We all get lost in the dense forest of our lives, entangled in incessant worry and planning, in judgments of others, and in our busy striving to meet demands and solve problems. When we’re caught in that thicket, it’s easy to lose sight of what matters most. We forget how much we long to be kind and openhearted. We forget our ties to this sacred earth and to all living beings. And in a deep way, we forget who we are.

My dense forest hums with a background mantra: There’s not enough time. I know I’m not alone; many of us speed through the day, anxiously crossing tasks off the list. This often comes hand in hand with feeling beleaguered, annoyed at interruptions, and worried about what’s around the corner.

My anxiety escalates when I’m preparing for an upcoming teaching event. I remember an afternoon some years ago when I was in last-minute mode. I was madly searching through my very disorganized electronic files, trying to find material for a talk I’d be giving that evening on loving-kindness. Much like the files, my mind was stirred up and muddy. At one point, my 83-year-old mother, who had come to live with my husband, Jonathan, and me, popped into my office. She started to tell me about an article she liked from The New Yorker. But seeing me glued to the computer screen (and probably frowning), she quietly placed the magazine on my desk and left. As I turned to watch her retreat, something in me just stopped. She often came by for a casual chat, and now I was struck by the reality that she wouldn’t always be around for these companionable moments. And then I was struck again: Here I was, ignoring my mom and mentally scurrying around to compose a talk on love!

When we’re caught in that thicket, it’s easy to lose sight of what matters most. We forget how much we long to be kind and openhearted.

This wasn’t the first time I was jarred by forgetting what mattered. During that first year my mom lived with us, I repeatedly felt squeezed by the additional demands on my time. Often when we had dinner together, I’d be looking for the break in the conversation when I could excuse myself and get back to work. Or we’d be on errands or going to one of her doctor’s appointments, and rather than enjoying her company, I’d be fixated on how quickly we could get everything done. Our time together often felt obligatory: She was lonely and I was the main person around. While she didn’t guilt-trip me—she was grateful for whatever time I offered—I felt guilty. And then when I’d slow down some, I also felt deep sadness.

That afternoon in my office, I decided to take a time-out and call on RAIN to help me deal with my anxiety about being prepared. I left my desk, went to a comfortable chair, and took a few moments to settle myself before beginning.

The first step was simply to Recognize (R) what was going on inside me—the circling of anxious thoughts and guilty feelings.

The second step was to Allow (A) what was happening by breathing and letting be. Even though I didn’t like what I was feeling, my intention was not to fix or change anything and, just as important, not to judge myself for feeling anxious or guilty.

Allowing made it possible to collect and deepen my attention before starting the third step: to Investigate (I) what felt most difficult. Now, with interest, I directed my attention to the feelings of anxiety in my body—physical tightness, pulling and pressure around my heart. I asked the anxious part of me what it was believing, and the answer was deeply familiar: It believed I was going to fail. If I didn’t have every teaching and story fleshed out in advance, I’d do a bad job and let people down. But that same anxiety made me unavailable to my mother, so I was also failing someone I loved dearly. As I became conscious of these pulls of guilt and fear, I continued to investigate, contacting that torn, anxious part of myself. I asked, “What do you most need right now?” I could immediately sense that it needed care and reassurance that I was not going to fail in any real way. It needed to trust that the teachings would flow through me, and to trust the love that flows between my mother and me.

I’d arrived at the fourth step of RAIN, Nurture (N), and I sent a gentle message inward, directly to that anxious part: “It’s okay, sweetheart. You’ll be all right; we’ve been through this so many times before…trying to come through on all fronts.” I could feel a warm, comforting energy spreading through my body. Then there was a distinct shift: My heart softened a bit, my shoulders relaxed, and my mind felt more clear and open.

I sat still for another minute or two and let myself rest in this clearing, rather than quickly jumping back into work.

The Benefits of RAIN

My pause for RAIN took only a few minutes, but it made a big difference. When I returned to my desk, I was no longer caught inside the story line that something bad was around the corner. Now that I wasn’t tight with anxiety, my thoughts and notes began to flow, and I remembered a story that was perfect for the talk. Pausing for RAIN had enabled me to reengage with the clarity and openheartedness that I hoped to talk about that evening. And later that afternoon, my mom and I took a short, sweet walk in the woods, arms linked.

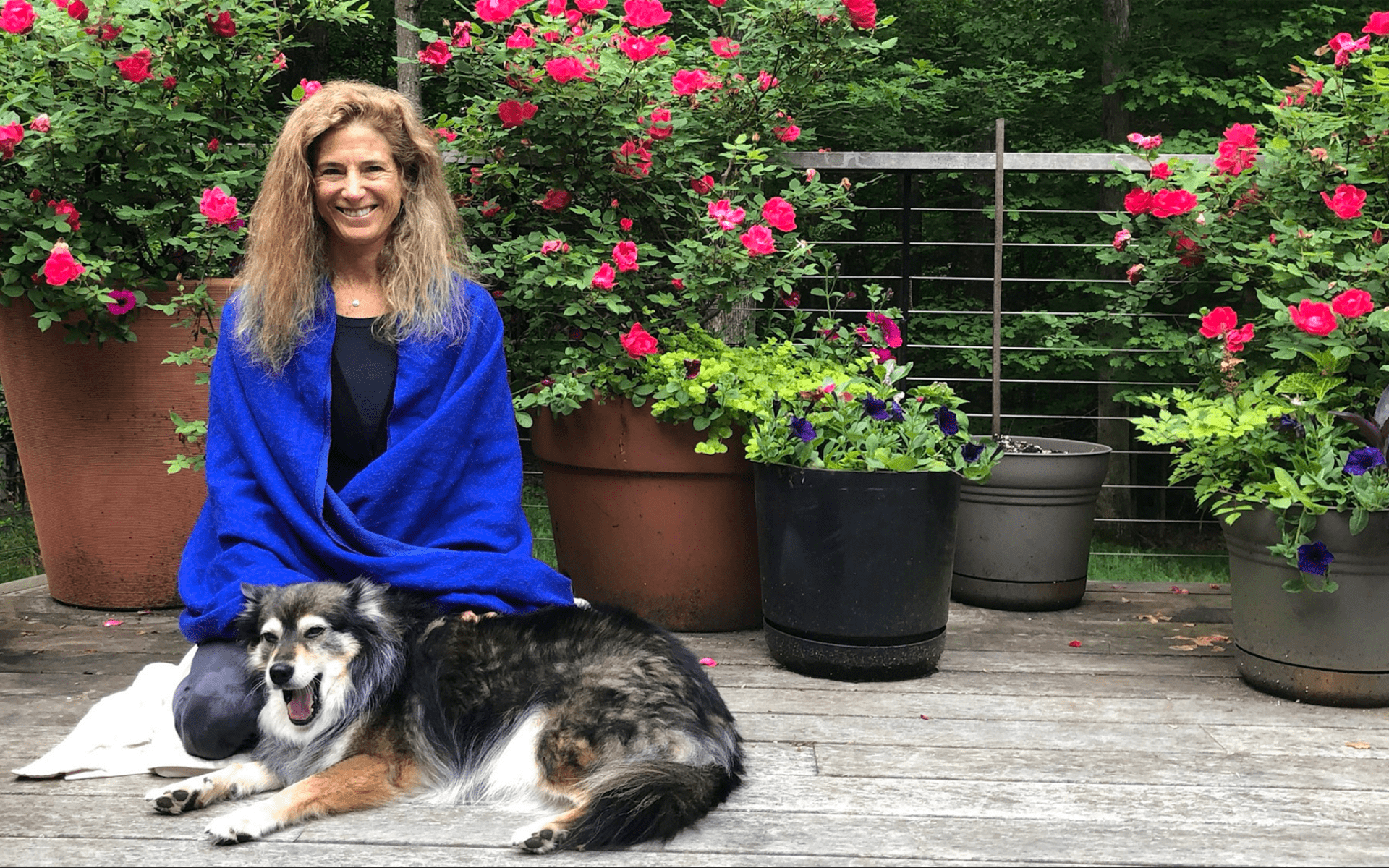

Since then, I’ve done a brief version of RAIN with anxiety countless times. My anxiety hasn’t gone away, but something fundamental has changed. The anxiety doesn’t take over. I don’t get lost in the dense forest of trance. Instead, when I pause and then shift my attention from my story about getting things done to my actual experience in my body and heart, there’s a spontaneous shift to increased presence and kindness. Often I’ll keep working, but sometimes I decide to change gears, to step outside and play with my pup, make some tea, or water the plants. There’s more choice.

Four years after moving in with Jonathan and me, my mother was diagnosed with lung cancer. One afternoon about three weeks before her death, I sat by her bedside reading from a book of short stories we both love. She fell asleep as I was reading, and I sat there watching her resting easily. After some minutes, she woke up and mumbled, “Oh, I thought you’d be gone; you have so much to do.” I leaned over, kissed her cheek, and continued to sit with her. She fell back to sleep, a slight smile on her lips.

