You bump into a friend on the street and you ask them what they’re up to, where they’re going, and they reply, “I don’t know. I have no idea.”

Now, you are worried. Perhaps they’re lost or aimless or ill. And after all, who wants to be aimless? Every moment in life must have purpose; every step must be in a forward direction, toward what we want or need or what is expected of us. But what if your friend’s aim is to be aimless, to have no set purpose or direction?

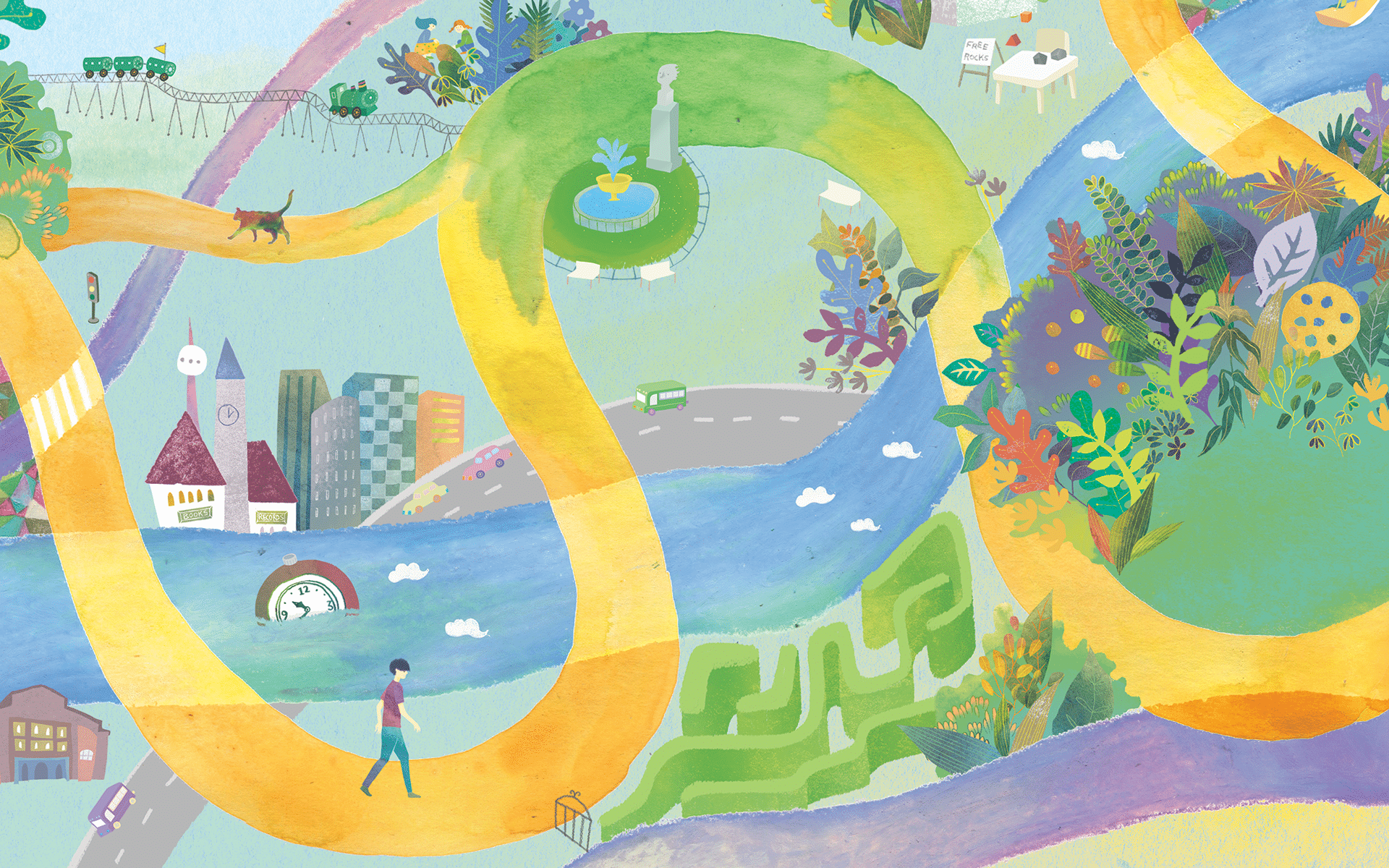

If that’s the case, they’ve become a flâneur, defined by the American Heritage Dictionary (a little harshly) as “an aimless idler,” or (more appreciatively) in the Paris Review as a “stroller, a passionate wanderer.” The poet Baudelaire praised the flâneur as someone who, by strolling about amid the kaleidoscope of daily life, finds “the timeless within the transitory.” Tied to no purpose, what passes before their eyes—and enters through their other senses—can be appreciated on the spot for simply being there.

I love to do this kind of strolling, with no aim in mind, and it never fails to yield small, and sometimes big, surprises and delights. The other day I was wandering in my neighborhood and I came upon a small table blocking the sidewalk. Behind the table was an equally small chair, and behind the chair was a path leading up a small hill through some bushes into someone’s backyard with children’s things strewn about. On the little table was a very ordinary rock, or maybe two. The young proprietor of this little stand was not there at the time, but next to the table was a multi-colored sign in chalk: Free Rocks.

