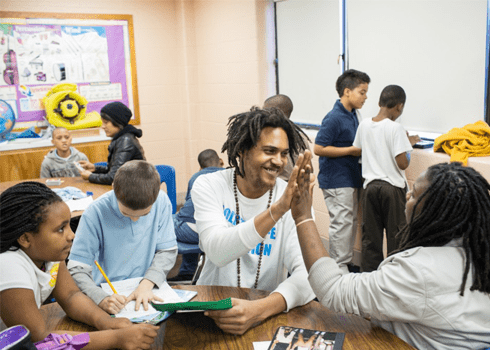

People often use the words empathy and compassion interchangeably—and certainly they share important qualities. But there is a subtle difference between empathy and compassion, and studies show that mindful attention might be key to making sure that our efforts to help are coming from a healthy, aligned place. Here’s a deeper look at how mindful qualities like present-moment attention can help us genuinely be of greater service to others, and how mindfulness can help us feel good about helping.

People naturally tend to empathize with others, report C. Daryl Cameron and Barbara Fredrickson in the January issue of the journal Mindfulness. But empathy can go wrong when it leads to distress. We might help out of guilt, obligation, or co-dependence. Or, the help might cause resentment, which could lead us to avoid helping people in the future. Or sometimes, in the absence of strong boundaries, we might unknowingly absorb the feelings of someone in trouble, and if we can’t deal with those feelings of suffering, we might turn away altogether.

There is another possible response: compassion, which leads people to try to alleviate distress in others.

The Way to Healthier Helping

As the authors speculate, “Helping should be most common among people who are able to maximize compassion while minimizing distress.” Previous research has found that cultivating mindfulness—the moment-to-moment awareness of thoughts, feelings, and surroundings—can lead to greater compassion. But what specific components of mindfulness predict real-world helping behavior? In other words, what skills could we develop that would make us more likely to help each other out?

The study examined two mindful traits—a focus on the present moment (aka, “present-focused attention”) and a non-judgmental acceptance of thoughts and experiences (“non-judgmental acceptance”). Cameron and Fredrickson assessed the mindfulness of 313 adults, asking if, for example, they “pay attention to how my emotions affect my thoughts and behaviors” or often criticize themselves “for having irrational or inappropriate emotions.”

The researchers confirmed their hypothesis: Present-focused attention and non-judgmental acceptance both predicted more helping behavior … Mindful participants were more likely to experience emotions like compassion, joy, or elevation while giving help. That could mean that they just felt better when helping others, which could lead them to engage in more helping behavior in general.

Next, the survey asked if they had recently helped someone out. If they had, participants answered questions about how they felt while helping. Did they feel positive emotions like gratitude, hopefulness, inspiration, or joy? Or did they have negative ones, like irritation, contempt, disgust, distaste, guilt, or nervousness?

In analyzing the answers, the researchers found that 85 percent of participants had engaged in some kind of helping behavior during the previous week, like listening to a friend’s problems, babysitting, giving someone a car ride, donating to charity, or volunteering. In the process, they uncovered some incidental but interesting facts:

- Men were marginally less likely than women to report engaging in helping behavior;

- Age did not predict helping; and

- Participants with higher income were more likely to report helping others.

However, the biggest predictor of helping behavior had nothing to do with these demographic traits. In fact, the researchers confirmed their hypothesis: Present-focused attention and non-judgmental acceptance both predicted more helping behavior. This link between mindfulness and helping might be traced to the fact that the mindful participants were more likely to experience emotions like compassion, joy, or elevation while giving help. That could mean that they just felt better when helping others, which could lead them to engage in more helping behavior in general.

What Makes Us Want to Keep On Helping?

The study also revealed a scientifically important nuance: Participants who scored higher in present-focused attention were more likely to experience positive emotions—and participants high in non-judgmental acceptance experienced fewer negative emotions, like stress, but weren’t necessarily more likely to experience more positive emotions. In other words, acceptance may only clear the way for helping; it’s the present-focus that could actually make the helping an emotionally rewarding experience. Together, the takeaway seems to be that approaching these situations with mindfulness helps us feel good, or at least better, about extending ourselves in service.

Insights from this study have obvious practical implications for teaching helping behavior to children. This line of research could also help people in helping professions who are at risk for burnout, or people whose mental illnesses make it hard for them to connect with others.

The study also carries hugely helpful implications for the rest of us, because anyone can feel worn down by helping other people. There’s an invitation to look at our motivations for stepping in, our boundaries and limitations and need for real rest. And there’s an opportunity to enter into opportunities for service with deeper compassionate attention and an open heart. Isn’t it nice to know there are ways we can help ourselves feel better when we do something nice for someone else?

A version of this article originally appeared on Greater Good, the online magazine of UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, one of Mindful’s partners. To view the original article, click here.

Atman Smith is cofounder of The Holistic Life Foundation, a nonprofit organization that teaches yoga and meditation to at-risk youth.