Recently I found myself in an intensive care unit at the bedside of a loved one. Of course, I was filled with strong feelings of shock, fear, and worry. But I also noticed how easily those feelings, and the thoughts accompanying them, shifted into anger. It projected itself onto anything in my field of awareness, from the staff, to the machines, to myself. I was even angry at the person in front of me who was in need of critical care.

Fortunately my loved one survived the health crisis, and in the days that followed, my experience in the ICU caused me to reflect once again on the nature of anger—to become more keenly aware of anger in myself and in others.

Anger causes so much suffering in our personal relationships and in our society. Its effects range from spats with our spouse to wars between nations. Our own anger causes suffering to others, often those we love most, and their anger causes us suffering. Anger and the wounds it causes reverberate throughout life.

In my life and in my work, I have found that there is no panacea, no instant fix, for anger. But I have learned that mindfulness can help calm the anger we feel and protect us from being hijacked into words and actions we later regret. When I was in the ICU, I felt fortunate that mindfulness training helped me recognize my anger. It allowed me to stay present with compassion for all the suffering happening there, instead of lashing out at some perceived slight or injustice. Mindfulness illuminated the thoughts of grief and vulnerability that the situation evoked in me. It helped me see that just below my anger I was gripped by fear of losing this person I loved. It was this that was fueling my anger.

What are the causes and conditions that evoke and strengthen anger? What are good ways to navigate anger as it arises? How can mindfulness and meditation practice help?

Scientists say that human beings evolved successfully in part because we have strong emotions, including so-called “negative” emotions such as anger, anxiety, and sadness. These protect us because they act as warning bells to alert us that something is wrong. They tell us we could be in danger and that we need to take action.

What we are experiencing and calling “anger” is actually a complex and unfolding series of mental and physical events designed to help us deal with a possible threat or the experience of hurt or pain. When anger arises, our instinctive response is to fight back against the threat or painful feeling, and in fact the experience of anger is constructed to help us do that. Specifically, most emotion researchers agree that anger is made up of a fight-or-flight reaction in mind and body, plus an insistent inner narrative of thoughts and beliefs about what has happened or might happen next.

Anger is Not Solid

Have you ever been watering your grass and suddenly noticed a beautiful expression of light and color appear in the stream of your garden hose? We call this a rainbow, but actually that’s only a name for something that arises from many non-rainbow elements. It takes sunlight, water, and other conditions to come together in a moment for the experience we call rainbow to appear. And when one or more conditions change, the rainbow disappears.

Anger is like that. It is made of non-anger elements. Practicing mindfulness helps you see those elements and guide you to make choices about how to relate to them.

For example, if you become mindful that anger is arising in you, you could choose to breathe mindfully and step back from it.

Or you could choose to look into it more deeply. Without judging yourself, you could simply inquire, “What are the feelings and thoughts present in this moment?”

Or, being mindful that anger is in you, you could recognize it as the momentary experience of suffering and touch it—and yourself—with compassion and kindness.

Anger, like everything else, happens in the present moment. The conditions that come together to form an experience of anger appear, change, and depart moment by moment. Becoming more mindful helps you stay in the present moment, observing how anger arises and subsides on the spot. This makes you less vulnerable to hijacking by anger—and wiser, too.

Working with anger can be as simple (but not always easy!) as becoming more mindful of anger when it arises in the present moment. Here are some practice-based ways to help you do that.

Stopping to See Your Anger

We can get caught in a storm of anger over just about anything. Then it is a big challenge to step back and disentangle ourselves from the surging current of heated emotions, intense bodily sensations, and harsh thoughts carrying us forward.

Because of your natural mindfulness, there will eventually come a moment when you recognize that you are caught in angry feelings. In that instant of awareness, knowing how to stop and disentangle from the ongoing angry reactions in mind and body is critical.

There are many effective ways, based in mindfulness, compassion, and wisdom, to stop being swept away by anger. Here is one you could experiment with.

Practice: Name the Feeling

Noticing you are feeling angry or annoyed, pause and take a few mindful breaths. Gently place attention on your body and the sensations of breathing or, if it helps, deliberately take a few deeper breaths. Remain present and carefully notice the changing sensations of each in-breath and each out-breath.

Name the feeling you are experiencing: “This is anger.” Just notice. You don’t have to get rid of it. Breathing mindfully, whisper the name a few more times. What do you notice now?

Understanding Your Anger

As we learn more effective ways to stop and step out of intense feelings of anger, we immediately empower ourselves to look a bit closer at the causes and conditions that are creating and sustaining our feelings of anger and aversion.

Once on a meditation retreat, I experienced a period of practice filled with such intense anger and violent images they actually frightened me. When I asked the teacher for help, he told me to look more deeply. “Beneath anger is fear,” he said. “Beneath fear is a fixed belief. What is the belief that is driving your fear and anger?”

An approach recommended by therapists and mindfulness teachers alike is to ask ourselves if the frightening belief underlying our anger and fear is actually true. It is helpful to ask ourselves, “Am I in danger in this moment? Why? How?”

I call this analysis the “structure of anger,” and I have found it a very useful approach to understanding the causes and conditions supporting and sustaining anger in me. Interestingly, the approach works equally well for anger at a horrific external event such as the Boston Marathon bombings, or for an irritating encounter with a stranger on the street. All that’s required is to stop and look at the feeling deeply and mindfully, inquiring and listening with a spirit of curiosity.

Here is a meditation practice you could use to understand the structure of anger.

Practice: What is Making Me Angry

When you notice anger, irritation, or stronger feelings such as rage or hatred arising in you, stop and take some time to be more mindful of them.

Apply steady attention on your body by feeling the shifting sensations as you move or the subtler interior ones if you are sitting still. Resting your attention on your breathing, take a few mindful breaths, noticing the different sensations as the in-breath and the out-breath come and go in various places in your body.

You don’t have to do anything special. Just relax and trust your awareness to notice. Allow yourself to rest in that awareness.

When attention steadies and you can feel the sensations of your body or your breath more clearly, ask some simple questions while resting in awareness: What is upsetting about this situation? What am I thinking that is worrying or frightening me? What is making me angry, sad, or disappointed right now?

Practice without judging yourself or needing to fix anything. Breathing with awareness, offer your mindful questions with a spirit of curiosity, listening gently for any response that your natural intelligence and wisdom produces in response to your questions.

