One afternoon in May, sitting on the floor in a small, private room at Fort Worthington Elementary/Middle School in Baltimore’s Clifton-Berea—one of the poorest urban neighborhoods in America—Kamaya, ten years old, in fifth grade, and Jahlil, ten, also in fifth grade, are talking about something new. It’s the role of mindfulness in their lives.

Kamaya’s father is in prison (“I don’t have my dad right now—he’ll be home next year”) and her mother has her own house; Kamaya lives with her grandmother. A natural chatterbox, Kamaya quickly mentions uncles and cousins and a great-grandmother, a big extended family. She says she got mad just last night, because she wanted to play with her friends, and her mother, who visits her sometimes, wanted her to go to sleep. But instead of fussing and yelling and waking her grandmother, who wasn’t feeling well, Kamaya “took a stress breath,” which calmed her down. She didn’t wake her grandmother. And then she went to sleep herself.

Jahlil is a different sort of child—so quiet you might worry about what he’s thinking or feeling. He lives with his mom, and has a three-year-old sister; a younger brother died in childbirth. Jahlil gets to see his dad, who takes him shopping for clothes and to his favorite sort of movies: “Scary movies.” He doesn’t like school: “It’s boring. My science teacher, I don’t know about him.” The teacher gets very upset with him, he says, “Because my friends, and me, do bad things.”

When he’s hard on you, what do you do? I ask Jahlil.

“I say in my mind, ‘He should be fired.’ And then I go to the corner and breathe.”

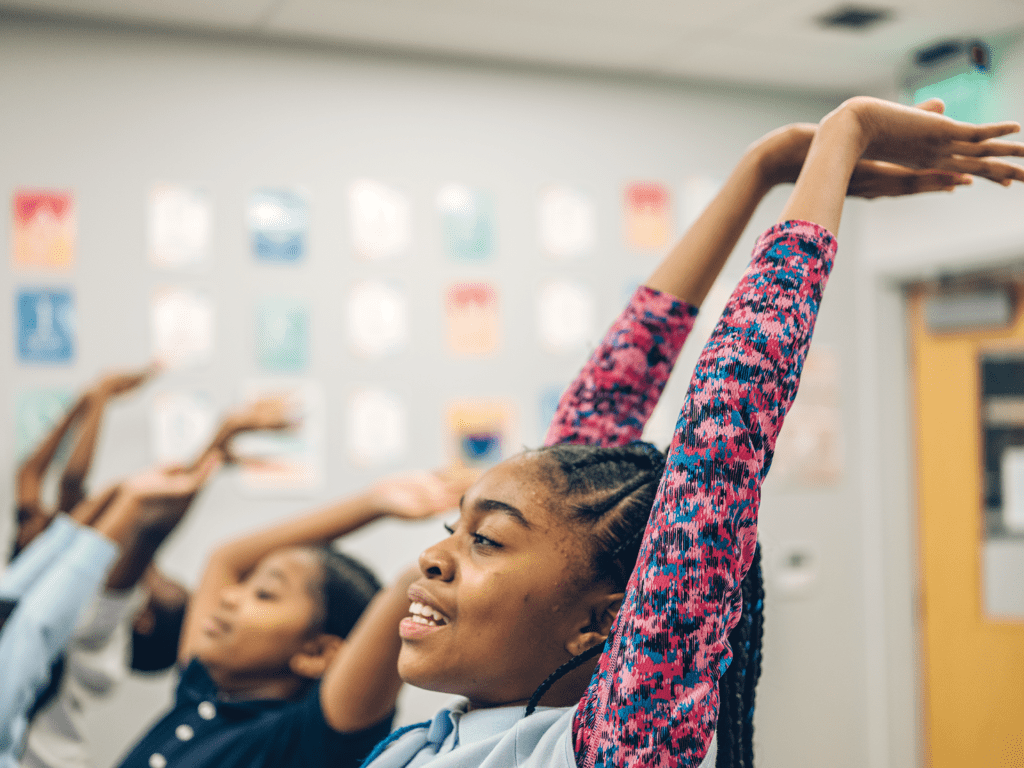

Jahlil and Kamaya are using the techniques of clearing their minds, of concentrating on their breath, being taught at Fort Worthington by Holistic Life Foundation, a local nonprofit started by three neighborhood guys almost two decades ago; it uses mindfulness and yoga to help students cope with the stress and difficulty of their lives, which can be extreme.

