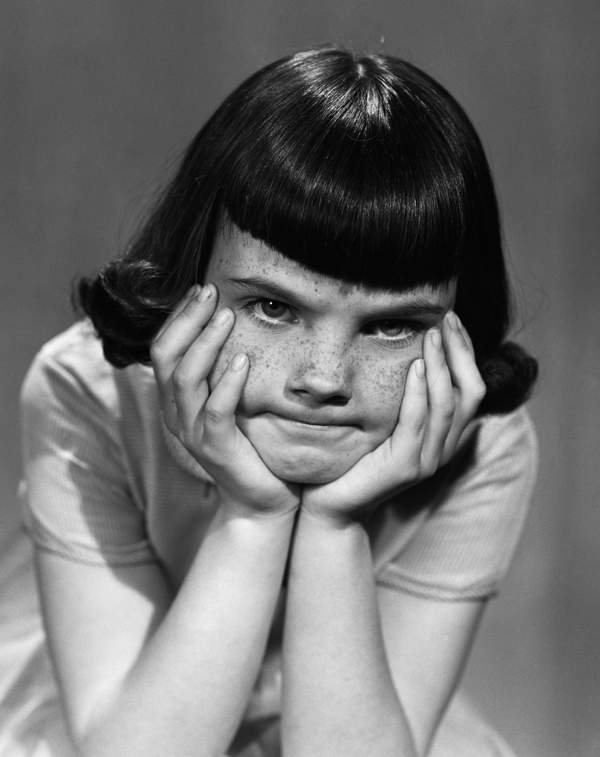

During long road trips when I was a kid, instead of switching on the radio my father sang, sometimes accompanied my mother. My brother had left home, so it was just me in the back, behind a blanket strung from door to door, pretending I was on a pirate ship headed for China, doing my best to blot out my father’s off-key warbling. Bernie was not a happy man, but his repertoire had a single theme: Happy Days Are Here Again, Smile (though your heart is breaking) and Put On A Happy Face topped his hit parade.

My mother wasn’t any happier than my father, but it was as if she had drunk the same cultural Kool-Aid as he. They both had got the message that happiness is the only worthy emotion. The rest—anger, disappointment, fear, sorrow—were signs of a weak character. Shameful. I got the message, too. Like so many Westerners, especially Americans, we believed we were supposed to be happy all the time—as far as I can tell, the number one, surefire predictor of misery.

“We have this default assumption that happiness is a calculus of pleasure and pain, and if you get rid of pain and multiply pleasures then you’ll be happy, but it doesn’t work that way,” says Darrin McMahon, a history professor at Dartmouth College and author of Happiness: A History. What’s more, he explains, “The idea of happiness as our natural state is a peculiarly modern condition that puts a tremendous onus on people. We blame ourselves and feel guilty and deficient when we’re not happy.”

As it turns out, the notion that we should be able to manifest our own individual happiness is a relatively recent concept in human history, starting in the late 17th century and continuing to develop during the 18th (see under: Thomas Jefferson and John Locke). Before then, suffering was considered the norm and happiness was thought to be a matter of luck. In fact, hap is both the Old Norse and Old English root of happiness—and it means luck or chance.

“The belief in our own happiness has been a progressive and liberating notion, yet it has a shadow side,” McMahon tells me. To me it seems as if our whole culture has been living in this shadow zone for some time: Don’t worry, be happy. Or, as with my parents, pretend to be happy, even when you’re not.

Are we desperately seeking happiness because we’re more miserable than ever before, despite the many perks of modern life?

So what are we really talking about when we talk about happiness?

Clearly, given the recent explosion of bestsellers, smartphone apps, websites, workshops, TED talks, online courses, magazine articles, and a slew of research programs dedicated to helping people become happier, it’s no idle question.

Yet, I wonder: Are we desperately seeking happiness more than ever before because we’re more miserable than ever before, despite the obvious perks and advantages of contemporary life? Or are there important lessons to be gleaned from the thriving happiness zeitgeist that can actually make us, well, happier, in a real and authentic sort of way? Both explanations, it would seem, are true.