That image has stuck with me now for a while. And it never fails to make me laugh, and smile in appreciation for the child who concocted the idea. When you wander, the spring you tighten inside in order to secure your purpose and direction can unwind. And that’s why “aimless wandering” has long been a mindfulness practice. It relaxes. Yes, we generally think of mindfulness as counteracting our wandering mind, and it does, but it can be larger than that. It can include the practice of just noticing one thing after another as we let ourselves out to play. We don’t have to take things too seriously. We are amused.

Here are five ways to aimlessly wander, to enjoy just being yourself wherever your feet, and your fertile brain, take you.

In the neighborhood

You don’t have to go far to wander. You can just set out from your own front door. We’ve all gone for a stroll or taken our dog for a walk. To turn it into aimless wandering involves mainly a slight shift in attitude. You commit to having no plan and importantly no set route. The highest and most enjoyable form of wandering is also as free as possible from time constraints. Of course, there’s usually someone in your life who needs you to be someplace at some point, but until that appointed time, you can wander. And if you can fit in more wandering time, so much the better. I’m not advocating exclusively wandering through life. Eventually, when we’re old enough that will become the norm, but in the meantime, it helps to have some aims in life—if only because when you go wandering, the contrast adds to the enjoyment.

At first, your mind may begin to seize on plans and looming problems to be solved. You may think if you don’t mentally address them, they won’t be taken care of, or if you think about them enough, you can make them go away. Instead, just as in a regular meditation session you would come back to your breath or the feeling of your backside on a chair or cushion, here you come back to whatever next catches your eye or ear or nose. It might even be a person. It’s fine if they engage you in a chat, but if it veers toward the serious, it may be time for you to pretend you have somewhere you absolutely must get to.

Recently, strolling in my neighborhood, my attention was drawn to the unbelievable din that comes from kids playing in a schoolyard. At the playground’s edge, I noticed two small girls huddled under a bush. They were giggling and obviously hiding from their playmates. I only eyed them long enough to take a mental snapshot, but it reminded me of how my own daughters did that decades ago and how my granddaughters do it now and how I did it as a child. And what joy there is in hiding. I saw “the timeless in the transitory.” Everything changes, but not much changes at all.

When you wander, the spring you tighten inside in order to secure your purpose and direction can unwind.

In an unfamiliar place

One of the best ways to wander is to do it in a place you’re visiting. If it’s a city you’re familiar with, it might be best to pick an area you haven’t been to yet, or at least are less familiar with. If you’re going to get off the beaten path, where tourists don’t venture, it may help you to have a local guide. They can show you things they like and answer questions you might have—so long as you enlist them in the spirit of not having too many aims.

One of the keys to wandering is to be driven by unending curiosity. Since you don’t have a plan, it’s the questions that emerge from your mind that drive you onward: “What’s that? Where does that lead? What’s that in the window?” Of course, streets with little stores can be endlessly intriguing. Old junk shops and used book and record stores—stores of all kinds can draw you in—and it’s great to go inside and browse and meet the owners and workers, but it’s good to avoid turning it into a shopping spree. Once money’s involved, things start to get a little serious.

Wandering in residential streets holds charms as well. It’s like being dropped into SimCity. You can see all the different ways we create nests and lives for ourselves, including also sadly those people whose very home is the streets. And streets also give way to parks and squares and plazas, and thankfully benches. One time in Toronto, when my feet were about to give out from beneath me, a park appeared, with plenty of benches and some very interesting winding walls and irregular mounds. As I ventured in, I noticed a bust of a man on a pedestal. As it turns out I’d wandered into Jean Sibelius Square, a tidy greenspace and playground dedicated to the Finnish composer. How odd, I thought. I was aware that Toronto is famously multicultural. My granddaughters who live there attend a school that is a virtual United Nations, and yet I was unaware of the Finnish community, who in the fifties persuaded city council to dedicate this park. I’ve since taken to listening to his dramatic tone poem Finlandia, and I am transported back to the little park.

Since you don’t have a plan, it’s the questions that emerge from your mind that drive you onward: “What’s that? Where does that lead? What’s that in the window?”

In the wild

Aimless wandering is not only about streets and cities. In fact, I’ve done considerable wandering in meadows and forests during retreats held in the countryside. In the wild, it’s important to ensure you’re not going to get lost, necessitating the formation of a search party. Wild ramblings are best done using some form of buddy system and establishing boundaries. Aimless wandering is not an extreme sport. It’s about leisure, not pushing the envelope. (That’s what base jumping and wingsuit flying are for.)

If you do it in a group, you can choose a pretty well-defined open area to let everyone roam in. (I’ve usually done it in mountain meadows, with the guideline that you may venture a little bit into the woods, but not far enough to get lost.) You choose a designated timer, and everyone surrenders anything that tells time. It’s good to choose a lengthy stretch of time, like two hours, so it’s long enough for a little boredom to set in. On the other side of boredom lies wonder and awe, but it can take a little while to sneak up on you.