In Clifton-Berea, children grow up fast and often have to deal with the traumas of poverty, violence, and drug abuse. Last year, the Baltimore Sun wrote that the neighborhood embodies the convergence of “all things bad,” starting with a life expectancy four years less than the city’s average, the lowest in the state. “Students hear gunshots during the night and come in crying,” Principal Monique Debi says; in the past two weeks, there have been six shootings and four murders in the immediate vicinity. “I took that Sun article and showed it to my staff: ‘What are we going to do to change things for our babies?’”

Mindful Moment is the go-to program. It’s designed to help students stop, to find calm and control when a conflict threatens to overcome them emotionally.

The answer is to get creative, to find new tools for students.

HLF is all about empowering children—even young children. Mindful Moment is the go-to program. It’s designed to help students stop, to find calm and control when a conflict threatens to overcome them emotionally.

Jahlil recently went into a bedroom at home when his uncle flew into a rage and started cursing him because his video game had been interrupted. “I went downstairs and took a breath,” Jahlil says. “And then I just go back to my room, and he come and say he’s sorry, and started being nice to me.”

So maybe you were able to teach your uncle something?

“Uh huh,” Jahlil says, quietly, seemingly unimpressed. “That’s what happened.”

The challenge is huge and, as HLF sees it, so are the possibilities, for what their program might do. When I take a tour with the three founders of HLF through the West Baltimore neighborhood where two of them → grew up, I see heroin addicts sway and lean on various corners: “The kids in our program, that might be their mom there, nodding outside that liquor store,” says Atman Smith, one of the founders. “And until they find their inner light and inner peace and realize they can rise above any condition, they might not have the means for appreciating their worth.”

This is, you might say, the ultimate attempt at a solution from within: Some neighborhood guys who went off to college nearly 25 years ago but came back, to solve the challenges for their city’s children by helping them forge the mental tools to cope.

HLF is pursuing the power of self-possession, one child at a time—they now touch some 4,500 children a week in Baltimore, with Johns Hopkins and Penn State having studied the effects of its programs—and it does make one wonder what the possibilities are, and something else, as well: Just who are these guys?

Hippies of the Hood

Baltimore neighborhoods are filled with cheek-by-jowl rowhomes and back alleys, places of intimacy and, often, trouble. Ali and Atman Smith, two of the three founders and guiding lights of HLF, grew up on North Smallwood Street, in West Baltimore. It’s a place they still know well, as they take me back to give a tour.

“You ain’t sent me your information,” Atman, who seems in equal measures sweet and straightforward, calls out of Ali’s SUV to Todd, a guy on the sidewalk in his late teens.

“Look at how big he’s gotten, goodness gracious,” Andrés González says. Andrés grew up 15 miles south of Baltimore and met Ali and Atman at the University of Maryland; he came to Smallwood to live with Ali after college in ’01, with Atman moving to a house down the street in ’02, until all three moved to different sections of the city a few years ago.

“He’s doing a thing on music,” Atman says to Andrés. “I recommend you’all be friends on Instagram.”

“I got a little mini studio at the crib,” Andrés, a hip-hop enthusiast, calls out to Todd. “If you want to come through and lay some stuff, I got you for sure, man. That would be awesome.”

“Be safe out here, Todd,” Atman tells him, and then we move on, heading south.

They point out touchstones: Where Atman’s godmother worked in a doctor’s office next to a church, a missing house that’s become a park, Everyone’s Place bookstore. There’s famous Pennsylvania Avenue, where Black musicians and singers—Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, and James Brown, among many others—would come to perform, though nobody’s headlining there any longer.

When we hit West North Avenue, Andrés points out, “The riots over Freddie Gray [the city erupted after Gray died in police custody in 2015], they came down this road. This corner store got hit, they burned a liquor store and a beauty shop.”

“None of the Black businesses were touched,” Ali says.

I ask Ali if the neighborhood is worse off than when he and Atman were kids, in the ’80s. “You can look around and see, most of the houses are boarded up and dilapidated,” Ali says in his direct style, making the obvious even more obvious. “There were more homeowners when we were here. A lot of homeowners moved away, a transient rental population took over.”

The feeling, midday on a hot afternoon, is not one of danger so much as abandonment, as if something came storming in and a place was left behind. That something is an egregious, on-going lack of opportunity. It’s a place in slow motion.

Atman was the last of the three to move out of the neighborhood, to Charles Village, in 2017, and by then heroin dealers were hanging out on his front stoop on Smallwood. If he asked politely, they would cross the street and sell from there.

HLF’s founders don’t shy away from any of their old haunt’s troubles, but it’s a mistake to miss how, back in the ’80s when they were kids, this was their world too.

HLF’s founders don’t shy away from any of their old haunt’s troubles, but it’s a mistake to miss how, back in the ’80s when they were kids, this was their world too, a story that Ali tells:

“The family across the alley from us was just as much family as my mom and dad and brother. Their mom, Bo, was my mom’s best friend. She was the old medicine lady of the neighborhood, a doula before doulas were a thing.

“It was warm and connected, like one big household with the street as our shared living room. Raising children, listening to ballgames, wrestling on the front porch, running through the streets… It was all done together in the open. That was normal West Baltimore neighborhood life.”

Also normal, from the time Ali and Atman were small boys, was yoga. Their father Smitty, a high-school basketball coach, was a practitioner—well, maybe it wasn’t so normal, since Atman nicknamed them “hood hippies”—and Smitty had his boys on the mats striking poses before school. They attended Friends School of Baltimore in upper middle-class Roland Park—this was their mother Cassie’s idea, to get them a better education and broaden their horizons by rubbing shoulders with all different sorts of kids. (Ali sends his two young sons to Friends School of Baltimore now.)

“Although we were eating vegetarian and practicing yoga and meditation,” Ali remembers, “we also just had a regular life like everyone else. There was a Black-owned corner store where we would be sent on errands and buy penny candy. We spent a lot of time there, including whenever there was a blackout, because he had a generator. We watched movies there on his satellite TV, since there wasn’t any cable in the neighborhood, and it was also just a lot of fun to watch movies in a big group. What we learned from our parents about yoga and meditation in those early days on Smallwood remained imprinted on our minds, and someday we would return to it.” →

Ali, Atman, and their new friend Andrés would become inseparable at the University of Maryland, and came back to Baltimore together two decades ago. They wanted to create a business that would change the world. They had no idea what that might be.

Smitty gave them use of the house on Smallwood, rent-free. They began working seriously with Uncle Will (he wasn’t actually their uncle, but their father’s original yoga teacher and best friend) going to a park pre-dawn at nearby Lake Montebello to meditate. Smitty grew impatient. “At times,” he says, “I would call, and it got to the point where they didn’t want to answer the phone, because I would tell them, You say you’re doing this, you say you’re doing that. You’re not doing a thing. Show me something.”

They were doing something: working hard on themselves, though it was hard to measure. Something had shifted, though.

“I think it was people asking us,” Ali says, “about our calm and peace and happiness. They’d say, ‘You have no business being happy if you’re broke and living around Smallwood Street. Something ain’t right.’

“That’s when we realized something Uncle Will taught us. We couldn’t just sit on the practice—we had to teach it to others.” But…how?

Cassie was working at nearby Windsor Hills Elementary School (she was a longtime social-services →worker at various schools) and an idea popped up: Why not coach football to some of the more difficult kids? The boys thought about it over a weekend, and a different idea emerged: Not coaching, but an after-school yoga program, a leap of faith in the power of the path they were going down. That was the beginning.

Ali, Atman, and Andrés had never worked with children, or run a program. They didn’t know enough to have the kids fill out permission slips. It sounds almost scary now: The principal gave them 20 of the worst- behaving kids, space in the school basement, and carte blanche to figure out what to do with them. “They were happy to get free after-school care,” Andrés remembers, laughing. “As long as none of them were missing any arms when we returned them.”