“Most of us have signed on for a cultural approach that has to do with possessions and status and achievements as markers of happiness,” says Emiliana Simon-Thomas, science director of the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, which offers a free 10-week online course called The Science of Happiness. “But having bought into that vision and aspired to it on a fundamental level, we’re lonelier than ever,” she explains, noting that an estimated one out of every three people has no one in their life they can really talk to. “We’re more disconnected from our communities and less able to cooperate and we’re anxious about potential failure. All of these factors make happiness much harder to evaluate.”

Still, perhaps the tsunami of interest in happiness reflects a cultural awakening and swing away from the unsatisfying vision that has dogged us since long before my father started crooning Happy Days Are Here Again. There seems to be a growing hunger for a truer, more achievable and sustainable happiness than our shopworn trifecta of stuff, status, and achievements. The 114,000 people who signed up for Greater Good’s online course would seem to suggest as much. So would the 120 participants who flocked from around the globe to the Esalen Institute to attend Greater Good’s “Science of Happiness” weekend.

What better setting for a happiness weekend than the birthplace of the human potential movement, I think, as I enter the large, lodge-like dining room that, along with the famous cliffside mineral baths, is the heart of the Esalen experience. A loud buzz reverberates as guests help themselves to the evening meal of shepherd’s pie, then find a place at one of the long tables. Some have come on their own, others with a friend or partner, but everyone seems curious about who else is there and why—and seemingly random seating arrangements result in connections that last all weekend and perhaps beyond. Many of the folks I talk to have already taken the online course and want to go deeper. Others, including therapists, teachers, doctors, environmentalists, and leadership consultants, plan to bring the lessons back to their communities and families. And just about everyone aspires to boost his or her own happiness quotient. Laurie, destined to become my weekend BFF, tells me she believes opening to happiness is a lot like exercise. “You have to set the intention, then work your muscles by trying out various practices, but without worrying too much about how happy you are at any one moment,” she suggests. And even though we’re at Esalen, with its countercultural mystique, the crowd doesn’t seem to be in search of a woo woo experience. One woman, who could be speaking for the majority, tells me, “I like that the material isn’t all touchy-feely. It’s about changing your habits and your brain. And it’s based on real science.”

The 40% Solution

So what is this science of happiness, anyhow?

To me, one of the most interesting findings is the now well-documented fact that we humans are notoriously lousy at predicting what will—and will not—make us happy. “People think things that are unpleasant are going to be crushing for a much longer time than they are,” Simon-Thomas tells me a few days before the workshop, which she is co-leading. “They also think that pleasures, such as a new material possession or an incredibly empowering achievement, are going to lead to long-term boosts to their well-being. But what the studies show is that we get over and habituate to the things that are frightening or harmful or sad, and at the same time, we habituate to wonderful things.” In other words, our lowest lows and highest highs don’t last. “Pleasure is really important, but you can’t put it at the top of the list of aspirations.”

Not only that, it turns out that the more zealously we pursue our notion of ideal happiness or hold ourselves to impossibly high standards, the more likely our efforts will backfire. “Not having exceedingly high expectations is a key to actually obtaining some measure of happiness,” says Iris Mauss, an associate professor of psychology at UC Berkeley who studies the paradoxical effects of pursuing positive emotion.

When I consider my own life, this seems ridiculously, painfully obvious. How often was I convinced to my core that the next boyfriend, the move to a different city, the great magazine assignment or Off-Broadway production of one of my plays would finally, once and for all, make me permanently happy? Hell, even the next hot fudge sundae had the potential to turn my life-is-scary-and-then-you-die personality into something cheery and light, at least temporarily. I may not have counted on winning the lottery, but my belief in future salvation turns out to have been just as fantastical.

It turns out that the more zealously we pursue happiness or hold ourselves to impossibly high standards, the more likely our efforts will backfire.

Happy. The word alone, with its simplistic connotation of pleasure, gets us into big trouble. That’s why some researchers, such as University of Illinois happiness pioneer and psychology professor Ed Diener, have dropped the word altogether. Diener prefers “subjective well-being” as a more accurate way to describe an individual’s degree of life satisfaction. Martin Seligman, the godfather of Positive Psychology and author, most recently, of Flourish, has also shifted his focus from happiness to well-being, which he deconstructs into five essential elements: positive emotion, engagement in life, meaning, positive relationships, and accomplishment. Other psychologists have teased happiness into two components: eudaimonic happiness, the well-being that arises from a sense of purpose or service to others; and hedonic happiness, which comes from enjoying a good meal, making love, or other passing pleasures. And though both types of happiness are essential to a balanced, contented life, a recent study conducted by Barbara Frederickson at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Steven Cole of the UCLA School of Medicine found that blood samples of people with high levels of eudaimonic happiness demonstrated a better immune response profile than those with high levels of hedonic happiness.