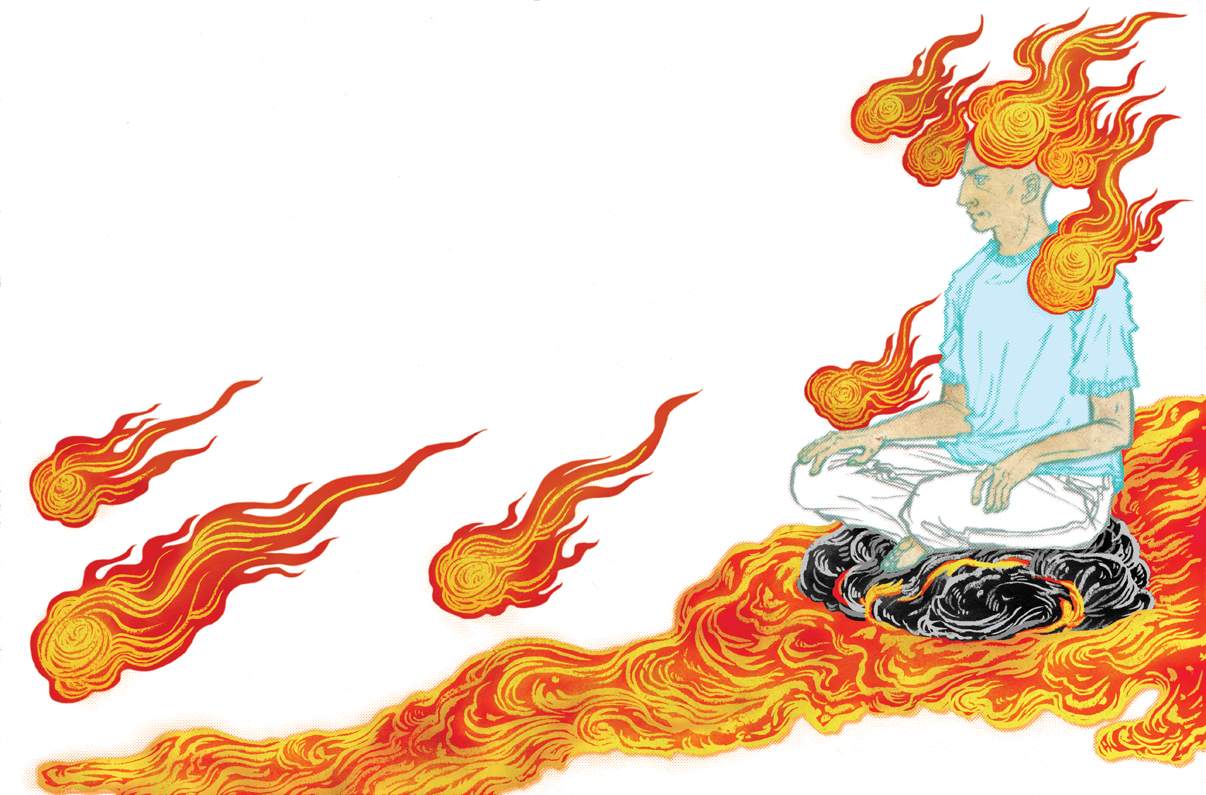

Befriending Your Anger

Anger is an expression of aversion to and rejection of the reality unfolding in the present moment. Interestingly, when you look more deeply inside yourself, you may find that other feelings, such as irritation, annoyance, resentment, and boredom, can also be expressions of dislike and rejection for what is happening now.

It is helpful to bring mindfulness to any of these feelings of disliking or rejecting when they arise. You might decide to focus mindfully on a particular expression of aversion. For example, you might decide: “Today I am being mindful of boredom when it is in me.”

It is equally important to notice your feelings about having angry, rejecting feelings. Do you feel angry at being annoyed, or bored? Are you angry at feeling angry?

Besides sharing a common feeling of dislike and rejection of some aspect of the present moment, the other thing that anger, scorn, irritation, boredom, and their like share is that when they arise, we suffer.

When you recognize that suffering is present when you feel anger and aversion, you can choose kindness and compassion instead of self-criticism and dislike for your experience. Here is a brief practice you can use to explore being more compassionate when the pain of anger visits you.

Practice: Offering Compassion

When you notice feelings of anger or aversion inside, pause and breathe mindfully. Name the feeling: “Anger is here now.” “Boredom is here now.” Let it be and look deeply.

Breathing mindfully, name it also as suffering: “This is the feeling of suffering.” “Suffering is here now.”

As much as feels safe to you, allow yourself to soften into this moment. Breathing mindfully, trust your capacity to hold the suffering of anger and ill will, and yourself, compassionately and in awareness. Do this the same way you would be present and extend compassion to a loved one in pain.

Offer yourself compassion with a phrase, quietly whispering it as you breathe: “May I be safe and protected.” “May I be at ease.” “May this situation teach me about the true nature of life.” Listen deeply to any response that follows. Let your intelligence and goodness of heart guide you forward.

Anger, ill will, scorn, and other dismissing, rejecting emotions are part of our lot as human beings. We are not failures because we experience these intense feelings. It is how we respond when they arise in us that makes all the difference. Anger and ill will are teachers and opportunities for insight and growth. Meeting these emotions with mindfulness and compassion can guide you to the lessons they have to offer—and help you find peace amid all of life’s difficulties.