Initially, they drew the students in by promising time spent outside, or in the gym, or field trips, and then started introducing yoga. The results were quick: “We would go from picking up half of them from detention,” Ali says, “to picking up a quarter from detention, to none of them. We started by breaking up several fights a day, to not any fights, to parents and the principal and teachers saying, ‘We don’t know what you all are doing, but keep doing it, because it’s working.’”

Out of those first 20 kids, back in 2001, all are doing well now, Ali says. “None of them are locked up—they’re all working, or have kids, or they’re doing something productive with their lives.”

Yoga and mindfulness are powerful tools, they believe. But part of their effect was, certainly, their way of being. Andrés tells a story: Early on, he and Atman had to shut down the after-school program for a few days to segue off for their own training—the children didn’t see them for almost a week. When Andrés and Atman returned, the kids already knew why they’d been gone: You’ve been locked up! The kids were sure of it. Andrés and Atman have been in jail.

Which wasn’t true, but that was the only explanation these children had, for two reasons: They knew that Andrés and Atman would abandon them only if something dire had happened, and the only dire thing they could come up with, in the world they were trying to grow up in, was what they’d seen happen to trusted adults again and again: You must have been locked up.

Ali and Atman and Andrés kept showing up. And now they knew they were on to something.

Growing Beyond Baltimore

Today, HLF’s core programs include yoga and mindfulness classes at 16 Baltimore city public schools, and another 20 in schools across the county; the foundation works with some 4,500 students a week and has 38 employees, with a yearly budget of $2.1 million.

At this point, HLF’s track record and level of knowledge and experience in the field of meditation/mindfulness/yoga for urban youth is among the strongest in the nation. HLF staff are frequent presenters at national and international conferences and workshops, and HLF teachers have presented programs for people at all ages and stages all over the United States and Canada, in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

Which is not to say the organization went from zero to 60 just like that. Over the years, funding has been a major problem, to the point where they wondered if they’d have to leave Baltimore; for the better part of a decade, Ali and Atman and Andrés didn’t pay themselves, surviving on odd jobs and the continuing largesse of Cassie and Smitty. Andrés laughs about their organizational naiveté. But once they finally gave in to the idea of specific roles—Andrés is now marketing director—so that all three of them weren’t responding to the same emails, HLF’s footprint got bigger fast.

Still, the challenges are fundamental: Back at Fort Worthington Elementary, I watch a girl, perhaps ten, slam out →of a classroom, yelling, upset, seeking destruction (she is gradually calmed down); during a classroom mindful exercise at City Springs, another elementary/middle school, HLF staffer Jazmine Blackwell is confronted by an on-edge seventh grader who joins her in front of the class and won’t be quiet as Blackwell tries to take the class in the other direction through controlled breath. (Blackwell later says that part of her challenge is remaining mindful herself, that she’s guiding an entire class, not just one disrupter.) The reminders are constant, in fact: It’s not that these children are behavior problems. They are at high emotional risk.

Principal Monique Debi remembers a training session for 15 principals, just before she got the promotion to run Fort Worthington two years ago, where an HLF instructor led them through a mindful moment. She was captivated: “How do I get this for my school?” Two years ago, out of 444 students, there were 180 suspensions at Fort Worthington; this year, that number is seven. No one attributes the dramatic turnaround completely to HLF practices, but as Debi talks about her goal of building community within her school, of staff and students treating each other in a loving way, one goal in particular for students seems right up the HLF alley: “To teach them how to take care of themselves.”

“We always come back to Baltimore, to the hood, to the people we love. If you can’t do the work at home, the work is not worth doing.”

Vance Benton is in his eighth year at Patterson High School in the city’s Bayview neighborhood; Patterson has nearly 1,100 students, and Benton says it’s the most diverse high school in the state, with 40 percent of his students born outside the country. “And they are poor,” he says. “Some of them live in extreme poverty.” HLF has run its program in Patterson since 2013; Benton is a strong believer in it, and he does not mince words: “If you can control a person’s thinking, you don’t have to worry about his actions. So that’s what this is all about, to control their thinking.”

Johns Hopkins has wrapped up studying the effect of HLF initiatives, but Benton cites perhaps the most crucial help HLF can offer through a hypothetical example of two young men confronting each other on the city’s streets: “If you are challenged, and you decide to take a deep breath, and your deep breath has you pause and consider and now gives you the decision, man, it ain’t worth it—then you leave. No data in the world will show that two lives were just saved—the life that would have been taken, and the life that took the life.”

HLF’s goal now is to create a self-perpetuating model: Ali says they’re currently setting up satellite programs in South Florida and upstate New York; two senior staffers from Baltimore will live in these places for a year, serve as teachers and mentors, hire a program director, and then mindfulness will be off and running in a new place, the way to make what started with 20 kids two decades ago sustainable anywhere.

Still, the heart and soul of their work will remain in one place. “I’m certain that teaching, and coming to understand it in our bones is why, even though we have been all over the world and wined and dined and treated like royalty at times, we always come back to Baltimore, to the hood, to the people we love,” Ali says. “If you can’t do the work at home, the work is not worth doing.”

One child at a time: Long ago, Ramon Brown (above) was a troubled fifth grader in the North Smallwood neighborhood; his father had been in prison, and then murdered, and he was an extremely angry boy. Holistic Life Foundation started working with him. Now Ramon is an HLF staffer at Fort Worthington, a teacher and mentor to ten-year-old Kamaya, Jahlil, and other vulnerable children. And sometimes he thinks back to a conversation he had with Andrés González long ago: “He said, ‘You’ll always be you, no matter what. No one can change you but yourself.’ He made me think a lot about that.”

The Stress Breath Practice

By Andrés González

The kids who go through the Holistic Life Foundation Program tell me this breathing exercise stays with them throughout their lives.

The stress breath is great for any kind of stress or anxiety: test anxiety, performance anxiety, any type of anxiety at all. It’s also a good exercise for heating up your body. Here in Baltimore, some kids may not have heaters at home or proper jackets, so this is good for warming them up. With this breath, you can pull in a lot of energy and store it in your body.

Use an everyday object as a signal to do the stress breath. I use my keys. When I drive to work in the morning and take my car keys out of my ignition, that’s my cue to do the stress breath. I’ll do 12 right before I go into the office so I can leave home at home and focus on work. And then when I drive home, I park my car, take my keys out of the ignition, and that’s my cue—I do 12 more before I go into my house. That allows me to leave everything at work at work so I can be a hundred percent with my family when I get home. It’s like hitting the reset button with your brain.

The 3 Basic Elements of the Stress Breath

Fog the mirror

The most important thing about this breath is that it’s audible. Take your hand and hold it up in front of your mouth and act like it’s a mirror that you’re fogging up. So, you’re exhaling with a haaaaaaaa sound as if you’re fogging a mirror.

Make it audible

Now, do the same thing, but only have your mouth open for two seconds and then close your mouth while still pushing out the same way—but now push out through your nose. Practice making that same sound as you inhale, so the sound comes from the back of your throat (almost like a Darth Vadar breath).

Hold and lock

The HLF twist on the stress breath happens during the pause between the inhale and exhale. When you inhale, hold your breath, and then lower your chin to your chest. Hold there for a count of five and then lift your head as you exhale. Let’s put it all together…

The Stress Breath Exercise

- Inhale nice and deep, using the “fog the mirror” technique, so the sound is vibrating at the back of your throat.

- Hold your breath and your bring your chin down to your chest.

- Count back from five.

- Exhale (audibly through your nose) while you bring your head up.

- That’s one cycle. Do twelve in a row, if you can, during the day and then again at nighttime.

Why the Stress Breath Works

The reason the breath has to be audible is because the vibrations from the sound signal the vagus nerve—that connection between the mind and the body—triggering a shift in your autonomic nervous system from the sympathetic (stress response) to parasympathetic (restorative response). So, if you just walk around breathing audibly, you’re basically doing the stress breath.

How to make the practice trauma-informed: Something to remember if you’re deciding to practice this with others is to not have a silent space during the hold. That’s why we count. This is the trauma-informed way of doing the practice. You always count down (you never count up—because you don’t know when that’s going to end). And you don’t want to keep that empty space during the hold, because that’s where the trauma can pop up. You’re almost inviting the space for the stuff to pop up. We’re always doing trauma-informed when we do this with our kids.