Regardless of how we define it—eudaimonia or hedonia, well-being or subjective well-being—it’s striking to discover that after correcting for our genetic inheritance and life circumstances, we’re each left with the capacity to control about 40% of our individual happiness. I find this number amazing. Who knew that happiness is an equal opportunity emotion, as available to grouches and worriers as it is to the innately cheerful? This is definitely good news for anxious types like me.

The DIY Path to Joy

The key is intention, says Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside, and author of The How of Happiness. “I’m not suggesting we all try to become happier,” she tells me. “But those who feel their lives are not quite flourishing or who experience a lot of negative emotions can benefit from positive interventions.”

Although Lyubomirsky suggests multiple strategies for boosting happiness, she cautions that there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. “Many of us persist in searching for the one true path to happiness, like the one diet that will work when all others have failed,” she says. “In truth there is no magic bullet. There are hundreds of things you can do. You have to experiment and choose what’s right for you.” Hearing this comes as a relief; I’m always suspicious of books and articles that evangelize the one true way.

Among the many strategies that Lyubomirsky discusses are: conveying your gratitude to others either verbally or in a letter; cultivating optimism; practicing deliberate acts of kindness; nurturing strong social relationships; forgiving those who may have hurt you; genuinely savoring life’s joys; participating in activities that truly engage you; practicing mindfulness; and taking care of your body, including exercising and cultivating laughter.

“Start with small steps to create an upward spiral,” advises Lyubomirsky. “Sense which of these activities feels most natural and most easily fits with your lifestyle, then try something a little more challenging later on. Ideally, some of the practices, such as focusing on relationships and becoming a better listener, will in time become automatic. Others may require ongoing intention and effort, like remembering to take a dose of a helpful medicine.”

Practicing gratitude, in particular, may feel artificial, but study after study has shown it to be one of the most powerful activities we can engage in. Lyubomirsky says, “Gratitude is a great way to consider what’s good about your life, instead of focusing on what’s not good or what other people have that you don’t. Lots of people say it’s hokey to count your blessings, and I’m actually one of them, but the payoff is tremendous.”

Change Your Brain

The cynics, skeptics, and curmudgeons tempted to dismiss gratitude and other happiness-boosting practices as New Age hokum would be well advised to consider the mounting evidence linking positive emotions to markers for good health. Our brains tell a significant part of the story.

“Research suggests that when people consciously practice gratitude, they’re increasing the flow of beneficial neurochemicals in the brain,” Rick Hanson, a neuropsychologist and author, most recently of Hardwiring Happiness, tells me over hot and sour soup in San Rafael, California. “What passes through the mind resculpts the neural structure of the brain. If we focus on what we resent or regret, we build out the neural substrates of those thoughts and feelings. But if we rest our attention on things we’re grateful for, we build up very different neural substrates. New blood starts flowing. Existing synapses become more sensitive and new synapses grow.”

Who knew that happiness is an equal opportunity emotion, as available to grouches and worriers as it is to the innately cheerful?

The key, Hanson adds, is promoting sustained attention. Just having positive experiences isn’t enough. In order for those experiences to have a real impact on our brain, we need to stay with them for longer periods than may be our custom. Hanson calls this taking in the good.

The practice goes something like this: Notice something pleasant already present in the foreground or background of your awareness, such as a physical pleasure, the sight of a beautiful tree, or a feeling of closeness with someone. Stay with it for five to 10 seconds or longer. Open to the feelings it produces in your mind and body, enjoy them, and gently encourage the experience to intensify. Finally, imagine the good sinking into you as you sink into it. You might even visualize the experience as a soothing balm or a jewel in your heart—a resource inside yourself that you can take with you wherever you go.

This sounds and feels good; I’ve even tried it during my daily walks through the hills in my neighborhood, and I like it. I’ve savored the beauty around me and felt it soak into my body. Still, I can’t help wondering about my default anxious self. How does “taking in the good” affect the old wiring and issues related to fear and safety? These issues, Hanson says, tend to be rooted in the more primitive parts of the brain—the subcortex and brain stem—areas that are more resistant to change than the left prefrontal cortex, which is associated with positive emotions and greater neuroplasticity.