As you wander, you begin to see and hear in a way we don’t usually find in everyday life, tethered as we are to our Global Positioning Systems. You start noticing, for example, that rocks are free, along with air and trees and sky. One participant in a retreat run by Janice Marturano, of the Center for Mindful Leadership, was a busy chief executive who, along with others, was discomfited when he learned he’d have to be without his phone and in silence. Walking back to his cabin, he wasn’t exactly wandering, but without his phone he was disoriented, and suddenly with the spare space left in his mind, he noticed a blanket of stars. Awestruck, he reported that he had not seen the stars in decades. For a moment, he became a flâneur.

Following the coincidences

Since becoming socialized involves fitting into all sorts of plans, routines, and schedules—from very early on our life is carved up into segments of progressive achievement, from kindergarten to PhD—we can become attached to the idea that life should follow a plan. But life is notoriously uncooperative. Sure, we have plans and some of them work out, but even when they do, it often doesn’t satisfy. So, it’s nice to have some time when we’re just guided by curiosity and coincidence.

If I’m going someplace, I usually plan out part of the trip beforehand, but I also leave time to just see what emerges, and more often than not, interesting coincidences crop up. Once I heard a snippet of a radio program with the spoken word phenom Kate Tempest, whose work modernizes ancient myths. I’d never heard of her, and suddenly she was appearing in New York on a day I was there. What serendipity! Her performance was unforgettable.

Recently I was travelling to Washington, DC, and I knew I had an afternoon free. Coincidentally, not long before, I wandered into a matinee of a movie called Cézanne and I, about the famous painter who was part of a group called “the rejects,” something I’d also never heard of. These painters, Manet and Pisarro (and Cézanne himself) among them, all went on to great fame, but all had been rejected by the Paris Salon, the group that legitimized you as a painter. Hence, “the rejects.”

It so happened that the National Gallery of Art was having an exhibition of Frédéric Bazille, a Cézanne contemporary and someone who helped give birth to impressionism. Appreciating the coincidence, I went and rediscovered the joy of this great gallery, where admission is free, and people of every different stripe from all over America and the world wander freely in an uplifting public space. I ended up there because I stumbled into a movie I’d never heard of. Having no plan can be a great plan.

On the other side of boredom lies wonder and awe, but it can take a little while to sneak up on you.

Through the ups and downs

Wandering is not necessarily all rainbows and puppies. You can also wander in and out of difficulty. A while ago, when I was making yet another trip to Toronto, I foolishly carried too much luggage all at once up some stairs (how often have I done this to avoid making another trip? Arrrgh!) I pulled a muscle in my neck, which put me in excruciating pain, particularly at night.

I asked a friend if he knew of a body worker who might be able to see me a few times in succession. He hooked me up with someone in a part of town I’d never been to. I decided to make my way there by subway, streetcar, and on foot…. It became an adventure.

After I’d been punctured with tiny needles and found some (albeit temporary) relief, I went wandering and bumped into the St. Lawrence Market, one of those great cavernous indoor markets with a hundred stalls. I’d been before, but had never approached it from this direction. I found a stall run by a Turkish man selling a cornucopia’s worth of dried fruits and nuts. His kindness and old-world charm overtook the space. Dried apricots never tasted so good, in spite of the pain slowly returning to my neck.

When bad things happen, if you can retain your curiosity, you can take them as the next turn in the road. It’s not that you are not hurt—you’re human, your heart and your body are always poised to be broken, and pain will linger. It’s just that you don’t pile up the mental pain until it’s overflowing. You keep journeying. You are resilient. You bounce back. You find the next turn in the road. Free rocks may be found there.

Go Rogue

Guidelines for Aimless Wandering

Time

If you can devote a long stretch of time, like a whole afternoon, and use the sun’s path through the sky as your timepiece, that’s great. If you have less time, set a timer. Even in airplane mode, a phone’s alarm will go off. Fitness trackers also have vibrating alarms you can use.

Destination

No set destination. When you reach crossroads and forks in the road, choose your way randomly (a mental coinflip) or follow what you’re drawn toward. In the wild, even if you are on a hiking trail you can still do a kind of wandering. It takes the form of venturing off the path a bit at points or simply stopping to admire and savor. The key is to have time and space that is not all about getting somewhere or getting something done.

Interaction

How much interaction you have is up to you. If you want it to be a completely quiet contemplative time, you can avoid getting into conversations. If bumping into people and seeing what they’re all about is part of your wandering, that’s fine too. What will defeat the spirit of wandering, though, is interacting with people at a distance, i.e., through phone calls or texts. Make your wandering a digital-free zone.

Precautions

If you are wandering in the wild, it’s not a great idea to be all by yourself (remember that guy who fell into a crack in the rocks and had to cut his arm off?). Also, educate yourself about any local dangers, such as disease-bearing ticks and excitable wild animals, and take the precautions recommended by authorities. If you’re in a complicated wild area or an unfamiliar city, be sure to have a map to save you if you truly get lost. Of course, you can rely on your GPS at that point, but a physical map is nice (yes, they still exist) because you can see the big picture better.

The flâneur himself, Barry Boyce, demonstrates the keys to aimless wandering in a short video: