to recognize threatening situations. To be sure, living without an amygdala is dangerous. But for those of us with the opposite problem, whose amygdalas see threats all around us? We might benefit from paying more attention to our curiosity, the antithesis of fear.

In the weeks before our rafting trip, my greatest anxiety was of fear itself. I worried what I’d do if my body betrayed me, gasping for breath and panicking. I’d prepared for months, with daily meditation, but even so, my anxiety as we drove to the meet-up point was high. I used every tool in my box: I sang songs on the radio to distract me. I awoke at our campsite by the river the next morning and meditated. Then I took a half tablet of Xanax.

That first day on the river, I bonded with the four Hawaiian men in our boat. As we crashed over the rapids, I observed “me” in the boat, too busy to feel anxious as we paddled like crazy. My vantage point had shifted: Instead of feeling buffeted by each rapid, I just saw myself paddling down the river. I didn’t once panic…even on one particularly gnarly rapid when we crashed into a boulder and my husband somersaulted out of the boat. He was OK. And—I realized—I was too. For the next two days I meditated in the morning, but I didn’t reach for the Xanax. My amygdala was learning there was nothing to fear. My sensations of anxiety had changed to excitement. By the last day, I felt like I could paddle on whitewater every day.

I won’t lie: I’ve awoken anxious many days since that trip. But there’s a distance to my angst that wasn’t there before. I’ve noticed that the physical experience of anxiety doesn’t have to spiral out of control, that it can even make me feel more alive. I call this the Anxiety Paradox: By allowing myself to feel anxious, to not succumb to the desire to “just make it go away,” anxiety somehow lessens its grip on my psyche. And that opens up a space to let joy in.