The practice of mindfulness meditation promotes self-awareness and the ability to direct your attention; you can then apply the mindful attention you develop in meditation to life and leadership. The practice begins with concentration and observation. To observe is to notice and examine dispassionately—without judgment or interpretation. Observation demands a form of objectivity often associated with scientific research. Scientists studying aerodynamic phenomena, for example, engage with their object of study without regard to subjective emotions and moods; they approach their study with consistency and make detailed notes about the data they collect. The key to effective observation is detachment—a dispassionate objectivity that unlinks what is observed from meaning. Similarly, mindfulness practice requires that you become an observer of your own self. In order to develop your observer self, you learn to split your attention.

Mentally recall a meeting in which one of your colleagues was passionately promoting his point of view. Picture him leaning forward, his voice pitched in excitement, his skin flushed as he’s adamantly pressing on about his idea. Remember how you deciphered the signs of his intense commitment: voice, posture, pace, facial expression, and word choice. You observed these details and made some conclusions about his commitment, intent, and anxiety.

Great leaders are great observers. Yes, you have to articulate vision and mission and you have to effectively express goals and shape processes. But if you don’t learn to observe, you won’t fully activate all your leadership responsibilities. Strong observation skills lie at the heart of leadership abilities such as effective communication, engaging interpersonal skills, influencing people, managing change, managing group dynamics, and selling (getting buy-in) ideas, plans, and strategy. Modern leadership depends on relationships; it works in the context of rapport, bonding, and association. Meaningful relationships emerge when you know and understand the other.

Here are 5 reasons why observing others and consequently understanding them is key to your leadership effectiveness.

1. Observing and understanding others is key to relationship building.

2. Observing and understanding yourself is equally key to making better decisions and your own professional evolution. Remember: if you always do what you’ve always done, you’ll always have what you’ve always had.

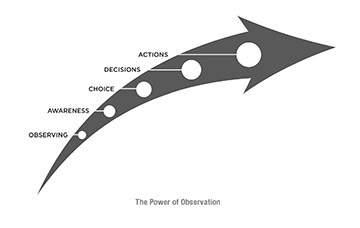

3. Observation yields awareness, awareness yields choice, choice yields expanded decisions, expanded decisions yield new possibilities for actions, and these different actions yield different results.

4. Observing and understanding others enables you to lead them effectively toward your desirable shared vision.

5. Observing and understanding yourself enables you to lead yourself toward your own desirable vision.

Developing the observer-self isn’t complicated; it starts with your choice to pay attention in a focused and dispassionate way. The easiest way to conceptualize this is by imagining a micro version of you sitting on your shoulder: It has a single task—observe and report. It pays attention to what you say, how you move, how you feel, and the effect you’re having on others. Your observer-self gathers information in real time, and as you become aware of what you are doing, you create an inventory of reality. From this inventory you can choose and select the behaviors you want to demonstrate; you may choose to conduct yourself as you have all along, but at least you’ll be doing so more consciously.

Developing the observer-self isn’t complicated; it starts with your choice to pay attention in a focused and dispassionate way. The easiest way to conceptualize this is by imagining a micro version of you sitting on your shoulder: It has a single task—observe and report.

The observer-self is an objective witness that notices, perceives, and takes in data and information; it cannot make interpretations, judgments, or changes. It is never the critic. This exercise is not intended to add self-criticism and internal disapproval. Observing and witnessing are acts of discovery, not judgment.

Fortunately, the observer-self is invisible, weightless, and doesn’t require batteries; all it requires is a portion of attention—attending to what you’re doing at the same time as you are attending to your environment. If you’ve learned to play a sport or a game, then you’ve learned how to think about what you’re doing and what others are doing, too. You learned to quickly calculate what might happen and how to prepare to respond to it. This is a skill of splitting your attention. Observing the self is directing this mental skill in a particular way.

The first leg of the journey of growth is not change; it’s awareness. Awareness, you see, changes us. Imagine the benefit of engaging in an emotionally charged debate at work and, while remaining intellectually engaged, also accessing an emotionally neutral part. How valuable would it be to analyze a mistake, for example, as you feel your passion to win, but not succumb to the frustration of losing? How might you benefit from traversing a lawsuit without letting your fear, indignation, and anger dominate?

Observation allows attention to remain open and unfettered, not caught up and lost in stimuli, and a mind prepared with observation can turn the strength of its attention to an object of concentration.

A developed observer-self heightens emotional and leadership maturity. An observer-self is not a path to becoming robotic or emotionally flat; it’s a path to wisdom that breeds better decisions and better leadership results. It’s also a partner to the concentrative ability to fix your mind on a single point. Observation allows attention to remain open and unfettered, not caught up and lost in stimuli, and a mind prepared with observation can turn the strength of its attention to an object of concentration. During concentration—as a myriad of objects and ideas try to grab center stage—observation allows them to wait their turn.