I did have a lot to do. I always have a lot to do. I flashed on being too busy to pause and talk about that New Yorker article, and all those times I’d rushed through our shared dinners, felt dutiful about spending time together and guilty when I saw her walking outside alone. But my practice of RAIN had changed something. In our final years together, I was able to pause and really be there. I was there for making our supersized salads, for walking our dogs by the river, for watching the news, for chatting long after we’d finished a meal.

Twenty minutes later, my mother woke up again and whispered, “You’re still here.” I took her hand and she soon drifted off. I began crying silently, and something in her was attuned because she squeezed my hand. Oh, I’d miss her terribly. But my tears were also tears of gratitude for all the moments we lived together. And for the clearings that made this possible. On the day of her death, I was filled with immense sorrow and love, but no regrets.

Practice the RAIN Meditation with Tara Brach

Practice the RAIN Meditation with Tara Brach

Sitting quietly, close your eyes and take a few full breaths. Bring to mind a current situation in which you feel stuck, one that elicits a difficult reaction, such as anger or fear, shame or hopelessness. It may be a conflict with a family member, a chronic sickness, a failure at work, the pain of an addiction, a conversation you now regret. Take some moments to enter the experience—visualizing the scene or situation, remembering the words spoken, sensing the most distressing moments.

R—Recognize What Is Happening

As you reflect on the situation, ask yourself, “What is happening inside me right now?” What sensations are you most aware of? What emotions? Is your mind filled with churning thoughts? Take a moment to become aware of whatever is predominant, or the overall emotional tone of the situation.

A—Allow Life to Be Just as It Is

Send a message to your heart to “let be” this entire experience. Find in yourself the willingness to pause and accept that in these moments, “what is…is.” You can experiment with mentally whispering words like “yes,” “I consent,” or “let be.”

You might find yourself saying yes to a huge inner “no,” to a body and mind painfully contracted in resistance. You might be saying yes to the part of you that is saying, “I hate this!” That’s a natural part of the process. At this point in RAIN, you are simply noticing what is true and intending not to judge, push away, or control anything you find.

I—Investigate with a Gentle, Curious Attention

Bring an interested and kind attention to your experience. Some of the following questions may be helpful. Feel free to experiment with them, varying the sequence and content.

What is the worst part of this; what most wants my attention?

What is the most difficult/painful thing I am believing?

What emotions does this bring up (fear, anger, grief)?

Where are my feelings about this strongest in my body?

When I assume the facial expression and body posture that best reflect these feelings and emotions, what do I notice?

Are these feelings familiar, something I’ve experienced earlier in my life?

If the most vulnerable, hurting part of me could communicate, what would it express (words, feelings, images)?

How does this part want me to be with it?

What does this part most need (from me or from some larger source of love and wisdom)?

A final note: Many students initially see “Investigate” as an invitation to fire up their cognitive skills—analyzing the situation or themselves, identifying the many possible roots of their suffering. While mental exploration may enhance our understanding, opening to our embodied experience is the gateway to healing and freedom. Instead of thinking about what’s going on, keep bringing your attention to your body, directly contacting the felt sense and sensations of your most vulnerable place. Once you are fully present, listen for what this place truly needs to begin healing.

N—Nurture with Loving Presence

As you sense what is needed, what is your natural response? Calling on the most wise and compassionate part of your being, you might offer yourself a loving message or send a tender embrace inward. You might gently place your hand on your heart. You might visualize a young part of you surrounded in soft, luminous light. You might imagine someone you trust—a parent or pet, a teacher or spiritual figure—holding you with love. Feel free to experiment with ways of befriending your inner life—whether through words or touch, images or energy. Discover what best allows you to feel nurturing, what best allows the part of you that is most vulnerable to feel loved, seen, and/or safe. Spend as much time as you need, offering care inwardly and letting it be received.

How RAIN Began

by Victoria Dawson

Insight meditation teacher Michele McDonald introduced the RAIN practice about 20 years ago, as a way to expand the common view that mindfulness is simply a synonym for paying attention. In identifying the qualities of attention that make up a complete moment of mindfulness, McDonald, who is cofounder of Vipassana Hawaii, coined the acronym RAIN for Recognition of what is going on; Acceptance of the experience, just as it is; Interest in what is happening; and Non-Identification to depersonalize the experience. Over the years, Tara Brach modified and popularized RAIN, shifting the “N” step to Nurture and suggesting non-identification as a product of her revised four steps.

Read More

Tara Brach on The Transformative Power of Radical Compassion

Psychologist and longtime meditation teacher Tara Brach discusses why self-compassion is more essential for our well-being than ever.

Read More