“It’s important to distinguish between real threats and false alarms,” suggests Hanson. “Trust yourself to be aware of real threats, and you’ll be more comfortable dismissing the false alarms. You need to recognize at the cognitive level and in the body that false alarms are delusional. Learn to calm your body and build up inner strengths, such as mindfulness, gratitude, and compassion.” Because our brains can only process a limited amount of information at any one time, he says, the more we focus on positive experiences, the less room there is for the negative to take hold.

Still, I’m slightly wary. Is all this emphasis on the positive like trying to put a giant Band-Aid over what is sad and painful and difficult in our lives?

“I don’t believe in positive thinking. I believe in realistic thinking,” says Hanson, who also teaches mindfulness meditation. “It’s important to see the whole mosaic of reality. The good tiles in the mosaic are the basis for growing resources inside myself to help deal with the bad tiles.” The exercises, then, aren’t about suppressing or re-envisioning the negative; rather, they’re about strengthening other modes of thinking and feeling. So: Be upset when you’re upset, sad when you’re sad, angry when you’re angry. At the same time, intentionally cultivate inner resources that will not just help you cope, but will allow you to become more content with your life, regardless of changing circumstances.

As if to underscore the point, during the course of my research for this story, I come across a paper titled “Emodiversity and the Emotional Ecosystem,” whose lead authors are Jordi Quoidbach and June Gruber. Basically, using the biodiversity of ecosystems in the natural world as a model, they found in studies of more than 37,000 people the first evidence for the notion that emodiversity—the variety and abundance of emotions that we humans experience—might play a unique role in our well-being. The authors write, “A wide variety of emotions might be a sign of a self-aware and authentic life; such emotional self-awareness and authenticity have been repeatedly linked to health and well-being.”

When our small, separate self loosens and we dissolve into what’s around us, that’s awe, the ultimate happiness strategy.

Not only does this finding make sense, it’s also the perfect corrective to the damaging cultural myth that plagued my parents and continues to cast a shadow over the lives of so many—namely, that we should be happy and experience pleasure most of the time, otherwise there’s something innately wrong with us.

There is real happiness, to be sure. It just doesn’t look the way most of us have been conditioned to think, which is precisely what sages have been telling us for millenia. Epictetus put it this way: “Do not seek to have events happen as you want them to, but instead want them to happen as they do happen, and your life will go well.”

The Promise of Awe

On Saturday evening at Esalen during The Science of Happiness weekend, clusters of participants gather on the wide stretch of lawn to take in the blazing sunset that streaks across the sky. The fiery globe has just dipped into the Pacific, a sweet sight after a day of rain. There is silence all around as we feast our eyes on the technicolor sunset, the vastness of the ocean, the rocky cliffs that extend up and down the coast as far as the eye can see. And though this scene could not possibly have been programmed by the workshop’s leaders—nature doesn’t allow such planning—it’s the perfect lead-in to the evening’s talk on awe.

“Awe uniquely predicts happiness,” says Dacher Keltner, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley and the faculty liaison to the Greater Good team. I am blown away by this news. After all, who doesn’t treasure experiences such as tonight’s sunset, in which our sense of being a small, separate self loosens and even temporarily dissolves into the mystery and grandeur of the moment?

Keltner is unreservedly enthusiastic as he describes the latest research on awe, which appears to give a major boost to the body’s immune system. A recent study conducted at UC Berkeley that Keltner coauthored found that the experience of awe has been linked to lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, proteins that signal the immune system to work harder. And though cytokines play a key role in fighting infections, sustained high levels of these proteins are associated with disorders such as type 2 diabetes, heart disease, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and clinical depression.

“The fact that awe promotes healthier levels of cytokines suggests anything we can do to foster it—a walk in nature or listening to great music or spending time around people who inspire us—has a direct effect upon our health and life expectancy,” Keltner explains. “In the big sweepstakes of what makes us the most happy, awe may be the champion.”

On that upbeat note, the program ends. I’m not at all surprised when, not long after, many of us head straight to the mineral baths—to soak in the warm waters and gaze at the glittering curtain of stars flung across the night sky.